Manju Edachira writes about the re-emergence of P.K. Rosy–Kerala’s first heroine–in the modern public sphere using two theoretical interventions: “cinema within cinema”, and affective archiving.

Manju Edachira

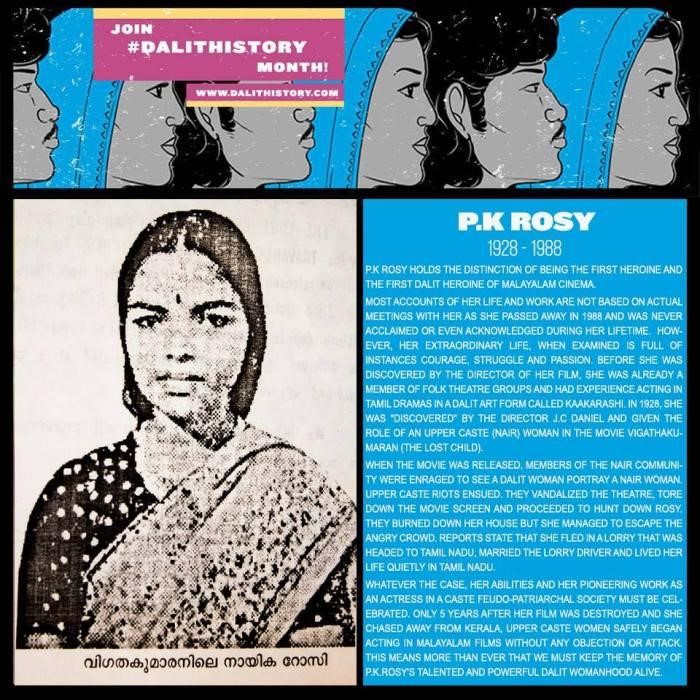

The first-ever Dalit Film Festival (DALIFF) organized in New York recently was dedicated to the memory of P. K. Rosy, arguably, the first female actor in Malayalam who was a victim of a casteist social and cinematic sphere.1 She happens to be the first heroine and the first Dalit heroine of Malayalam cinema. Rosy acted in the first silent motion picture in Malayalam, titled Vigathakumaran (The Lost Child/Boy; 1928) directed by J. C. Daniel. However, the screening of the film witnessed upper-caste unrest over Rosy (a Dalit woman) playing the role of a Nair (a non-brahmin dominant caste) woman. Furious crowds disrupted shows, and attacked Rosy and her family. This led to her exile, not only from the geographical space but also from the history of Malayalam cinema. It is significant to note that Rosy challenged conventional practices, perhaps she was a revolutionary woman of that time, who became a Kakkarishi performer (a Dalit folk theatre) and the first female actor in Malayalam. It is not surprising that her life is unarchived.

A lost figure, she was retrieved through narratives and cinema through affective archiving. This dedication, an act which recognizes her “inspiring legacy and courageous work” in the contemporary scenario, is significant in the study of affective-expressive archives and its possibilities for the oppressed communities. The term affective archive suggests the incorporation of emotions and sensibilities into the realm of historical knowledge and the effect it generates. It is at once effective and expressive, poetic and political, blurring these dichotomies. This article looks at the (re)memorialization of Rosy in the popular discourse by focusing on the film Celluloid (Dir. Kamal, 2013), which employs cinema within cinema, to narrate the history of Malayalam cinema.

Rosy’s unarchived appearance in Malayalam cinema (re)emerged recently through different modes of narrations: poetry, historical narratives, biographical fiction, and documentaries.2 For instance, Kunnukuzhi Mani’s articles on Rosy, Kuripuzha Sreekumar’s poem Nadiyude Rathri, 2003 (Actress’ Night), Vinu Abraham’s novel Nashta Nayika, 2009 (The Lost Heroine), and Kanjiramkulam Sanil’s documentary Ithu Rosiyude Katha, 2011(This is Rosy’s Story) are some of the recent notable works on Rosy apart from Celluloid.

