A short glimpse into the tumultuous history of Travancore’s accession to the Indian Union and the eventful end to Sir C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar’s illustrious political career.

Ullattil Manmadhan

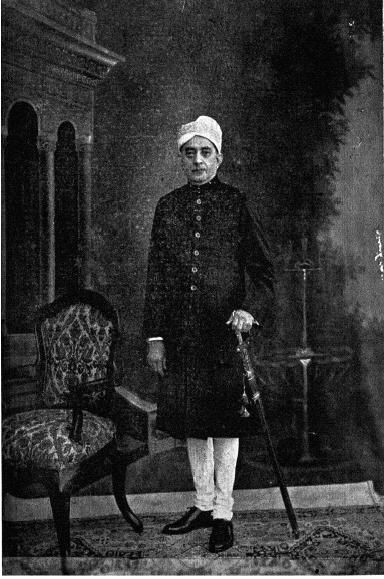

The year before Independence was a tumultuous one. While most bureaucrats in Delhi, British and Indian, were working at a feverish pitch to herald into the world scene the two separate independent countries of India and Pakistan, some others were working frantically to bring about an agreement between the princely states and the Union of India to create a single geographical Indian entity. Travancore’s efforts to remain an independent sovereign state was not only marked by the firmness of its Dewan Sir C. P. Ramaswami Aiyar, but also the stance taken by the King Chithira Tirunal Balarama Varma and Queen Mother Sethu Parvathi Bayi.

Travancore’s announcement of independence was the culmination of steps taken many years ago to resolve questions around the governance of princely states and the issue of paramountcy. What was concluded then was that the principle of paramountcy would not transfer to a future Indian government without the princely state’s agreement. Therefore, in 1946, Sir C. P. clarified his stand and asserted that Travancore would remain out of the Union of India after the lapse of paramountcy. He added that Travancore would rely upon its geographical isolation, the protection afforded by its seaboard and if necessary, try to defend itself politically and economically against any attempt at subjugation.

After the arrival of Viceroy Mountbatten, the timing for the transfer of power to India and Pakistan was decided as August 1947 and most princely states quickly acceded to the Indian Union. Sir C.P. had previously disagreed, stating in a letter to Sir Corfield, “Travancore does not wish to come into any union, which will not be a real all India union with a strong and effective central organization”1. He clarified later2 that the decision had been formalized by the Maharaja himself, adding that Travancore would have joined a united India, but now that the country was going to be divided, the princely state could not join the Constituent Assembly of a divided India. The Indian National Congress and other leaders were aghast and rose up against Sir C.P., and this was when he saw a potential ally in the Muslim League’s Muhammad Ali Jinnah, soon to be the first Governor-General of Pakistan.

Expressing his interest in cooperation with the Indian Union, Sir C.P. now decided to formulate a treaty agreement with Jinnah’s Pakistan. On June 20, 1947, Jinnah wired Sir C.P. to say that Pakistan was “ready to establish a relationship with Travancore which will be of mutual advantage”3. The Dewan, in reply, proposed that since his State was taking steps to “maintain herself as an independent entity”, a treaty be signed between the “independent Sovereign State” of Travancore and the Government of Pakistan.

Encouraged by this attitude of the Muslim League, the Dewan of Travancore announced his intention to appoint a Trade Agent in Pakistan. Dawn, then an Indian newspaper that was the Muslim League’s mouthpiece, welcomed it editorially on 23rd June 1947 under the caption “Happy Augury—it is the decision of a Hindu State to be the first to establish a friendly relationship with the Dominion of Pakistan”.4 The next step was to name a trade envoy to Pakistan, and this would be none other than Sir C.P.’s confidante and ex-inspector general of Travancore Police, Khan Bahadur Abdul Kareem Sunhrawardy. Abdul Kareem had previously served in Punjab to earn a name as a strict, honest and capable officer and was specially invited to serve the Travancore Government.

