Urmila Unnikrishnan delves into the obscure history of the science popularisation movement in Kerala, tracing the activities of the Travancore Public Lecture Committee, which educated the common public through lectures, demonstrations, and exhibitions in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Urmila Unnikrishnan

On March 28, 1903, a lecture titled Winds was delivered at the Jubilee Town Hall in Trivandrum.1 This lecture in Malayalam, by one S. Subramony Iyer, gave a very detailed geological explanation of what wind is and the purpose of air in the atmosphere. It elaborated on the causes of uneven air heating and explained the earth’s rotation and its influence on winds. The long lecture then delved into the effects of pressure and temperature on different types of winds and discussed monsoons and other formations like cyclones. The speaker explained that a deeper analysis of everyday phenomena like wind, rain, fire or water would help to see beyond their mundanity and unravel the complex natural processes involved. Giving a scientific explanation for items, events and processes commonplace in day-to-day lives was one of the most popular tropes of popular science in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Through such explanations, interlocutors emphasised the relevance of the scientific method and rational understanding and hoped to dispel the superstitions surrounding the phenomenon in question. Similar narratives were visible in then-contemporary popular science writings also.

In Kerala, science popularisation advanced around the late- nineteenth century. By then, science had become visible in the public sphere due to the development of modern education and the popularisation of print. Local intelligentsia and the princely states were vocal about the need for scientific development and popularisation. Numerous periodicals and books published during the period underlined the need for the popularisation of modern science for the socioeconomic progress of society. Other modes like public lectures, demonstrations, museums, zoological gardens and exhibitions were also used to make science public. Although the history of Malayalam journalism and literature has highlighted popular science in print, other modes of science popularisation in the pre-KSSP era are yet to be explored. In this context, this brief note draws attention to a forgotten or lesser-known episode in the history of science popularisation in Kerala- the Travancore Public Lecture Committee.

Travancore Public Lecture Committee

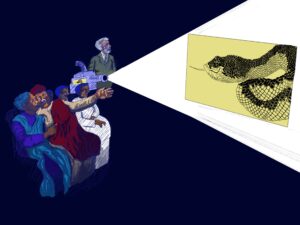

The Travancore Public Lecture Committee was set up in 1887.2 The primary purpose of the Committee was the moral and material advancement of the public through a series of lectures on topics of practical knowledge. The lectures covered various topics, including sanitation, agriculture, literature and philosophy. Partisan or political topics were not entertained. The medium of lectures was English, Malayalam, and occasionally, Tamil. Lectures were delivered in simple prose, often aided by magic lantern slides and demonstrations to make them more understandable and interesting to the public. The schedule of the lectures was prepared and published in advance in government gazettes and local newspapers.

An overview of the Committee’s report shows that fifteen to twenty lectures were delivered annually. For instance, in 1890, seventeen lectures were delivered in total- nine in English, five in Tamil and three in Malayalam. Of these, eleven were on scientific topics, and six were on literary topics. Some scientific titles in 1890 include The Coconut Palm, Electricity and The Brain. The literary titles were A Comparison of Tamil and Malayalam Language, Books and How to Read Them. While the English lectures were popular, the vernacular lectures could not attract much of an audience initially. Following this, the Committee paid more attention to vernacular lectures since they were necessary for the wider diffusion of knowledge among the general public. To increase their quality and the number of attendees, vernacular lectures were paid a higher honorarium. Magic lanterns, demonstrations and other aids were widely encouraged to attract the public. These efforts were successful, as the later reports showed an increase in the number of attendees.

Many of the lectures were delivered by the members of the Committee itself, though speakers from local intelligentsia were also invited. For instance, Harold. S. Ferguson, a noted zoologist and the Director of the Government Museum and Public Gardens at Trivandrum and a member of the lecture committee, delivered numerous lectures over the years. Some of his lectures include: How Animal Kingdom is Divided? (1889), Poisonous Snakes of Travancore (1892) and The Fertilisation of Plants (1898). Other prominent speakers include N. Kunjan Pillai (Director of Agriculture in Travancore), I. C. Chacko (The State Geologist), C. Jacob John (Assistant Sanitary Officer) and K. Parameswara Pillai (Agricultural Chemist). From an overview of the lectures delivered over the years, only one woman speaker could be identified among the list: Miss S. B. Williams. This is not surprising since the history of science suggests that lecturing on scientific topics was more or less a masculinist enterprise, at least until the mid-twentieth century.3 Miss Williams was the Principal of the H.H. Maharaja’s College and High School for Girls, where she taught English literature, history and French. Her lectures include: – Early English Life and Institutions (1896), The Beginning of the English Church (1897) and Ecclesiastical Statesmen (1898). It is also worth noting that Public Lecture Committee advertised reserved seats for ladies at their lectures. But demographics or other characteristics of the women audience are not available.

