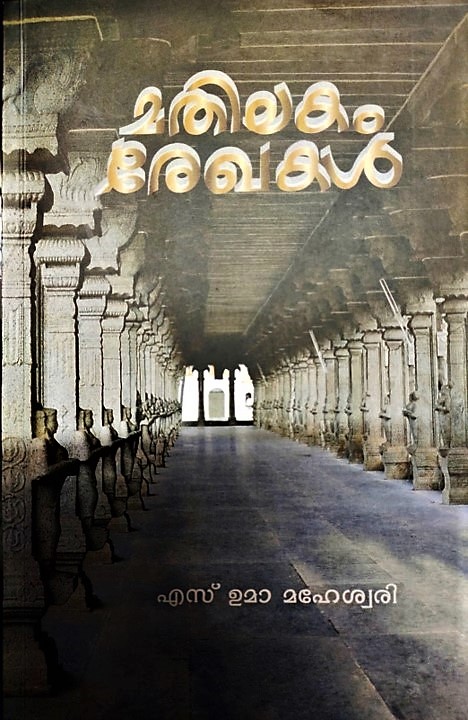

Drawing our attention to a largely unexplored and incredibly vast archive of Travancorean history, Dr. Vysakh A. S. presents a few intriguing snippets from S. Uma Maheswari’s eponymous book on the archive, Mathilakom Records.

Vysakh A. S.

The Mathilakom Rekhakal (Mathilakom Records) authored by S. Uma Maheswari delves into innumerable incidents of Travancore’s history hidden away in a few palm leaf manuscripts, identified as the Mathilakom Records, of the erstwhile princely state of Travancore. These records had held no one’s attention until now, and Maheswari’s valuable book provides the general reader with a tantalizing glimpse into this vast archive.

Mathilakom Records are documents written on cadjan (palm) leaves, pertaining exclusively to the Sree Padmanabhaswami Temple and the Venad/Travancore region. As these documents were stored inside the temple, also called mathilakam, they were christened ‘Mathilakam Records’. The Venad Ruler had entrusted three teams of men to prepare these documents, granting them hereditary rights to engage in this activity. One team prepared the Rajyakaryam—the day-to-day happenings in the kingdom, while another documented the daily happenings in the temple, and the third one focused on recording revenues. These cadjan records were shelved as bundles. Each bundle is called churuna and each leaf ola. One churuna is a bundle of a thousand olas, and there are 3000 churunas (30 lakh cadjan leaves) in the possession of the Central Archives in Thiruvananthapuram. It is unknown as to which of the Travancore rulers initiated this practice, but it continued unhindered until 1882, when the then Maharaja Vishakam Tirunal issued orders to switch over to paper, after which records were maintained as printed manuscripts. As part of this transition, the Mathilakom Records were transcribed as well. Uma Maheswari observes:

‘…in 1937, Mahakavi Ulloor Paameswara Iyer, Sadasyatilakan T. K. Velupillai, and Sooranadu Kunjan Pillai, assisted by nearly 30 scribes, attempted to transcribe the cadjan records on to paper registers. In three years, they could prepare 205 volumes of registers with an average of 500 pages in each register. This forms only five per cent of the main source. It is obvious that one lifetime is not enough even to have a cursory look at the Mathilakam Records. In 1941, Mahakavi Ulloor brought out a book titled Important Mathilakam Records. The book carried a reproduction of selected 250 records with a very brief summary in English. That has been the main source for historians‘.1 (Maheswari 2018, 12)

Here, I present five intriguing vignettes from the Records, as presented in Uma Maheswari’s book.

The Mukkuvas and the State

This year, Kerala witnessed devastating floods and denudation for the second consecutive year, and once again, the ‘sons of the sea’ were the first to come to the aid of the affected population. During the floods of August 2018, the fishermen, traditionally called the mukkuvas, made an indelible mark through their selfless service. As a sign of indebtedness to their noble service during the 2018 floods, the present Travancore royal family had honoured them.

However, the 2018 floods in Kerala was not the first time that the mukkuvas had provided deployed their service to the State. The Mathilakom records provide an insight into the role of mukkuvas in the service of the Maharaja and the State in Travancore’s history. During the customary aaratt (procession) of Lord Padmanabha which the ruler himself leads, ablutions of the idols of the Lords are performed in the Arabian sea at Sanghumukham. The mukkuvas are entitled to safeguard the ruler and the ceremony by forming a security belt encircling the seashore even at present. This responsibility was bestowed upon the Valia Veettarayan and the Cheriya Veettarayan, representatives from the mukkuva community (churuna 2308, ola 66, Kollam Era 966). Their services were also sought in certain strategic tasks such as transporting the firearms, massive cannons and other artillery through the sea from Valiathura, Anjengo etc. (138).

The Kingless Kingdom

Travancore had no ruler for 130 days after the demise of Avittam Tirunal Rama Varma in 986 ME (Malayalam Era) (1811-1812 AD), when there occurred an unprecedented tug of war for rule led by Visakham Tirunal Kerala Varma, backed by the Udiyeri Nambuthiris. Kerala Varma was the son of Attam Tirunal Bhageerathi of Chenga Kovilakam, from where the Kartika Tirunal Maharaja had adopted two princesses to Travancore family. Kerala Varma stayed as a companion to young prince Avittom Thirunal. When Avittam became the ruler, the Udiyeri Nambudiris, who rose in position, entitled Kerala Varma the ‘Yuvaraja’ and instilled in him ambitions for the throne. When the Maharaja passed away, questions on the right to accession arose, and Kerala Varma claimed his right to the throne. Dramatic events followed and the then Resident2 Colonel Munroe had to intervene.