However, one could note the difference which popular cinema, Celluloid in particular, has brought into the discourse of Rosy’s disappearance and reappearance.3 This difference is marked not only by the popularity of the form but also of the contemporary Dalit articulations on the film in the Kerala public sphere. In other words, they critically analyzed the ‘absented presence’ of Rosy in the popular cinema, and by extension, in the history of Malayalam cinema.4 Perhaps, they offer a broader critique of Malayalam cinema’s history in the present. What is more significant is the re-figuration of Rosy in contemporary discourse. This re-figuration in different locations through different means, I argue, suggests the emancipatory potential of affective archives for Dalits. P. K. Rosy memorial lectures, the proposal for cine-award in her name, the commemoration of her contributions in the Dalit history month (see image), the formation of P. K. Rosy Film Society by Women in Cinema Collective (WCC), and dedicating the Dalit film festival to the first heroine of Malayalam cinema are instances of this re-figuration which counters the lack of configuration of her presence in the industry.

These ‘external’ concerns remarkably transformed the way history is imagined and written (Nigam, 2000). Hence, Malayalam cinema’s going back to the past, especially through its own medium, can lead us to think about the complexities of present rather than the re-imagination of past. It is in this context that I found it compelling to look at the ‘aesthetics of affective archives’ from two different power locations: dominant Malayalam cinema and Dalit engagement with cinema, through form and content, aesthetics and ideology. Moreover, the subaltern history of Malayalam cinema (Rosy is a Dalit Christian woman and Daniel, a Nadar Christian) prompts one to think about oppressed communities’ engagement with cinema and modernity.

In the next two sections, I present two theoretical interventions to understand the significance of the (re)emergence of Rosy.

Cinema within Cinema in Malayalam

Malayalam cinema has witnessed a trend of cinema within cinema in the post-2000s. The film studies discourse denotes such productions as “film within film” which is considered as a self-referential or reflexive technique just like “story within story” or “play within play.” However, I prefer the phrase cinema within cinema as an encapsulating term over film within film, which is only a technical one. By cinema within cinema I refer to cinema on cinema and cinema about cinema; where the concentration is on cinema or a narrative that is explicitly conscious of the production of cinema. More precisely, cinema becomes the subject of its own (hi)story-telling (Manju, 2017). This will be crucial to understand the reflexive and the erasing nature of Malayalam cinema at once, in its self-description; where caste is the most under-examined category.

In the context where such an attempt had failed miserably in the 1980s and 1990s,5 an increased production of cinemas on cinema, and its success, especially in the post-2000s, generated certain important questions on the medium of cinema and its reception. Though there are many films in the category, I look at films which concentrated on the historical narratives and biopics of film personae. Those films used the narrative mode of cinema within a cinema to document its own history, although such movies were different in their content.

Some of the major reasons for such a trend are the “crisis” in the industry especially in the late 1990s and 2000s, the growth of soft-porn films, the emergence of new generation cinema, the increased success of Tamil and other language films in the region, the rapid growth of multiplexes, the digitalization of cinema, and the spread of satellite networks. I also look at the phenomenon of cinema within cinema in the context of post-1990s, when the consolidation of Dalit, Tribal, Bahujan and minority groups have questioned the patronizing politics of the Left, the Right and the Centrist parties (Ajith Kumar, 2013). Moreover, the period also saw the historical turn in egalitarian discourse, where the oppressed communities imagined a history for themselves (Mohan, 2010). Thus, one could note that it is at this juncture, Malayalam cinema turns towards cinema within cinema, as a mode of archiving the medium. Therefore, it is important to locate the phenomenon of cinema documenting itself within the framework of affective archiving and the manifestations of caste in cinemas of India (Manju, 2019).

Affective Archives

Recent studies on indexical documents as archives or archival practice (Amad, 2010; Baron, 2014; Russel, 2018), highlight how films generate particular conceptions of the past, rather, history itself, by invoking the term affect, both as a verb and noun. By affective archive, I suggest the presence of affect as an aspect of archive or the incorporation of feelings and sensibilities into the realm of historical knowledge (pad.ma)6 and the effect it generates (Baron, 2014). This does not suggest that the archive was devoid of affect before, but that the dominant affect was always embedded in archives though it was presented as “dispassionate” history.

