Meera M. Panicker offers us a glimpse into Kadar ways of life, and how their everyday practices and their battles for forest rights serve as a lesson in Kerala’s current moment of environmental crisis.

Meera M. Panicker

A Short Walk

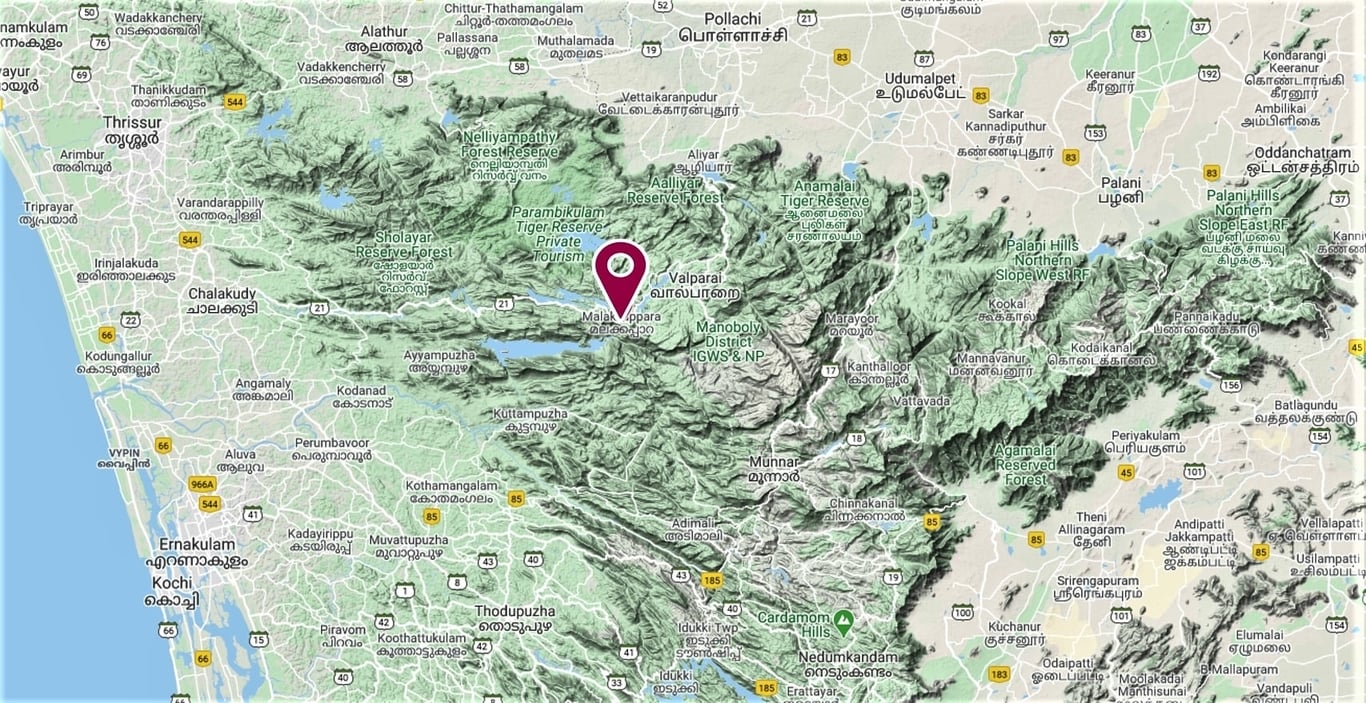

Soundarya and Chandralekha, two young Kadar women, walked ahead leading the way while Indraniyamma accompanied my field companion and me to the river. Jackie and Julie, the two dogs, trudged along with the small group of women. Dogs have always been an integral part of Kadar life. We had decided to go to the river for a dip. The walk to the river would have taken five minutes for the three Kadar women, but it took fifteen minutes today because of the two pairs of inexperienced feet. We had started from their home at the edge of the Malakkappara ooru (hamlet) from where you could see the seventy-odd houses of the settlement. It was a beautiful place nestled in the Anamalai hills, 60 kilometres from the Athirappilly waterfalls on the Chalakudy river.

