What gave rise to the ‘Shakeela wave’ and the subsequent national appeal of the Malayalam soft-porn genre? Darshana Sreedhar Mini makes a case for foregrounding this ‘parallel history’ of Malayalam cinema.

Darshana Sreedhar Mini

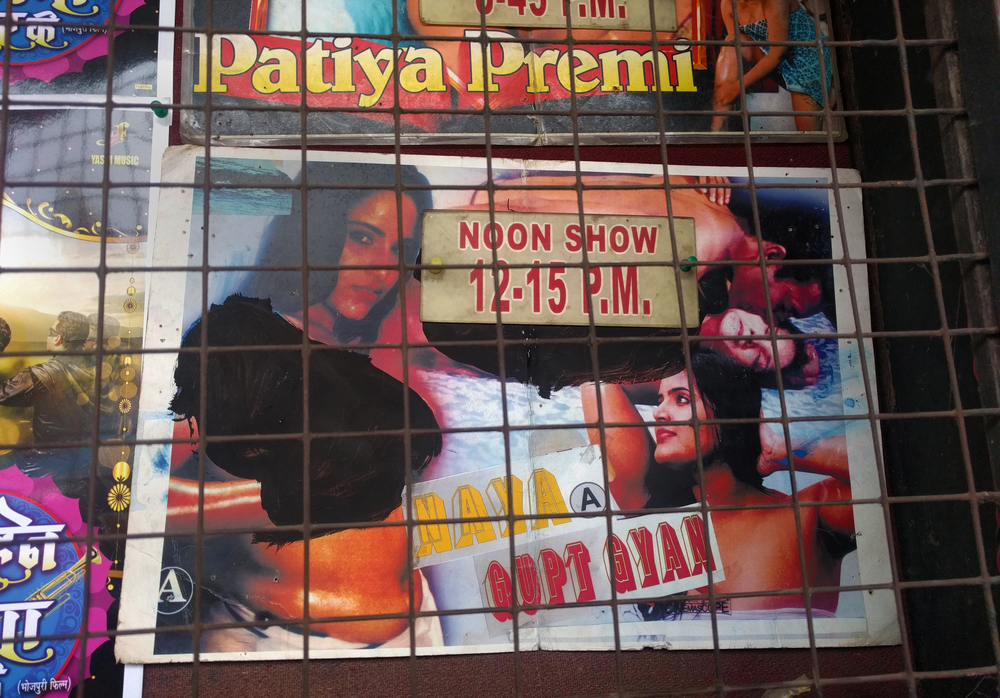

Malayalam cinema is known across the country, and perhaps the globe, for both its art cinema stalwarts such as Adoor Gopalakrishnan and John Abraham, as well as its popular male stars such as Mammootty and Mohanlal. However, there is a parallel history of Malayalam cinema that is fairly well-known, but has often been dismissed as being trivial or mere cultural trash. In the 1990s and 2000s, numerous soft-porn features began to appear in Malayalam cinema, featuring steamy sex scenes and low budgets, often at the cost of aesthetic finesse. I use the phrase ‘parallel history’ in two senses. First, in the industrial sense, whereby soft-porn had a systematic network that had unique modes and networks of production and distribution in place. Second, and more importantly, in the sense that, by focusing on female leads, soft-porn films diverged from the masculine focus of both the art cinema auteur cults, and the popular cinema action-hero fan base.

The popular memory of soft-porn in the recent past, however, has not always been sensitive to the concerns of the film personnel and actors involved. The Bollywood film The Dirty Picture (2011), publicised widely as the biopic of Silk Smitha, is a prime example of how the mainstream film industry has capitalized on the lives of starlets by projecting them as helpless victims caught in the claws of an exploitative mafia. This insensitivity is not endemic only to the film industry. In fact, when I first started discussions about my research on soft-pornography in 2011, one of the oft-repeated questions that I had to address was the relevance of working on a seemingly ‘devalued’ form. While part of this was about the cultural stigma around pornography, there was a fair amount of scepticism about the academic legitimacy of the project itself. Academic works on Malayalam soft-porn were few and far between, and by the time I had started my project, there was no more than one academic piece on it—Ratheesh Radhakrishnan’s ‘Soft-porn and Anxieties of the Family’, published in 2010.1

One vector that I locate in my larger research is to track how the figure of the madakarani (loosely translated as ‘sex-siren’)—a character-type who is sexually autonomous and confident about her desires—is inscribed and embedded in the media publics created through the production and circulation of soft-porn films. A prime example of how the film industry had utilized the potential of such a figure can be seen in the rise and fall of Malayalam soft-porn’s most iconic actress, Shakeela. In 2001, more than 70% of the total films produced in Malayalam were of the soft porn variety, and a good number of them featured Shakeela.

