How can we re-imagine urban planning to be non-disruptive, to promote environmental conservation and to preserve the humanity of our streets and walkways? Taking us through the undulating and thronging landscape of the city of Thiruvananthapuram, Thomas Oommen and Rajshree Rajmohan propose a solution that is both innovative and grounded in the realities of everyday life.

Thomas Oommen

Rajshree Rajmohan

Thiruvananthapuram is in the throes of a spurt of so-called ‘development’—swanky new malls, six lane highways, vehicular overpasses and ever more elaborate houses, even as its beaches disappear and its groundwater dries up. In the absence of any vision of what the city must be and what rights it should guarantee for whom, it is becoming another faceless, inhuman, ‘splintered’ Indian metropolis with unjust and preferential access to its urban commons. Here, we are talking about the denial of the right to the city—to its public space, greens, accessibility, the right to water and the right to an aesthetically rich built environment—to its most vulnerable. Can a young child and her mother amble along on our streets without being terrified of being hit by a speeding car? How do we speak of a literate, argumentative Malayali society, if it is not possible for two friends to walk abreast, lost in conversation, without the fear of falling into a drain or a pothole? In an ageing society like ours, will our countless senior citizens be able to keep their self-reliance and dignity? Will we let them cross the street for a packet of milk without the fear of being humiliated by impatient, blaring horns? Can a working-class girl feel proud as a citizen for walking to work? The answers to these questions are not heartening.

But to develop a vision of a just city, we must ask, what is Thiruvananthapuram? It is likely that for many, it is a collage of images and memories primarily of iconic urban spaces and buildings. Perhaps, the bustling Chala Market, the Napier Museum and grounds, Padmatheertham with the Gopuram in the background. For some it may be the boulevard from Kowdiar to Vellayambalam, or the winding road around the museum experienced from a red KSRTC bus. Indeed, Thiruvananthapuram is all of this and it is perhaps inevitable that the city is associated with its exceptional buildings, routes and spaces. But the city is also something far more pedestrian—to reclaim that unfortunately maligned word. What Trivandrum is hinges on something every day—our residential streets. The residential street is the urban ‘monument’ and institution to be most concerned about. Note that we are not speaking merely of roads, but streets where human beings walk, talk, meet, play and learn to be equal citizens.

Admittedly, such a thought is not fashionable today in Thiruvananthapuram’s developmental discourse. One even sees touted as solutions, modernist pipe dreams like pedestrian ‘streets in the air’ that deems to relegate the street only for automobiles.1 These schemes seem to be doomed to repeat the mistakes of 20th century urban planning which sees the city as a machine and urban problems as isolated rather than as part of a complex, emergent, interconnected system—an ecology of human and non-human agents. This does not mean we require expensive technological solutions peddled through tropes of smart cities or imported ‘world class’ experts. Rather, it is on the ground, on our residential streets and through common sense, low-tech solutions that questions of equitable mobility and accessibility, flood and drought, protection from diseases, safety from crime and accidents, will be determined. It is in the everyday spaces of our residential streets that the much hyped-about ‘Kerala Development model’ of human-centric, environmentally sensitive growth will be put to the test in a new century.

Forgotten Infrastructures

What will such a model of growth practically entail? Here, we propose a few ideas to initiate a conversation rather than outline a definitive solution. What we propose to reclaim are two infrastructures of the city that are rapidly being lost. What we would like to evoke and reinterpret is another Trivandrum—a city of streams and a city of pedestrian shortcuts. Both are separate yet intertwined stories. The latter hasn’t yet been erased from our collective memories. They still exist in the faint background of old stories from Trivandrum old-timers. Stories perhaps from an alumnus of Model School or a worker in Chala Market, one that involves walking through the city, taking mudukku vazhis2 through largely residential areas and running into an old friend (or enemy). These mudukku vazhis of Trivandrum are still in use, but they are nothing more than traffic-clogged ‘roads’ for us today. If you think about it, these mudukkus reveal something about Trivandrum: uphill from Model School junction to Thycaud, downhill from the secretariat to the general hospital, downhill from medical college and uphill to Kesavadasapuram. Uphill? Downhill? What are we talking about?