‘These are arrowroot plants growing here and that is turmeric over there’, Indraniyamma explained to us while plucking away a few. She showed the yellow insides of the turmeric for our sake and threw away the rest. My field companion was a botanist interested in the reservoir of knowledge about the forest ecosystem in Kadar culture. So, the three women would stop at every plant they knew to explain their names and uses. There were edible tubers of various kinds as well as medicinal plants for stomach ailments and wounds. Indraniyamma did not forget to point out the white dammer trees and black dammer trees that my companion was particularly interested in. She pointed out the ridges in their trunks where someone from the village had made cuts to collect resin. She explained the long and arduous process of extracting the resin from the black dammer trees: one had to cut a ridge on the tree and wait for some time before making a fresh cut on the same tree, waiting for the resin to bleed and harden. They also had to make sure that multiple people did not cut from the same tree for that would lead to the death of the tree. It was getting harder to get black dammer and white dammer resin because there are fewer trees in the forest and demand was getting higher.

‘That is fresh elephant dung there!’ I was alarmed. ‘It’s okay, that is from yesterday night when the elephants came to the settlement.’ Indraniyamma assuaged my fears. Elephants had been coming to the settlement more frequently. Earlier, they used to come in the summers, but the visits have increased over the last years, as has the destruction. But Indraniyamma was not complaining. She agreed with the mooppan (village headman) that the elephants were only coming there because of their helplessness. The Kadar see elephants and other animals of the forest as one among them. They identify with the wild animals more than they do with the nattukaar (people of the country, outsiders). Our short walk had come to an end as we reached our destination, the river where Kadar women came to bathe and fish for their everyday needs.

‘We are the Forest, the Forest is Us’

I relate this small anecdote to impress upon you the knowledge and ecological sense of the Kadar community. The Kadar are a small hyper-endemic tribe (their total population in Kerala is 1,974) who reside in the Anamalai hills of Kerala and Tamil Nadu. One of the few remaining hunter-gatherer tribes of South India, they are one among the 75 Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTG) in India and one among the only five in Kerala. Kadar match all the three criteria listed by the Dhebar Commission for the inclusion of a tribe in the PVTG list: i) they live in a pre-agricultural system of existence, ii) they have zero or negative population growth, and iii) they have an extremely low literacy level in comparison with other tribal groups. First mentioned in Edward Thursten’s Castes and Tribes of Southern India (vol.3) published in 1909, the Kadar have been a much-studied tribal group. Thursten described Kadar as a quasi-nomadic tribe who spend weeks and months in the forest—their prime source of nutrition and livelihood. 81.19 percent Kadar depend on forest-based activities, and on non-timber forest produce or Minor Forest Produce (MFP) from the wet evergreen forests of the Anamalais (Scheduled Tribe Development Department 2013).

There is a lot to be written about the Kadar community and their culture but I will restrict myself here to writing about their practices of forest management and conservation, and how this ties to their identity. These inferences are based on my observations and field interviews with members of the community taken for my MA dissertation as well as from conversations with Dr K. H. Amitha Bachan of the Western Ghats Hornbill Foundation, where I worked as a research intern.

I spent seven days in the village of Malakkappara for my fieldwork in March of 2019 where I spent most of my time with the women of the tribe. I also spent a few days birding with friends from Malakkappara. Journeying with them through the forests of Anamalai hills was an eye-opening experience. They knew every nook and cranny of the forest; especially the older generation who went to the forest to collect honey and other MFP. While Kadar men collect honey from the high trees of the rainforest and the cliffs on the riverside, Kadar women assist them in the collection of stingless bees’ honey and tubers. They go into the forest for weeks, living in small temporary sheds, accompanied by their faithful companions—their pet dogs—and sustaining themselves on what little they could carry and with what they gathered from their surroundings. While accompanying them on their trips, I continued to be surprised by their knowledge of the terrain. Watching the 60-year-old mooppan climb up steep slopes in seconds while I floundered for footing and fell multiple times was hilarious for them and revelatory for me.