Reconstitution in 1911

Although the lectures were successful in the beginning, the initial momentum of the Committee dwindled after the 1900s, and the number of lectures decreased drastically. In 1906, the number of lectures fell to just four- three in English and one in Tamil. This state of affairs led to the reconstitution of the Committee in 1911. The reconstituted Committee adopted a more focused approach to science popularisation. Philosophical and literary themes were fewer in numbers or almost absent after the reconstitution of the Committee. Themes related to public health, scientific agriculture, industrial development and rural cooperatives dominated the lectures. This change in the focal areas of the Committee was represented in its structure as well.

Initially, the Committee consisted of faculty members from the Maharajas College, the Director of Vernacular Education, Diwan Peshkars, European missionaries and lawyers. In other words, autodidacts were major agents of science popularisation in the initial years. Later, after the restructuring in 1911, instead of including Peshkars and lawyers, the Committee was reconstituted, including the heads of various scientific departments. This change in the Committee structure shows an increasing trust in modern scientific administration. By the 1910s, the scientific administration in Travancore was institutionalised. The research and development of the socio-economic conditions of the state and its resources became more scientific and systematic. The Department of Agriculture, Geology, Sanitation Department and similar institutions were now conducting surveys, and some of these departments had even started doing well-organised public outreach programmes. Many of the officials in these departments were trained in Europe and America on government scholarships. These developments in the institutionalisation of science accompanied the changing notions of authority and expertise in science. As the history of popular science in other parts of India suggests, we see autodidacts receding into the background while scientists take the lead.4 Although the autodidact never really disappeared, they continued to be essential agents in the circulation of science through Malayalam popular print.

After the reconstitution of the Committee in 1911, more emphasis was placed on vernacular lectures. As mentioned above, the number of English lectures was high in the beginning, but most of them were delivered in Trivandrum. They catered to only a tiny group of English-educated audience based in the capital. However, with the focus on vernacular lectures after 1911, venues were spread across Travancore, covering mofussil towns. Thus for the year 1915, the Committee reported a total of twenty-five lectures. Out of the twenty-five lectures, five were in English, while twenty were in Malayalam. Eighteen of these vernacular lectures were delivered in mofussil towns attracting audiences from agricultural and industrial groups. Venues include the Agricultural and Industrial Exhibitions in Oachira and Omallore, schools and libraries. Lectures in mofussil towns were often followed by question-answer sessions to clear audiences’ doubts. The total attendance at all the lectures in 1915 was 13400. This trend continued for a few years, with the average attendance per lecture ranging between 300 to 500.

After a few years, however, lecture venues began concentrating around Trivandrum once again. To solve such issues, the Committee was again reconstituted in 1921. The new guidelines proposed an additional series of academic lectures on scientific, literary and historical themes in Trivandrum. No honorarium was offered for delivering these lectures. This may be an attempt to satiate the intellectual appetite of a more educated audience so that state resources are available for instructive lectures for the general public in the mofussil areas. Within six months of this reconstitution, the Committee was dissolved for financial reasons. Nonetheless, public lectures in Travancore continued to be conducted as part of the public engagement programmes of the Agricultural Department, the Public Health Department and the Cooperative Department.

Although the Public Lecture Committee of Travancore only has a short history of three and a half decades, its significance in the region’s social history of science and science popularisation cannot be overlooked. This event draws our attention to Travancore state’s conviction in the idea of science as a vehicle of progress and its commitment to spreading science among the public. More importantly, the Committee was one of the earliest institutions devoted to science popularisation in the region. Nonetheless, the Committee’s contributions remain obscure as popular science in Kerala is generally studied as a subset of Malayalam literature and journalism history. But clearly, the nature and the scope of the history of science popularisation in the region are much broader.

Author bio: Urmila Unnikrishnan has a PhD from the Zakir Hussain Center for Educational Studies at JNU, New Delhi. Her research interests include the history of science and popular science in India, the social history of science in colonial Kerala and the history of science education in Kerala. She can be contacted at urmila.unnikrishnan@gmail.com

Interesting. Thank you for posting. It may be added that the Trevandrum (sic) Debating Society precedes the Travancore Public Lecture Committee. I remembering reading the lecture ‘Our Industrial Status’ delivered by the First Prince of Travancore on September 26, 1874. The lecture was printed at the CMS Press, Kottayam.

— KT Rammohan