The Indian Congress reacted sharply, and Nehru exchanged furious letters with Mountbatten following which Travancore was indirectly warned that food supplies would be cut and that economic reprisals would lead to the elimination of independence in as little as three months. Sir C.P. would not be cowed—he raised the ante by negotiating for rice supplies with Pakistan’s Sindh province (as well as with Burma and Siam), offering coconuts and copra as barter. When textile mills refused to supply textiles to Travancore, he planned discussions with British and American mills. Jinnah promised Sir C.P. in return that “his Hindu Maharaja could count on food aid from Pakistan if the state decided to hold out against India”5. Sir C.P. confirms as much in his letters to Mountbatten:

I had already entered into an arrangement with Pakistan for supply as a result of threats by the Congress to cut off supplies…Mr. Jinnah was a realist and he behaved as a realist. I insisted that it was Viceroy and Mr. Gandhi who had created Pakistan and that though I had been a persistent opponent of Pakistan, at present I had no quarrel with Mr. Jinnah. I was concerned with the unity of India. It had been lost now and therefore I had come to certain arrangements with Mr. Jinnah.6

The following months were a period of turmoil in Travancore, with agitations, repressive countermeasures and many deaths. C.P. became a hated man and many a commoner wanted to see his back. Attempts at negotiation in Delhi initially saw Sir C.P. taking a combative stance, with him stating that he had more money to spend (than the Indian National Congress) to bring down the agitating masses and thwart Congress plans, even warning that he had plans to bring in Moplahs from Malabar to invade Cochin if he had to prove his point. But the Dewan eventually saw the writing on the wall, finally agreeing that accession was inevitable. He left Delhi with a draft Instrument of Accession and a personal letter to the Maharaja from Lord Mountbatten, promising to return on 27th July.

Meanwhile, matters took a menacing turn in a turbulent and mutinous Travancore when an attempt was made on Sir C.P’s life on 25th July 1947, by K.C.S. Mani, a Kerala Socialist Party (KSP) minion, when C.P. was attending the Swati Tirunal Centenary Celebrations. Sir C.P. was severely injured and had to be hospitalized. That perhaps was the last straw. He advised the Maharaja that the appropriate course of action would be to accede to the Indian Union. The Maharaja telegraphed his acceptance of the Instrument of Accession and the Standstill Agreement. An epoch had ended, and with it, the omnipresent Sir C.P. disappeared from the Travancore political scene.

Bibliography

Guha, Ramachandra. India After Gandhi: The History of the World’s Largest Democracy. New Delhi: Pan Macmillan India, 2017.

Gupta, Sisir. Kashmir: A study in India-Pakistan relations. New Delhi: Indian Council of World Affairs, 1967.

Hajari, Nisid. Midnight’s Furies: The Deadly Legacy of India’s Partition. Houghton Miflin Harcourt, 2015.

Jha, D. C. “Roots of Indo-Pakistani Discord.” The Indian Journal of Political Science 32, no. 1 (1971): 14-31.

Menon, A. Sreedhara. Triumph and Tragedy in Travancore. Thrissur: Current Books, 2001.

M. Sumathy. From Petitions to Protest—A Study of the Political Movements in Travancore 1938-1947. PhD Thesis, Calicut University, 2015.

Ouwerkerk, Louise. No elephants for the Maharaja: Social and political change in the princely state of Travancore, (1921-1947). Columbia: South Asia Books, 2009.

Pillai, Sarath. “Fragmenting the Nation: Divisible Sovereignty and Travancore’s Quest for Federal Independence.” Law and History Review 34, no. 3 (2016): 743-782.

(Ullattil Manmadhan is an electrical engineer living in Cary, North Carolina, with a deep interest in Malabar and Kerala history, penning his articles at Maddy’s Ramblings and Historic Alleys.)

Reads like a thriller! The author has gathered new facts to bring out the uncertainty of a period when Tracacore toyed with the idea of siding with Pakistan against the fledgling Indian republic!! Excellent writing.