In my conversations with Dr Bachan, he impressed upon me how the Kadar live sustainably as part of the ecosystem—’becoming a niche’ in the ecosystem, to use an ecological term. 1 The Kadar have traditional protocols to ensure the sustainable use of forest resources. Extraction of resources becomes unsustainable and exploitative when it does not ensure regeneration. And this is a principle well inculcated in the ecological sense of Kadars developed over the centuries of their relationship with nature. Every practice of resource collection—be it honey, firewood, resin, or herbs—is designed to allow time for regeneration.

A small number of Kadar used to take hornbill chicks from nests when times were dire, which was not a problem when hornbills were abundant in the hills. However, by 2001, this became an unknowingly dangerous practice when 54 percent of the natural forest was felled by plantation owners and the state for teak and tea plantations (George 2001), dwindling hornbill populations and inducing more scarcity for the Kadar. With the Western Ghats Hornbill Foundation’s (WGHF) awareness programmes, this practice of taking hornbill chicks has nearly become non-existent with only one case reported in the last ten years (Bachan et al. 2013). They have also stopped the over-extraction of resin from black dammer and white dammer trees, by ensuring that no more than one person extracts from a tree, after the efforts of WGHF and the Forest Department. This shows an openness to change when they see that their traditional practices need to be transformed for the sustainability of the forests.

Kadar’s ecological sense should be understood in tandem with their own sense of identity. The two are tied together and one gives meaning to the other. They are dependent on the forest for their sustenance, but beyond this relationship of dependence, the Kadar have a more simple but layered relationship with nature. Their lives are tied to the forest, not just ecologically but also culturally. They are an animistic group, and their most important idol is the Karimala Gopuram, which they worship. The Karimala Gopuram is a mountain in the Anamalais, and their myths and mores exist intertwined with Karimala and the surrounding mountains (Divya 2014). They show aversion to moving beyond the surroundings of this landscape to which their histories and their present are tied. Their notions of identity are even more interesting. They identify with the animals in the forest, describing how, like the elephant and the wild gaur, they too are nomads in the forest. Much like the elephant and the wild gaur, Kadar never mark their routes in the forest, and they never forget their routes either (Divya 2014). Their myths, mores, and principles make Kadar form a collective identity with nature. Kadar have a symbiotic relationship with nature and they believe in the coexistence of Kadar and kaadu (forest). In an interview with Soundararajan, a Kadar man from Malakkappara, I asked what forest conservation practices they practice, like bans on certain kinds of resource extraction. Taking great offence, he replied, ‘Kaadaanu kaadar, kaadaraanu kaadu’. 2 Roughly translated as ‘the forest is us, and we are the forest’, this is a statement that succinctly portrays the weaved identity of Kadar and the forests. He was affronted because I had assumed that they harm the forests with their resource collection practices, while they firmly believe that they are part of it and will not do anything to harm it.

Changing Times, Unchanging Battles

The times have changed, and so have the Kadar. Acculturation has led to significant erosion in the knowledge of Kadar youth. Only a few older women and men remember the stories and songs of the olden times. They are trying to enter the market for jobs although it is not easy, considering their low literacy rates. Reduction in forest cover due to deforestation, hydroelectric projects, and other anthropogenic activities, as well as restrictions of access to forests, have made it unsustainable for them to depend entirely on forests for livelihood and sustenance. Many work as daily-wage labourers or forest guards in order to get two square meals a day. The younger generation now grows up away from the settlement, in Model Tribal Schools and hostels around Thrissur and Palakkad. However, as my anecdote earlier shows, they still retain their know-how about the terrain and the ecosystem—knowledge that few outsiders and environmentalists have. Soundarya and Chandralekha would time and again point out herbs and plants to me, listing out their medicinal values.

