Ever since his works began to be translated into Malayalam in the mid-nineteenth century, Shakespeare’s adaptations have appeared as books, plays, comics and films in Kerala. Thea Buckley writes about the history of Kerala’s engagement with Shakespearean literature.

Thea Buckley

For how long have Shakespeare’s works been translated in Kerala? That is the question! Kerala was never fully occupied by the British, who introduced the playwright to the subcontinent. His works were added to the Indian Civil Service Examination syllabus by 1855. The region’s early assimilation of Shakespeare reflects a lasting familiar enjoyment of the author, as evident from the Malayalam translations of his works, preceding India’s Independence in 1947 and continuing till today.

The repeated reprints and high sales of Malayalam versions of Shakespeare’s works in Kerala, from the series of slim Paico Classics comics translated by R. Gopalakrishnan, to the hefty volume Shakespeare Sampoorna Kritikal [Complete Works of Shakespeare] (2000) edited by noted Malayalam playwright and translator K. Ayyappa Panicker, are indicative of a popular local reception. Panicker’s collection sold over 5,000 copies in the first three months since its publication.1 A 2012 version, Shakespeare Natakangal [Dramas of Shakespeare], comprises thirteen translations by various reputed authors like Kavalam Narayana Panicker: Romeo and Juliet, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Merchant of Venice, Julius Caesar, As You Like It, Twelfth Night, Hamlet, Othello, King L

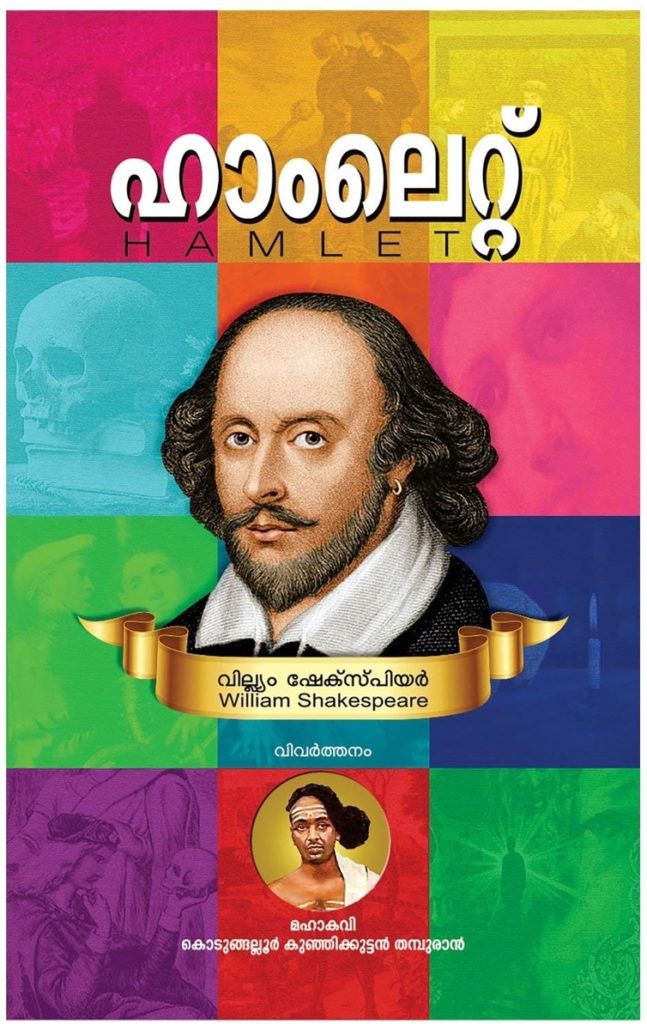

The earliest known translations of Shakespeare in Malayalam date back to the colonial era, with roughly twenty documented versions. The first of these was Almarattam [Substitution] (1866), Kalloor Oommen Philippose’s adaptation of A Comedy of Errors.2 The Merchant of Venice was translated as Porsyaa Svayamvaram [Portia’s Wedding-Choice] (1888), and Venisile Vyapari [The Merchant of Venice] (1902), and The Taming of the Shrew became Kalahinidamanakam (Kandathil Varghese Mappilai, 1893).3 In 1897, Kodungalloor Kunjikkuttan Thampuran brought out Hamlet, and A. Govinda Pillai translated, directed and acted in Brittanile Rajavu Lear [King Lear of Britain]; it was staged in Trivandrum and noted novelist and playwright C. V. Raman Pillai played Lear.4 The first Malayalam Macbeth was published anonymously in 1903 in the magazine Bhashaposhini.5 Macbeth was later translated by K. Chidambara Vadhyar in the daily Nasrani Deepika in 1929, then reprinted in 1933 as a novel, Prataparudreeyam athava Streesahasam [The Story of Prataparudram, or, the Woman’s Escapade].6 The most popular early Shakespeare translation was a musical adaptation, A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1909), which pleased the local audience tremendously.7