If we imagine Thiruvananthapuram bereft of human artefacts, it is nothing but a delicate ecological system of hills and the multiple streams and rivers that flows through its valleys into the sea. All else—the buildings, the roads—are merely additions. Is it surprising that we have forgotten this foundational fact of topography and ecology when we stopped valuing walking as a mode of urban mobility? Our mudukku vazhi’s of yore are often the shortest path between two points and thus often go down or uphill, they may even be along a stream in the valley, like from Pattoor to Uppidamoodu to Pazhavangadi and beyond. Notice how we have lost a sense of the ‘lay of the land’ of our city, even on our main thoroughfares. We go downhill from the secretariat, past Ayurveda College to East Fort, downhill from Palayam to Thampanoor, downhill from Thycaud to Aristo Junction. Wonder why Thampanoor floods?

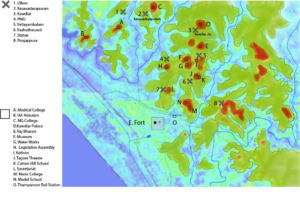

In the map below, we have deliberately erased the roads and marked only the major ‘junctions’ and buildings on a simplified topographic map of Thiruvananthapuram. The highest to the lowest in terms of height above sea level is marked from red to green to light blue to darker blue. The darker blue indicates low lying areas, places to which water will flow. Here, water table levels will be high, and ponds and water bodies form easily. Thampanoor (‘O’ in the map) is located in such a valley. Notice also the pattern of where the major institutions—royal, colonial and post-independence, of the city are located. Almost all are located on the highest points, revealing how power and the politics of urbanism and its artefacts are entangled with topography and ecology. Now, try to rethink Thiruvananthapuram, as you move through it, by going up and down its terrain. Notice how Akkulam, Ulloor, Kesavadasapuram, PMG, and Poojappura are all located on different hill systems.

Thus, the basis of this city and the key to its future—its good health—is the delicate ecological infrastructure of water and vegetation. Or as urbanists like to call it, the lines of ‘blues’ and ‘greens’. They are the lines of life, intricately entangled with the topography of Thiruvananthapuram. Unfortunately, topography is an ecological fact that continues to be forgotten in masterplans and expert discourses on ‘traffic’ and city planning. There is another dimension of urbanism and topography, one that requires a whole other conversation: how historically marginalized communities are often forced to settle in low-lying, ecologically vulnerable zones or in conventional terms areas ‘unsuitable’ for building. Thus, when the ‘blue veins’ are cut and mutilated—or worse, ignored—the ensuing flooding, drought and disease disproportionally affect marginal and poor communities. How does this entire process happen?

Deconstructing Our Streets

Mudukkus today are purely conduits for automobiles—under so much pressure for expansion that they are asphalted from boundary wall to boundary wall. Now that monsoon is here, observe how water flows in these streets. As more and more houses and boundary walls come up, the streets become the only places where surface water can flow. The surface water from most houses exit onto these streets. There is some attempt to check this with programs like mazhapolima3, but even so, in a state with the highest density of surfaced roads, our streets by themselves collect significant amounts of rainwater. With nowhere to percolate into the ground, water flows in strength downhill accumulating at some point, where, if it has access into a thodu or river, it drains. If such access has been blocked, by the absence of a culvert, by a new construction, badly engineered roads or drains, flooding results. As mentioned, this affects marginal and working class populations that are historically found in low lying areas, where such flooding can not only cause physical damage to houses, but create unsanitary conditions and contaminate drinking water supply. Even in an ideal condition, where our engineers ensure that every drop of water falling on our extensive road network flows into a drain, this water will be lost instead of percolating back into the ground and recharging our water table. Another threat is from the pollutants that water flowing through roads and storm water drains picks up and carries into our rivers and streams.

Now, how do we reclaim a delicate, respectful, everyday interface between humans and water? Between development and ecology? Big masterplans that focus on our major streams, rivers and canals in the Thiruvananthapuram metropolitan area are absolutely required, but we intend to suggest something far more local—a secondary plan and its manifestation on our residential streets and lanes that form much of our city. What follows is a modest, low-tech proposition to keep the streets that matter—our neighborhood streets—both green and walkable, and motorable at a humane speed. We start not by inventing an alien technological solution, but by tweaking existing conditions that are ‘almost all right’.

Let’s look at the growth and transformation of a typical neighborhood street. It happens in 4 stages, through 4 types of streets.

Stage 1: At some point, most residential streets were mud roads that connected together a few houses to a major thoroughfare. Stage 2: When ‘development’ occurs, most of these roads get paved with asphalt. In most cases, an earth shoulder is left on both sides. It is important to note that many of our ‘rural’ roads and ‘highways’ are like this. Stage 3: As developmental (read: traffic) pressures increase, the street gets paved with asphalt from boundary wall to boundary wall. Stage 4 involves the panchayat or public works department intervening to construct a concrete drain and a footpath as a resultant.

