Kerala’s fishing communities are besieged by long-standing social marginalisation, ongoing climate change, and the recent pandemic. The women of these communities, who are predominantly engaged in fish vending, voice the multiple challenges they face.

This article is part of Ala’s special issue on the Forecasting with Fishers project. Check out their website for more articles, interviews, and features about the project.

Johnson Jament and Caroline Osella

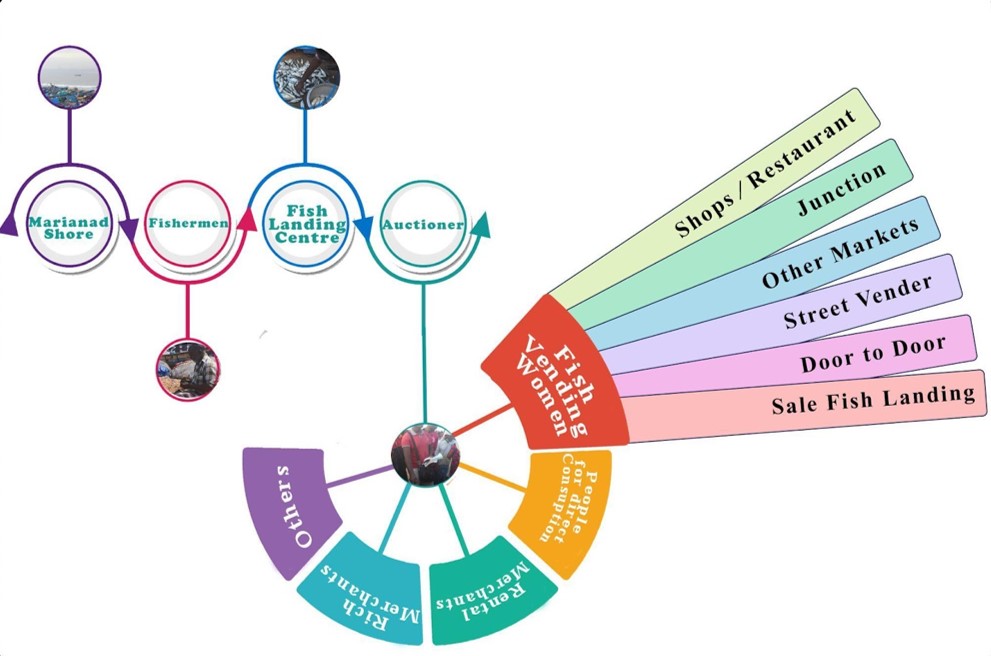

Kerala’s artisanal fishing communities continue to lead difficult lives–more than 50% of fishers’ households are deemed to be below poverty line (compared to the state average of 11%) and their economic marginality is compounded by Kerala’s caste hierarchy, which has mutated but not disappeared. Women from fisher communities are marginalized in multiple ways, carrying additional burdens from gendered norms of feminine respectability. Kerala’s fishing industry is gender-segregated: men fish, while women–35% of the fishing community workforce–take on roles including curing and processing, making and repairing nets, carrying loads, and helping menfolk. By far, women’s most significant role has been in sales. COVID-19 and successive lockdowns exacerbated this situation, restructuring the fishing industry, pushing women out of employment, and increasing economic vulnerability.

Our team at Forecasting with Fishers conducted 55 interviews with Latin Catholic Mukkuva women fish vendors from five villages across Thiruvananthapuram district of Kerala. All these villages have a concentration of active artisanal fishers and the highest number of women fish vendors in the state. During COVID-19 restrictions in the district, we collected data via telephonic interviews and WhatsApp calls, and after the restrictions were lifted, we conducted more in-depth interviews at the residences of the women. At this stage, the women felt more comfortable providing the information we sought. Our interviews made it clear that some of these women were undergoing traumatic experiences inflicted both by the public and by government officials. Field visits to fish auction locations in two villages and selected fish sales spots were very helpful to triangulate the information gathered from the interviews. We collected data from April 2020 to September 2021. These women spoke to us about their pre-COVID lives and livelihoods. They told us about the catastrophic effects the pandemic wrought upon them and their households, first by lockdowns and secondly, by the arrival of new entrants to the fish sales business. We use pseudonyms in interview excerpts below.

Before the pandemic, many fish-vending women earned enough income to support their families. While a partial withdrawal and displacement of women had already begun over recent years, our 2020 interviews with fish-vending women revealed that many families depended on women’s income for survival.

It is with my work, selling fish, that I take care of my family, my children, the debts we have, and we are surviving somehow. – Daisy

The condition of my home is such that, unless I work, my home won’t be running anymore … If I have no work, I will have to borrow from someone. – Sherly

Selling fish is not easy work, whether at the roadside for those like Jertrude,

Once I finish the chores at home…say around 8 am….We will have to buy the fish on a bid, a basket of fish will be sold to the highest bidder…we will also buy ice to keep it covered and fresh….Some of us will go to individual houses and sell the fish there. My choice is to sell fish by the roadside….There are days when I won’t be able to sell off all the fish I bought, then I will take it back home.

Or at the marketplace, for those like Daisy:

I get up early in the morning and go to the fish landing centre at around 6 am. By 10 am she has to reach the Market…and start vending…Today she reached home at around 5 pm, but most days, it would be around 7.30 and 8 pm….She was able to earn 300 INR as a profit today.