The rules of accession in Travancore do not recognize the adoption of male heirs (aanvazhi dattu). Only the son born of the Attingal Rani could ascend the throne as the legal heir. In spite of the conspirators’ effort to intimidate the yogakkars (temple authorities), they failed miserably, as the Resident was very much aware of the rules of succession. Munroe’s legitimacy and diplomacy saved Travancore when he declared Gowri Lakshmi Bayi (Swathi Tirunal’s mother) as the ruler. This period of confusion and conspiracy was an ideal opportunity for the East India Company to annex it (229-238). However, it was resolved tactfully.

Veeramma’s Satyagraha and Sati in Travancore

The Mathilakom Record sheds light on a particular instance which revealed the progressive nature of Travancore royal family in the 17th century. When sati3 was customary in India, Travancore and its visionary rulers condemned it. Queen Ayilyam Tirunal Gouri Lakshmi Bayi advocated for universal education. When vaccination was introduced, she set a model by getting herself vaccinated to clear off any apprehension regarding the vaccine among her subjects. Her sister, the Regent Queen Gouri Parvati Bayi, denied the request of Veeramma, to conduct Sati following the demise of her husband Seetharaman (a Sepoy). When permission was denied, Veeramma expressed her protest by staging a hunger strike in front of the Huzur Office in 1818—perhaps the first recorded hunger strike in the history of Travancore.

However, the government denied her permission, stating that Travancore had no custom of practicing sati, and that the State could not agree to such an unjust practice. The ruler gave instruction to the Dewan to inform the relatives of Veeramma and also spoke to them directly. They managed to change the attitude of Veeramma and sent her home issuing a grant of 500 panams for subsistence (242). That such an incident happened over two centuries ago and attracted the direct intervention of the State is fascinating in itself. It is also interesting to note that, in this case, the petitioner and the ruler were both women.

The Royal Debt

The Mathilakom Records indicate multiple instances of Maharajas pledging their ornaments for the state’s needs in times of shortage. In 1767(942 ME), Karthika Tirunal Rama Varma (Dharma Raja) pledged his ornaments to raise money for constructing Killippalam, a stone bridge across the River Killi (churuna 28/29). A few years later, in 1800, the then ruler Avittom Tirunal Rama Varma faced a huge financial crisis when the East India Company pressurized him to repay the amount paid as assistance to keep away Tipu Sultan and his army from Travancore. The amount, with accumulated compound interest, touched twenty-five lakhs. The ruler had no other way but to open the vaults. However, ‘ettarayogam’, the council of the administration, opposed the ruler’s move, since the vaults, though rich, are offerings given to the Lord Padmanabhan (Vishnu, the patron deity of Travancore), and they belonged to Him. Considering the seriousness of the situation and as a compromise, the ruler decided to pledge all the ornaments possessed by the palace in exchange of equivalent money from the vaults (78-89).

Aid to Weavers of England

It is widely known that the Travancore ruler Karthika Tirunal Balarama Varma (Dharma Raja) aided and established a village of weavers at Balaramapuram during his reign (1798-1810), the legacy of which continues till present. Interestingly, the Records show that the royal family even extended assistance to the weavers of England, who were badly affected by the loss of markets during the American Civil War. The State, through its Resident, sent an immediate massive financial aid of ₹5000 for the distressed in England (280).

Apart from details of how the rulers governed, built canals, and promoted education, science, and technology, the Records also provide fascinating insights about the sociocultural and political milieu of Travancore. Maheswari’s book has over 300 recorded events, but this constitutes hardly one per cent of the 205 original volumes. As Uma Maheswari notes, it is hard to study the still undeciphered manuscripts (in Vattezhuth, Kolezhuth, Tamil, Malayalam etc.) unless a considerable number of people are involved, and ample financial aid is made available. They not only provide us with the history and culture of the State and the Temple, but also illuminate the evolution of Malayalam language over the centuries. As such, the Records need immediate scholarly attention.

Note on the Book Author: S. Uma Maheswari, a journalist by training, has written extensively on Kerala including the region’s arts, culture and heritage for the Malayalam and English media. Her Truppadidanam, a first-person account, in Malayalam of the life and times of Sree Uthradam Tirunal Marthanda Varma, published in English as Travancore – The Footprints of Destiny, is an authentic account of Travancore, its history and culture. Her other renowned books include Sree Chithira Tirunal: Life and Times, Sree Padmanabhaswamykshetram: Charithra Rekhakaliloode (Sree Padmanabhaswami Temple: History, Culture, Tradition in English), Ormakalu 105, etc.

About the Author: Dr. Vysakh A. S. is working as Assistant Professor, Post Graduate Department of History, Sree Narayana College, Chempazhanthy, Thiruvananthapuram. His areas of specialization include medical history, social history, and archaeology. He is a research supervisor affiliated with the University of Kerala.

Very interesting to go through the contents. Uma Maheswari is known to me and she had extensively used Kerala Studies Section of KUL for her writings and I have personally helped her in accessing the documents. Mahakavi Ulloor has done lot of work on Mathilakom Records and some of them he could publish. Then also the problem of Vattaezhuthu etc was there

Whether Marthanda varma who created the centralised state of Travancore was Known as Uthradam

thirunal? I believe, he was actually ANIZHAM Tirunal.

The volume and variety of Mathilakom records from what is described above is mind boggling and wonder-some. There seems an urgent need to micro film them.If 204 transcribed volumes form only 5%Volumes of the whole,it would take at least 4000 volumes to get the whole transcribed,making it one of the largest archival collection in the world.

I plan to get it. One question. Is the language easy to understand ? Since it is history there may be archaic words that dictionaries don’t include.

Interesting and Informative article