Eliza Keyton suggests ways to improve Malayalam language education while elucidating the social landscape, student workload, teacher ability, and other factors that impact the same.

Eliza Keyton

It’s a sunny afternoon in Kochi. A family sits outside on the veranda having snacks with afternoon tea, and the parents quiz their children on what happened during school hours. They go back and forth, talking about games in gym class, a difficult math test, a friend’s new bicycle and so on. The mother goes inside to make tea while the father takes a call, and something interesting happens—the conversation, which was in Malayalam up until now, shifts to English as the children start chatting with each other.

This scene is nothing unique to many urban families of Kerala; these are signs of something a bit more insidious—Malayalee children are slowly losing their grip on Malayalam. By the time students reach high school, those enrolled in English Medium schools opt out of investing time in understanding and appreciating their mother tongue. In this situation, observers often blame parents, schools, or even the students themselves. However, multiple factors contribute towards the diminishing level of interest and support for mother tongue education. This article will briefly examine the social landscape, student workload, teacher ability, and other factors that impact how Malayalam is scaffolded and integrated into the educational environment.

The Rise of English

The role of English in facilitating mobility in an ever-globalising world cannot be overstated as it opens up opportunities for work and further studies both within and outside India. This push for English has resulted in a loss of prestige and relevance for Malayalam. From wedding invitations to government speeches, speaking in Malayalam is increasingly perceived as less prestigious. One only has to look at the fan base surrounding Malayalee politician Shashi Tharoor to see the lopsided appreciation of English. Such a preference for English, deeply entrenched in the social attitudes of Kerala, does not exist only in public space—they seep into language policies, school enrollment decisions, and funding opportunities.

The first English Medium school in Kerala was opened in 1818, with Englishmen as teachers, and paved the way for English studies for Keralites, who were motivated by the work of missionaries. English education was seen as an essential skill to obtain the chance to work in well-paid English positions. The kingdom of Travancore, under the influence of the British, established and prioritised funding for many English schools across the region, the result of this being the literacy rates that Kerala is well known for (Nair, 1976). Over time, proficiency in English has become inevitable for government work and well-paid jobs. As the idea that Malayalam medium schools are of lesser quality in comparison to English medium schools got cemented in public discourse, the enrolment rate in Malayalam medium schools came down drastically. Students, especially from affluent households are increasingly choosing English medium schools. In reality, ‘an English-medium-only education not only gives poor educational results, but it also increases social inequalities’ (Vekemans, 2018, 241). Along with creating a social imbalance through language dominance, English medium education creates a class bias. The cost of English medium education has risen over time, and this may lead to a situation where the economically backward are excluded from the benefits of mobility that English education promises.

As the perceived prestige of the Malayalam language has dropped, so has the quality of language awareness among Malayalam teachers. In 2012, a study of 800 student-teachers from thirteen Teacher Education colleges of Malappuram, Kozhikode and Wayanad Districts of Kerala found that more than 25 percent of student teachers needed to improve their competency in Malayalam (Gafoor 2013). Schools often use other subject teachers as stand-ins for Malayalam instructors, with the unfounded idea that simply having Malayalam as mother tongue enables the instructor to teach the language. This state of affairs, along with a literature-heavy curriculum with little space for analyzing text and grammar, has deteriorated the quality of Malayalam training. Students burdened with subjects like Maths, Chemistry, Physics, and other international exams avoid choosing Malayalam and opt for easier exams in Hindi or French. CBSE schools have included Malayalam in the curriculum, but a 2017 report states that these classes are not assessed, thus leaving one to question the validity and reliability of such courses (Varier 2017). In addition, Malayalam support classes do not exist for NRI (non-resident Indian) and NRK (non-resident Keralite) students who have returned to Kerala. Classes for basic Malayalam literacy are not offered to Malayalee students, and can only be found in Kerala schools with diverse linguistic populations, such as those from neighbouring Tamil Nadu and Karnataka.

Studies have shown that a solid 8-10 years of learning through a mother tongue medium followed by the gradual introduction of other subjects in a second language has much better results for the second language—in this case, English—learning (Skutnabb-Kangas 2008). For learners to fully grasp another language, they should be solid in using their home language. However, the push for the introduction of English before a child has had a chance to solidify the understanding of their mother tongue will have a detrimental effect on the acquisition of both English and Malayalam. The public preference for early introduction of English in lieu of the mother tongue, in combination with a poorly developed Malayalam curriculum, will result in students who are uncomfortable in both languages (Phillipson 2009). Students in English medium schools have reported being fined for speaking in their mother tongue, even in casual conversations with friends in school corridors. This kind of language dominance prevents the growth of the mother tongue and can make graduates feel insecure in both languages.

What is to be done?