In our conversations with the women, it was clear that selling fish has always held its challenges.

I usually take fish worth 2000 to 2500 rupees for retail purposes. At times, fish can be sold for 3000-3500 rupees, but sometimes there is not much profit. Ice costs 100 rupees, and auto charge is 350 rupees. – Anna-Mary

I had to face hurdles and difficulties from men in those markets….During unloading…Union members create scenes–not allowing women to do their jobs and forcing that this unloading should be done by them at a cost of 50 rupees. – Jertrude

There was also the common concern that fish markets in non–coastal areas do not have enough toilets or water facilities.

There are issues of hygiene. – Selvi

COVID-19 brought with it new levels of precarity. Pandemic conditions impacted the whole community, but for women fish vendors, lockdowns ripped their livelihood away. First came the declaration of national curfew on 22 March 2020, followed by a nationwide complete lockdown for 67 days from 25th March-May 31st 2020. However, as expected, fish was included in the essential commodity list by both Central and state governments during this time period. Matsyafed, the government-controlled cooperative of fishers, came into the auction market to intervene in fish sales. They marked off some percentage of commission for themselves, and decided fish prices without adequate consultations with the fishers. These interventions escalated further confusion and lack of trust in government measures. There was no acknowledgement by the state of the problems with this policy – or of the government’s role in spreading confusion.

In the following months of May, June and early July, partial fishing and fish sales were allowed. However, localised outbreaks of COVID-19 in fishing villages led to fishers and women vendors being singled out and stigmatised as ‘super spreaders’, with local, parish-based total bans on fishing and fish sales for a month (22nd March to April 18th). When fishing bans were lifted, fish sales to non-coastal regions and villagers’ mobility remained restricted, allowing outsider new entrants to emerge. Kerala’s ‘triple lockdown’ strategy in coastal villages in July 2020, prohibiting all movement outside village boundaries, allowed these new sellers to establish their markets. Outsiders not under the coastal belt lockdown were able to travel into the auction market, buy fish, transport it outside the lockdown area using their own vehicles and then arrange sales directly with buyers via WhatsApp. Customers included restaurants, shops, and those who bought from the women as they went house to house. In such a scenario, fishing women’s lack of mobility and digital access left them severely disadvantaged.

New entrants into the fish market, especially youngsters with vehicles, create challenges …. These new retailers make innovations … using mobile phones, own transport systems as well as door to door marketing … Earlier, I used to sell fish worth 10,000 rupees, now I am able to do only 2,000-3,000 rupees. – Daisy

More people entered into the fish vending business. Most of them are young people … they come to the auction market with a few sacks … and take them to the markets with their vehicles.… Though these people started the fish vending job as some relief from corona-related job losses, they would like to continue this job even after corona. – Clemency

Compounding these issues, police harassment, which was always a problem, increased.

Police do not allow the vendors to sell their fish on the roadside…the CI was very hostile to the women fish vendors….They threatened the women saying that their fish and fish baskets would be destroyed…they imposed a fine of rupees 5000.… I have not paid it yet. – Mary

Police are…cruel to the fish vending women; they destroy the trade vessels and fish. – Mary-Anna

Some forms of restrictions for the fish vending women continued for months, even after COVID-19 restrictions were fully lifted for the general populace. As a result of such challenges, families that were dependent on women’s income to survive are now further enmeshed in debt and increasingly desperate.

I have been in the job for more than 25 years. Earlier, I used to earn a good amount….Nowadays, especially after corona related restrictions and entry of new retailers with much better facilities, fellow fish vending women and I had to face many challenges. – Thresia

Fish vending is the main source of income for the whole family. But after the corona pandemic, it has become very difficult for us to survive. – Jertrude

Government interventions such as centralising fish markets through ‘harbour management committees’ (where active artisanal fishers have limited representation and much less voice) have been negatively impacting fish vending women for a while now. The developmental state’s programme of urbanisation and centralisation, taking the form of initiatives such as building new ports, has also exacerbated fishers’ vulnerability and precarity. While recommendations for parallel livelihood schemes have been repeatedly discussed, there has been no action. State poverty-reduction schemes have failed to reach out to fishers.

The community is, then, caught between long-standing forms of marginalisation deeply embedded within caste society and more modern forms wrought by the state and market. Fisherwomen also suffer under the additional bane of Malayali norms of feminine respectability, which mark them as ‘not decent’ by virtue of their mobility beyond the home space and their presence in marketplace and roadside. COVID-19 has now dealt one further blow. Kerala has witnessed the positive side of structural changes in employment whereby caste-traditional specific occupations have been opened up to outsiders (such as non-Brahmins and women). However, COVID-19’s displacement of fisher community womenfolk by outsiders who have better access to digital tools and transport demonstrates the bitter side of such restructuring.

About the Authors: Johnson Jament is a Research Associate of Forecasting with Fishers Project undertaken by the School of Global Studies, University of Sussex, UK. In the previous years, he had been working with the University of Northampton for their inclusive education programmes in India. He is also a member of the coastal community in Kerala.

Caroline Osella is Research Associate at the University of Sussex, Global Studies. Caroline works as a freelance researcher/writer and has 30 years’ experience in Kerala, with a range of publications.

One comment