Malayali translators adopted individual strategies to lend more local appeal to Shakespeare’s works. Some copied Sanskrit plays, with their nandi sloka or prefatory invocation, and mix of prose and slokas.8 For Lear’s blank verse, A. Govinda Pillai used Sanskrit upajati, while K. M. Panikkar in 1959 used local keka.9 A. J. Varkki’s 1923 Hamlet retains Shakespearean names and translates the text ‘word for word’ into Malayalam prose, keeping poetry for Hamlet’s love rhyme and Ophelia’s songs.10 Varkki’s preface observes that most Malayalis know Shakespeare already through English dramas enacted by college students and through Charles and Mary Lamb’s Tales of Shakespeare.11 The Lambs’ book compiled family-friendly versions of twenty Shakespearean plays in a simple prose edition. The book was popular nationwide with students preparing for the Civil Services exam, as well as with translators.

Many colonial-era translators preferred to ‘nativise’ Shakespeare through the strategic relocation of names and places to more familiar Malayalam-language equivalents. In 1891, P. Velu, local head revenue clerk for the Nilgiris and Malabar area, used the Lambs’ version to translate Shakespeare’s Pericles into Paraklēśarājāvinṯe Katha [The Tale of King Pericles]. Velu’s translation holds themes familiar to a South Indian readership: sea voyages and fishermen; the adventures of a royal warrior in exile; a kidnapped princess; the blessing of a deity. Velu re-words the language so that Pericles’ queen Thaisa becomes ‘Dayesha’, or the ‘kind lady’; the princess Marina is ‘Samudrika’, or ‘maiden of the sea’; and the city of Tyre alters to ‘Tharapuram’, or ‘city of the stars’ (2). Thaisa’s surprise reunion with her husband, where she exclaims ‘You are, you are—O royal Pericles!’ (1.22.30) here becomes, ‘Allayo Paraklesharajave! Ningal thanneyanu—ningal thanneyanu—’ [Oh, King Pericles! You are indeed…you are indeed…] ennithrayum paranyappozhekku mohalasyappettu veenupoyi [speaking thus, she fainted dead away]’.12

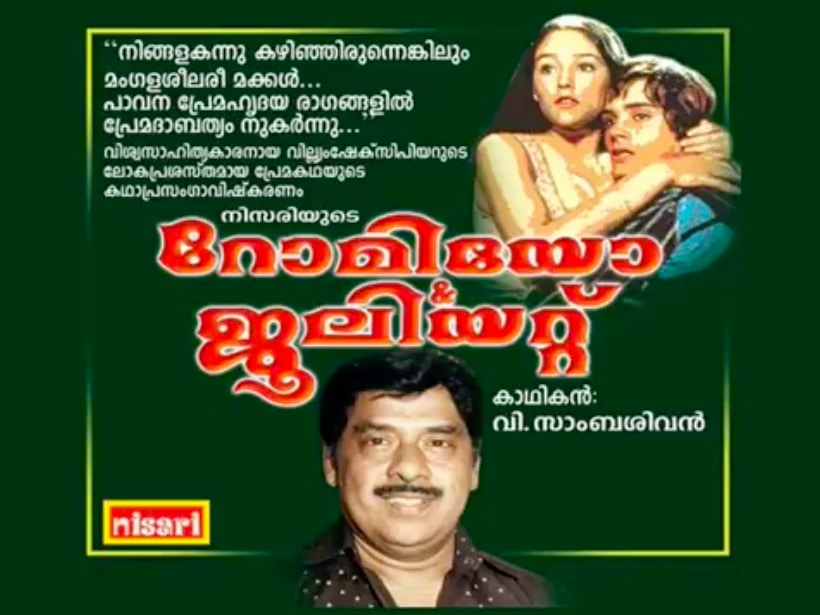

In Kerala, since Independence, translators have continued to nativise Shakespearean names and imagery with local metaphors. One such poet was V. Sambasivan, exponent of the Hindu kathaprasangam [story-declamation] art that evolved from keerthana [hymns] and harikatha [stories of Vishnu]. Sambasivan introduced world classics through kathaprasangam as part of the 1950’s Marxist Literacy Movement, presenting over decades, Malayalam ‘Shakespeare for the masses’ before thousands of people at temples, church festivals, colleges, clubs, and parties in one-hour long recital adaptations including Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet and Othello.13 He added colourful and descriptive flourishes—the Capulet and Montague families are described as ‘poisonous snakes waiting to bite each other’ while the lovers’ hearts are swathanthra, or ‘free and boundless’.14 Romeo opens Juliet’s tomb as ‘skulls and bones laugh at him’, and ‘trees shed tears of dewdrops’; the forefathers’ ‘bones and joints’ (4.3.40, 51) and ‘eyeless skulls’ (5.3.126) become the rhyming talayodukalum tudayellukalum [skull and thigh bone].15 In Sambasivan’s Othello, the Moorish hero becomes a ‘moonless night’ or ‘amavasi’ made bright with ‘the full moon’ or ‘purnima’ of his fair lady Desdemona. The prostitute Bianca is similarly embellished by being compared to the lovelorn courtesan Vasavadatta, heroine of the work by Keralan poet Kumaran Asan.16