All of these stages or types of residential streets have significant problems. The mud road is not motorable. The Stage 2 Road has disadvantages for two wheelers, bicyclists and pedestrians because of its uneven edge. The Stage 3 Road, which is much of Trivandrum today, is extremely unsafe for the pedestrian. As can be seen from the above images, the pedestrian fights a losing battle for road space with big buses and speeding cars. With respect to Stage 4, a road with a covered drain that doubles as a footpath is a significant investment that involves many weeks of work on a road. However, there is nothing much to show for it. The slabs that double as footpath surface are unevenly and poorly cast, which result in many accidents. These footpaths are almost always cast far too high and they become extremely difficult for senior citizens and children to negotiate. But most of all, the drain gets blocked within one monsoon with garbage and soil.

Rethinking Neighborhood Streets

It is obvious that we cannot continue to follow our public works system and the misinformed rhetoric that equates well-surfaced roads with urban development. Kerala has historically made different, more grounded, locally informed choices about ‘development’. In our proposal, we take Stage 2 as a model. The advantages of the earth shoulder, even though it is ‘unplanned’, are many. It offers a space for pedestrians to be safe from larger vehicles since vehicles do not want to get off the asphalt surface. Second, it actually helps in the percolation of water that collects in these streets. The grass, plants or trees that often grow there help with this percolation, and together, it should be considered as important infrastructure. What if we dedicate a small part of our streets for a more humane city and in making sure our precious (and decreasing) rainwater is conserved?