The soft-porn films utilized Shakeela’s ‘precarious stardom’ in two ways.2 Firstly, the mainstay of soft-porn films was the strategic positioning of the madakarani as the female lead, but also as a cultural outsider—a transient figure, both threatening, as well as a source of exoticised desire. Shakeela’s outsider status and her heavyset body type foregrounded her as the locus of Malayali society’s conflicted relationship with sex and desire while also creating a set of parallel film practices that challenged the hierarchies of the mainstream film industry. Second, and even more interesting in this regard, is the fact that, despite belonging to a regional film industry—not Bollywood—Shakeela became well-known as the face of soft-porn throughout the country. In fact, many of her films were quite popular outside of Kerala and were dubbed into Hindi as well. We can see the ripple effects of the Shakeela wave in the larger context of Indian cinema even now. A mainstream Hindi film titled Not a Porn Star, based on the life of Shakeela, is currently under production, featuring Bollywood star Richa Chadda. Also, popular erotic comics that feature married female characters as the object of sexual fantasy, such as the controversial Savita Bhabhi and Velamma, draw on the character types portrayed by Shakeela in her films.3

Shakeela, whose original name is Chand Shakeela Begum, was born in Kodambakkam to a family of Tamil-Telugu descent. In her autobiography, Atmakatha (2013), Shakeela says that her films resonated with a male audience who found expressions of their sexual desires in her body parts—a figural assemblage that also resonates with the staple sexual trope of the married ‘aunty’ figure that can be found in many a pornographic website. Popular films of the time were invested in the showcasing of heroic masculinity and silenced the agential role of women completely. Shakeela’s films, in contrast, stood out because they foregrounded her imposing figure to such an extent that the male roles in her films were functionally supplementary. In fact, most of Shakeela’s male co-stars were no more than ‘extras’, with less than exciting careers.

What is interesting to note here is that Shakeela’s status as a madakarani was partially facilitated by her own status as a cultural outsider. Malayalam cinema has, in fact, been host to a number of non-Malayali actresses who have been similarly endowed with the status of madakarani. This includes actresses such as Vijayshree who starred in films such as Panchavadi (1973) and Ponnapuramkotta (1973) in the 1970s, and most famously, Silk Smitha, who became a thriving sex-symbol in the 1980s and early 1990s. The positionality of these actresses as culturally ‘outside’ of Kerala allowed for a strange libidinal economy to emerge within cinematic representation, in which chastity was preserved for ethnically Malayali actresses whose roles were often scripted to foreground normative codes of conduct expected from the women in a patriarchal society, while in contrast, such ‘outsider’ actresses became zones of sexual access (and excess). Thus, one can see Shakeela’s emergence as a ‘porn heroine’ through an assemblage of body-parts that formed the cinematic fantasy of male filmgoers across the country, a fact echoed by Shakeela herself when she writes: ‘If I didn’t have this body, I may not have been able to make my career’.4

In that sense, Shakeela can be considered to be an extension of a cultural configuration that allowed a split between the libidinal and the cultural. But unlike earlier actresses, Shakeela was able to refashion her stardom by making her ‘otherness’ work to her advantage. Part of this strength has to do with the configuration of the soft-porn production economy itself. Whereas mainstream films were branded using the names of directors, producers, or male stars soft-porn films were mired in a kind of negotiated anonymity where the details of the crew and producer were carefully veiled using pseudonyms—often because these people were trying to juggle their soft-porn production with their careers in mainstream cinema. So, to keep their mainstream careers afloat, they often tried to hide their work in this tabooed cinematic form. It is in this context of hidden names that one has to contextualize Shakeela’s visibility and emergence. The soft-porn industry functioned using female starlets as the main attraction, and often, these starlets would appear in one or two films and then disappear, being heard of no more. Shakeela is an exception in that regard. Not only did she provide a face for these films where the production crew were often anonymous, she was also the only stable soft-porn female star—not a starlet like the others. In some ways, Shakeela is an almost impossible figure in the cultural context of Malayalam cinema, where stardom was associated solely with male actors. In fact, her impact on the industry was so strong that soft-porn films soon came to be known by the moniker ‘Shakeela films’.

It is also crucial to note that the emergence of the genre of soft-porn in Malayalam cinema was itself a product of a film-industry crisis in the 1990s, when a number of films began to fail at the box-office. Soft-porn thus became a sort of a parallel ‘savior’ industry that provided a means of livelihood to many filmmakers and technicians that began to work in soft-porn films simply for survival. In that sense, these ‘Shakeela films’ became crucial to this wider economy of survival, with Shakeela’s presence ensuring revenue and thus, survival for these personnel. Shakeela’s emblematic presence at a time of economic crisis destabilized Kerala’s hero-centric mainstream industry for a time, leading to what was popularly called Shakeela tharangam, the ‘wave of Shakeela’.

About the Author: Darshana Sreedhar Mini is a PhD Candidate at the Cinema and Media Studies Division, University of Southern California. Her dissertation explores precarious media formations such as low-budget films produced in the south Indian state of Kerala, mapping their transnational journeys. Her work is supported by the Social Science Research Council and American Institute of Indian Studies. Her research interests include feminist media, gender studies, South Asian studies, and media ethnography. She has published in Feminist Media Histories, Bioscope: South Asian Screen Studies, South Asian Popular Culture, Journal for Ritual Studies, and International Journal for Digital Television.