Sambasivan also translates Shakespearean poetry faithfully into songs—in his Romeo and Juliet, the opening scene’s description of love as ‘a smoke raised with the fume of sighs…a sea nourished with loving tears…a madness’ becomes a song with lyrics including ‘neduvirrpin niraviyal …nilapukayanu premam…kannir kadalanu premam… bhrantham premam’. Similarly, the lovers’ sonnet on meeting in 1.5: ‘If I profane with my unworthiest hand / This holy shrine…’ becomes a love song, ‘Vimohaname vishudhayame vilolame karavallikalil onnu thodan oru chumbanam ekan / ninnu thudikkum adharangal tirthatakanayi thrusannidhiyil prarthippu nyan punyavati…’ [Oh beautiful, pure, soft, hands…to kiss them…as a pilgrim in the holy sanctum, with trembling lips, I pray, oh blessed lady].17Sambasivan’s translations were influential: film director Jayaraj Nair cites kathaprasangam as inspiration for his 1997 Malayalam-language film adaptation Kaliyattam [Othello], stating, ‘I encountered Othello in my childhood through this art form’.18

Today, Shakespeare remains India’s most popularly translated non-native playwright. The number of Malayalam translations of Shakespeare’s works increased sharply after the 1950s, indicating that in promoting Malayalam Shakespeares, the Keralan Communist literary drive proved even more successful than the former colonial imposition. C. C. Mehta’s Bibliography of Stageable Plays in Indian Languages (1963) contains nearly two thousand Indian-language versions of Shakespeare’s works.19 Keralites may have become acquainted with Shakespeare, on the big screen or theatre stage, at the railway bookstall or examination hall, local library or the home bookshelf. However, one thing is clear: this visitor from across the seas is here to stay, particularly when he can speak to us about shared human concerns in our own, musical tongue.

References:

- Burnett, Mark Thornton. Shakespeare and World Cinema. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- M. C., Mary Haritha. ‘Macbeth Retranslations in Malayalam: A Contextual Analysis’. Singularities: 1.2 (2014): 14-31.

- Mohanty, Sangeeta. The Indian response to Hamlet: Shakespeare’s reception in India and a study of Hamlet in Sanskrit poetics. PhD Thesis, University of Basel, 2010.

- Pillai, Kainikkara M. Kumara. ‘Shakespeare in Malayalam’. Indian Literature 7, no. 1 (1964): 73-82.

- Richmond, Farley P., Darius L. Swann, and Phillip B. Zarrilli, eds. Indian Theatre: Traditions of Performance. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. 1990.

- Shakespeare, William. Hamlet. Trans. A. J. Varkki. Kottayam: C. M. S. Press, 1923.

- Shakespeare, William. Romeo and Juliet. Trans. and perf. V. Sambasivan. Nisari, 2014. (Accessed from YouTube)

- Thomas, Sanju. ‘The Moor for the Malayali Masses: A Study of Othello in Kathaprasangam‘. Multicultural Shakespeare 13, no. 1 (2016): 105-116.

- Trivedi, Poonam. ‘Rhapsodic Shakespeare: V. Sambasivan’s Kathaprasangam / Story-Singing’. Actes des congrès de la Société française Shakespeare 33 (2015): 1-9.

- Trivedi, Poonam. Shakespeare in India: ‘King Lear’: A Multimedia CD-ROM. Poonam Trivedi, 2006.

- Trivedi, Poonam, and Dennis Bartholomeusz, eds. India’s Shakespeare: Translation, Interpretation, and Performance. Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2005.

- Valentine, Tamara M. “Nativizing Shakespeare: Shakespearean Speech and Indian Vernaculars.” The Upstart Crow 21 (2001): 117-126.

- Velu, P. Paraklēśarājāvinṯe Katha (A Malayalam Translation of ‘Pericles, Prince of Tyre’, from Lamb’s Tales From Shakespeare). Calicut: Dakshina Murthy Iyer and Sons, 1891.

About the Author: Thea Buckley is a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow, mentored by Professor Mark Thornton Burnett. Her research project, ‘South Indian Shakespeares: Reimagining Art Forms and Identities’, examines Shakespearean productions across boundaries of language, caste, media, and place in South India’s states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Telangana. Thea has previously worked for the British Library, Royal Shakespeare Company and Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, co-edited the Shakespeare Institute Review and published work in A Year of Shakespeare, Cahiers Elisabethains (2013); Multicultural Shakespeare (2014); Reviewing Shakespeare (2015); and Shakespeare and Indian Cinemas (2019). Her research is supported by The Leverhulme Trust.