While this imbalance of language cannot be solved quickly, it is essential to make progress towards finding a solution before the literacy gap becomes more expansive. To begin with— ensuring all school curricula have Malayalam texts, stories, and novels can make a significant impact in growing students’ minds. Pushing for teacher training and curriculum revisions in Malayalam, and upgrading the standard in which Malayalam is taught, can cause a revolution in the education system, rejuvenating passion for the subject. It will also attract talented teachers to the classroom. Students should not be forced into language use mandates, fines, and other obligatory measures. Instead, interest in one’s mother tongue must be organically stoked and cultivated, given that ‘[t]eaching everything in a foreign language is precisely what promotes rote learning without understanding and kills creativity’ (Vekemans, 2018, 240).

Despite the rise in the use of English for official matters, there are movements within Kerala insisting on the use of Malayalam in public and government spheres. A helpful example is the efforts of organisations such as the Aikya Malayala Prasthanam, pushing for government Public Service Commission (PSC) exams to be conducted in Malayalam. S. Roopima, a research scholar, performed a hunger strike for over a week in front of the Kerala PSC headquarters at Pattom with this demand (Hindu, 2019). Eventually, the exams were expanded to include a Malayalam version, and now, all Kerala State employees must be able to pass a Malayalam Proficiency exam (The Hindu, 2022). More recently, the Ministry of Education has updated coursebooks in Kerala to include a guide to reading Malayalam—a resource that had been notably absent for the last ten years in Kerala’s state schools (Manorama Online, 2022). However, these steps are only the beginning of building momentum for imparting Malayalam language skills. There must be a genuine effort to update Malayalam pedagogy and measures must be taken to fund engaging and relevant content in Malayalam courses. The English curriculum in the State must be re-evaluated and developed in a manner which complements Malayalam, not replace it.

While Malayalam is not endangered like neighbouring Konkani or the local tribal languages, it is essential for the Malayalam-speaking community to recognise trends in language policy, social attitudes, and available resources. The key to language preservation is social relevance. The activities of different social media outlets, literature movements, and grassroots organisations create opportunities to improve attitudes towards Malayalam as a language, improve the way it is taught, and improve its accessibility to locals and non-residents alike.

Bibliography:

- Gafoor, K. A. (2014). ‘Competency in Malayalam among B.Ed students of Kerala’, Endeavours in Education, 4(1), 78-86. Retrieved September 21, 2022, from https://www.academia.edu/4799453/Competency_in_Malayalam_among_B_Ed_students_of_Kerala

- ‘Hunger Stir in Front of PSC: Student Removed’. The Hindu, 4 Sept. 2019, www.thehindu.com/news/national/kerala/hunger-stir-in-front-of-psc-student-removed/article29335000.ece. Accessed 21 Sept. 2022.

- ‘Malayalam Alphabet Back in School Textbooks after a Decade’. Manorama Online, 17 Sept. 2022, www.onmanorama.com/career-and-campus/top-news/2022/09/17/malayalam-alphabet-back-school-textbooks-after-decade.amp.html. Accessed 21 Sept. 2022.

- ‘Malayalam Made Mandatory for Entry to Govt. Services’. The Hindu, 20 Aug. 2022. www.thehindu.com/news/national/kerala/malayalam-made-mandatory-for-entry-to-govt-services/article65791010.ece. Accessed 21 Sept. 2022.

- Nair, P. R. Gopinathan. (1976). ‘Education and Socio-Economic Change in Kerala, 1793-1947’, Social Scientist, 4(8), 28–43. https://doi.org/10.2307/3516378.

- Phillipson, Robert. (2009), ‘The tension between linguistic diversity and dominant English’ in Tove Skutnabb-Kangas et al. (eds.), Social justice through multilingual education. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, 85-102.

- Skutnabb-Kangas, Tove, et al. (eds.) (2009). Social Justice through Multilingual Education. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Vekemans, Tine. (2018). ‘M. Sridhar Sunita Mishra: Language Policy and Education in India: Documents, contexts and debates’. Journal of South Asian Languages and Linguistics, 5(2), 255-261.

- Varier, Megha. (May 15, 2017). ‘Compulsory Malayalam in Schools: CBSE schools in Kerala agree to obey, but there’s a twist’. The News Minute (link)

About the Author: Eliza Keyton is an education professional from the USA who has worked across several countries, specializing in English Language training, teacher development, and curriculum design. Since 2018, she has been working on engaging educational content to promote learning Malayalam. Currently residing in Vietnam, she is an Educational Consultant and is working on various text materials surrounding Malayalam literacy. You can follow her work on Instagram and Youtube.

Editor’s Note: This article is one of six articles written by participants from our 2022 Writing Workshop, and part of Ala’s fourth-anniversary specials: Issue 49 and Issue 50.

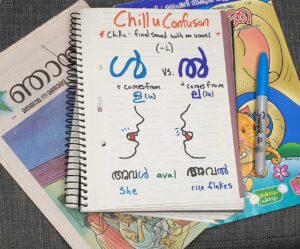

The picture shows a notebook. Are there books like this ?

Hello, This is my own notebook I’ve created as a part of the content on my page. I hope to connect with publishers soon to make printed materials of the work I’ve done over the years