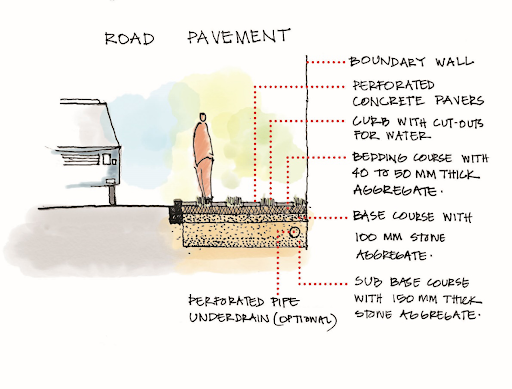

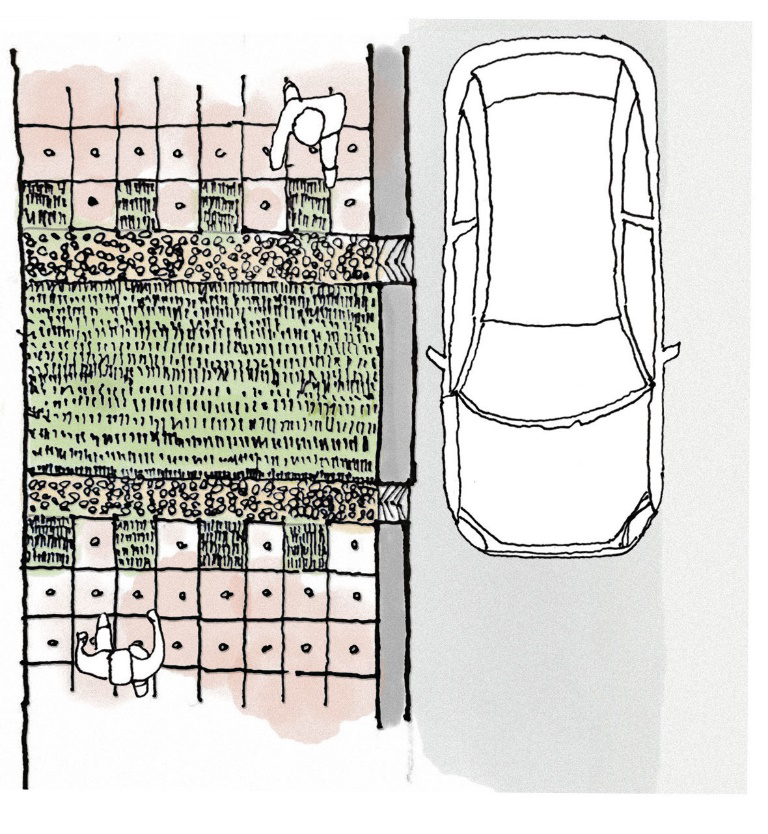

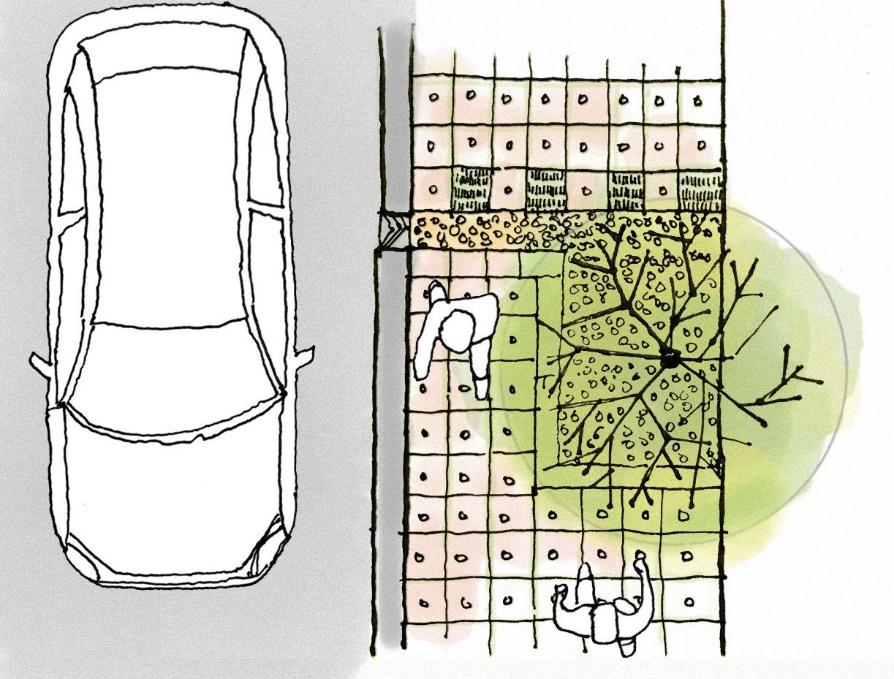

In the proposal shown (see Figure 3), 1.5 to 2 meters of space from one side of the street is taken to do precisely the above—create a safe refuge for pedestrians and allow rain water percolation. This scheme requires no concreting—a significant civil work that costs much money and time. It does require curb blocks and interlocking perforated pavers, both of which are precast and readily available. The curb block is typically a concrete precast block which can also be made with used recycled, toughened plastic waste. As can be seen in Section 1, the major work is in preparing the ground in a way that makes sure that water percolates well without uneven settlement of the interlocking, perforated pavers. Not only can this be done with simple materials (aggregate, construction debris etc.), it can be done with unskilled labor with programs like the MNREGA. However, even such elaborate ground preparation, as shown in the above section, can be restricted primarily to this ‘updated version’ of earth shoulders that we are calling ‘green zones’. These green zones which encourage more intensive percolation can intersperse the regular, more easily constructed sidewalks ( which we are recommending also be made with perforated pavers). See Figures 4 and 5 below for an illustration.

In these ‘green zones’, a curb cut directs the water flowing along the road, through a gravel channel towards a percolation zone. Zones like these can be planted with bull grass, which also offer a fairly even surface for pedestrians. In cases where there is heavy rain and there is too much water, the water flows right back out where it can be absorbed by the next ‘green zone’. There can be many variations to this basic idea, like in Plan B where the base of a tree can be used as a percolation pit.

What Thiruvananthapuram needs is a sustainable street infrastructure that combats climate change, and helps transform our residential streets into humane places fit for a just society. We need streets that breathe green and blue and are working evidence of our human and ecological values!

About the Authors

Thomas Oommen is an architect, urbanist, theorist and a resident of Thiruvananthapuram. He is currently doctoral student in architecture history, theory and society at the University of California, Berkeley. Thomas taught architecture and urban design at the School of Planning and Architecture Delhi, Sushant School of Art and Architecture, Gurgaon and R.V. College of Architecture, Bangalore before moving to Berkeley. His most recent publication is “Rethinking Indian Modernity From the Margins: Architectural Politics in Thiruvananthapuram in the 1970s” in Architectural Theory Review, Vol 22-3. He can be contacted at <thumoh@gmail.com>.

Rajshree Rajmohan is a senior architect at Chandramohan Associates and a resident of Thiruvananthapuram. Rajshree graduated from CEPT University and worked as a practicing architect and human rights activist in Gujarat before moving to Kerala, more than a decade back. She holds regular workshops at the National Institute of Design Ahmedabad and is actively involved with the academic community in Thiruvananthapuram. She can be contacted at <rajshree.ar@gmail.com>.

Illustration Credits: Thomas Oommen, Rita John

Congratulations. GREAT THOUGHTS. The city is rightly treated as an organism.