It is this enduring ecological identity that galvanised the Kadar to organise against the proposed Athirappilly Hydroelectric Project and successfully defeat it using their fundamental rights and forest rights. As inspiring as the Dongria Kondh of Niyamgiri, the Kadar used the Forest Rights Act 2006 to pass resolutions against the project at the Grama Sabha level, and finally succeeded in making the government shelve the project.

Kerala’s famed “development model” has never had space for tribes. The literacy rate among tribal communities remains low, and infant and maternal mortality rates are high. Poverty is rampant and malnutrition a regular feature among children and adults. The much-touted “participatory development model” of Kerala has willfully ignored the voices of tribes. This becomes viscerally evident when one listens to the stories of displacement from the Parambikkulam valley and the banks of the Chalakudy river. The Malakkappara Kadar have been relocated not once or twice, but thrice in their lifetime.3 A quasi-nomadic group, they were pushed to settle in Chandanthode, and then had to relocate because of the Sholayar Hydroelectric Project, and once again, when more dams were constructed on the Chalakudy river. They were not only displaced but their livelihood destroyed because of the submergence of the forest they depended on.

It is the anger and resentment from this, along with the realisation that their forests were being destroyed, that fuelled their fight against the Athirappilly project. The development required by the majority of Kerala is usually at loggerheads with the development that is favoured by the tribes. The Kerala model has not reached the settlements in the Anamalais although it is the waters of the Anamalais that light up the state. Today, the Kadar work together with groups like the WGHF and the Forest Department to protect the forests. They are armed with their knowledge of the forests and the rights conferred to them by the constitution through FRA, 2006 (although that too, is being watered down by the central government). We, the naattukaar, as Kadar refer to us, need to introspect about our development models that supposedly aim at sustainable and inclusive development but in reality, only prioritise the needs of the middle and upper classes, excluding tribal voices altogether. It took 162 days of nilpu samaram (standing protest) for the Kerala government to take cognizance of the demands of the Adivasi Gotra Maha Sabha to implement the Panchayats (Extension to the Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996 (PESA) (Times of India 2014). The Kadar waged a battle spanning three decades to bring to an end the Athirappilly project. It is important in this time of climate crisis, where we are seeing multiple destructive deluges, to take cognizance of our fragile ecosystem and incorporate the ecological notion that tribes like Kadar have into the development models that we tout.

References

- Bachan, Amitha K. H., Ragupathy Kannan, S. Muraleedharan and Shenthil Kumar. 2013. Participatory Conservation and Monitoring of Great Hornbills and Malabar Pied Hornbills with the involvement of endemic Kadar Tribe in the Anamalai hills of Southern Western Ghats, India. Raffles Bulletin of Zoology, supplement 24 (2013): 37–43.

- Divya, K. 2014. Tribal Culture, State and Forest Conservation: A Case Study of the Kadar Tribe, Kerala. Unpublished MPhil dissertation. Mumbai: Tata Institute of Social Sciences Mumbai.

- Scheduled Tribes Development Department, G. of K. 2013. ‘Scheduled Tribes of Kerala: Report on the Socio-economic Status’. Thiruvananthapuram: Government of Kerala.

- George, Sunny. 2001. Assessment of the Impact of Man-Made Modifications on the Chalakkudy River System in Order To Develop an Integrated Action Plan for Sustainable River Management. (September 1999 – February 2001)

- Thursten, Edgar. 1909. Castes and Tribes of Southern India. Vol.3. Madras: Government Press.

- Times of India. 2014. Nilpu samaram called off after 162 days: Thiruvananthapuram News. Times of India, 14 December 2014. Retrieved from https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/thiruvananthapuram/Nilpu-samaram-called-off-after-162-days/articleshow/45559934.cms

About the Author: Meera M. Panicker has an M.A. in Development Studies from IIT Madras.

One comment