Mostly, life narratives, especially autobiographies and biographies, come under the category of affective archives, as they foreground experience and feelings, rather than facts and figures of history. Bindu Menon studies the possibilities of the biopic as a form of “affective return of the past” by analyzing the discourse around Rosy (2017). She notes that “cinema and life narratives, both of which in a sense are specific kinds of exercises in memory keeping and making, offer the possibility of perpetual return, of immortality” (B. Menon, 2017:134). However, I would argue that though life narratives played a crucial role in bringing Rosy’s life history, it was the popular which facilitated the affective archiving more prominently. Especially, the archival erasure in the popular sparked discussions and debates around Celluloid and Rosy, mostly by Dalit intellectuals, which led to the recuperation of archives on Rosy. While Daniel was already recognized as the pioneer of Malayalam cinema, much before the release of Celluloid,7 this “unarchiving” (Pandey, 2014) was a watershed moment for people and Malayalam cinema to remember and be reminded of Rosy. It could be argued that though the intention of the director is to focus on the lost history of Malayalam cinema through Daniel and Chelangattu Gopalakrishnan, he inadvertently brought back the absented presence of Rosy through affective archiving.

One could argue that Dalit engagement with the hegemonic popular not only focussed on the epistemological questions on cinema and Rosy’s presence from a historical vantage point but also her experience as an artist.8 Hence, Dalit critiques, and the ensuing (re)memorialization of P. K. Rosy through different modes as instances of affective archiving, disrupts the dominant forms of archiving that constitute dominant voices as History. And most importantly, such attempts make archival gaps visible and opens up the possibilities for a historical dialogue.

Works Consulted

- Ajith Kumar, A.S. .2013. “Reclaiming the Cinematic Space: Countering the Liberal Speech on Caste.” Roundtable India, 25 February. roundtableindia.co.in/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=6270:reclaiming-the-cinematic-space-countering-the-liberal-speech-on caste&catid=119:feature&Itemid=132. Accessed on 7 June 2019.

- Amad, Paula. 2010. Counter–archive: Film, the Everyday, and Albert Kahn’s Archives De La Planète. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Baron, Jaimie. 2014. The Archive Effect: Found Footage and the Audio-Visual Experience of History. New York: Routledge.

- Manju, E. P. 2017. “Cinematic Erasures: Configuring Archives of/in Malayalam Cinema.” Caesurae: Poetics of Cultural Translation, vol. 2, no. 1, Special issue, January, pp. 29-42.

- —. 2019. Affective Archives: Caste and Contemporary Malayalam Cinema (Unpublished PhD Thesis), Centre for Comparative Literature, Hyderabad: University of Hyderabad.

- Menon, Bindu. 2017. “Affective Returns of the Past: Biopics as Life Narratives.” Biography, vol. 40, no. 1, Winter, pp. 116-139.

- Mohan, P. Sanal. 2010. “Searching for Old Histories’: Social Movements and the project of Writing History in Twentieth-Century Kerala.” History in the Vernacular, edited by Raziuddin Aquil and Partha Chatterjee. Ranikhet: Permanent Black, pp. 357-390.

- Nigam, Aditya. 2000. “Secularism, Nation and Modernity: Epistemology of the Dalit critique.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 35, no. 48, Dec., pp. 4526-4268.

- Pandey, Gyanendra. Editor. 2014. Unarchived Histories: The “mad” and the “trifling” in the colonial and the postcolonial world, New York: Routledge.

- Rowena, Jenny. 2013. “Locating P. K. Rosy: Can a Dalit Woman Play a Nair Role in Malayalam Cinema Today?” Savari, 23 Feb. https://www.dalitweb.org/?p=1641. Accessed on 13 June 2019. Russell, Catherine. 2018. Archiveology: Walter Benjamin and Archival Film Practices. Durham: Duke University Press.

About the author: Manju Edachira presently teaches at the Centre for English Language Studies, University of Hyderabad. She has recently submitted her PhD thesis on caste and contemporary Malayalam cinema titled Affective Archives at the Centre for Comparative Literature, University of Hyderabad. She works on Malayalam cinema, aesthetics, archives and caste-gender problematic. She is a former Erasmus Plus Fellow (2016) at the Film Studies Division, Freie University, Berlin. She can be contacted at manjueeswar@gmail.com

One comment