Shafeeq writes about the need to re-imagine migration through the everyday stories of those who travel, and away from the tired stories of economic and social mobility

Mohamed Shafeeq Karinkurayil

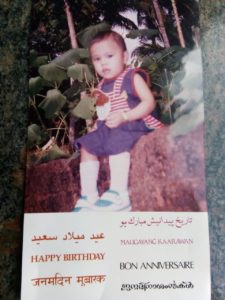

In the twelfth year of his life as a migrant, Kareem (name changed) sent his daughter, who was turning two then, a postcard from the Gulf. The year was 1994. Kareem worked as an office boy in an educational institution in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). He would go to his family in Kerala once for three months every two years. The postcard he sent prominently displays a picture of his daughter sitting by the wall of their house in Kerala. Vegetation juts into the foreground from the behind the wall. In the deep background, coconut trees stand tall. This photograph was sent to him by his wife who had never left Kerala, through another migrant labourer. The photograph covers almost two-thirds of the postcard. The bottom portion of the postcard features seven languages. Kareem’s family would have found Malayalam, Arabic, and English familiar to read, with their level of comfort with each of these languages varying greatly. Malayalam was the mother tongue, Arabic reading compulsory for liturgical purposes, and English readable to some extent. They all wished the equivalent of what in English is “happy birthday”.

In this article, I take this postcard as a context; a letter that is also an act of mimicry where the signifier exceeds the message. A playing around; a display aimed not at any individual in particular, but to the very world which gives individuals their meaning and purpose. A letter of intent addressed to the symbolic structure of our lives. After all, what are all these foreign tongues doing on that postcard? What do they intend to convey? To borrow Benjamin’s words, what foreignness flashes through in a postcard that should have been an act of intimacy, a paternal nod of care and remembrance? The postcard, as was/is the practice, did not come by post. Instead, it was enveloped, along with letters to the family, and sent through another migrant labourer, a relative or a friend who was visiting home. These were letters meant to be read in private, and letters meant to be read in family gatherings. Letters which would make clear its addressee in the opening paragraph, after invoking God’s name, and immediately after naming the love—priyam, sneham. Letters which had generic beginnings, dictated by convention, words that carry the imprint of its use that anywhere else would feel out of place. And there, enveloped by the worn out and the familiar, a postcard flashes the foreign; an uncanny postcard which carries the image of its addressee, a child of two for whom every alphabet is foreign.

It is precisely this cut of foreignness in the migrant experience that I want to engage with. Academics, as we know, is often an exercise in hindsight. It is more of an occupational hazard. However, the academic imagination can perhaps entertain and experiment other possibilities? Perhaps though the narration happens at the end, the order of narration can begin at the beginning?

What does it mean, in the context of migration, to begin at the beginning? If one is to look at how Gulf migration in Kerala is studied, one sees majorly the economics and the social aspects scrutinized from the vantage point of some quarter of a century (and more) of Gulf migration behind us. The migrant fits into a story that is familiar, that is charted even before he set out his journey. This story has winners and losers, upheavals and happy endings. The grids of this story are already in place—remittance, GDP, caste, community, gender. In this story, the migrant never leaves home. He is here, available as a familiar blip, or even as a family member. Perhaps this is why Goat Days shook our imagination.1 For the first time we were made to see what migration means, that migration is in fact disappearance, getting lost in a landscape, bound by an unknown tongue, caught up in an unfamiliar job, stung by hardship, companioned by tutelage and solidarity. The novel reminds us (or it ought to) that even though not every migrant is lost in a sea of sand with only goats for company, every migrant makes this journey through unformed signifiers and sounds that do not mean anything but play in the background of his sleep with their curious twists, suspenseful pauses, unforeseen elongations, startling comebacks and happy conjoinings.

That this shaking up from a story of familiar nostalgia when it happened, had to happen in fiction, is just another reminder of how migration has been for academics an object of study shorn of its fundamental experience—that of being caught up in the foreign and the unknown. When a pair of legs fit into a pair of trousers for the first time because the familiar wrap-around lungi is not a choice; when a body proceeds to act on his bosses’ order even though much of what the boss said was unintelligible; when frozen khubz is the breakfast one has if at all one has breakfast – when the experience is put to comparison with what was back at home, the researcher inevitably is entangled in the narrative of nostalgia. But the very strangeness of these experiences in themselves—of cloth sticking behind one’s thighs and knees, of the immense risk and decision-making involved even in carrying out what is objectively “doing one’s duty”, the feeling of cold food in mouth—is perhaps worth considering, if only to recover a different story of a people. A study which has sought to reconstruct some of these experiences has recently come out. M.H. Ilias has documented the experiences of many of the early migrants to the Gulf. These are migrants who had left for the Gulf in the 1950s and the ‘60s when the Gulf as we know it now didn’t exist. In his work, we see a recollection of the strange encounters, of kind locals, helpful policemen, etc.2 An entire generation, however, is still waiting to be heard.

It is well-known that the Gulf migrants played a crucial role in democratizing various technologies in our countryside—the tape recorder, camera, etc. However, the story often takes the tone of a given. One forgets at least two different episodes that should have been part of this story—one, the sheer sense of discovery of the initial days in handling any of these technological devices, and two, the fact that the songs to be played and the photographs to be taken came after the technology itself. This is indeed the foreignness of migration; that a body exists—the purpose of which is a radical possibility. One makes the detour through Rafi and Kishore Kumar, singing half-known, half-intelligible lyrics before one arrives—indeed, one composes—the familiar tunes, which then are already in a shadow of the foreign. One imputes to one’s skill the art of reproducing images from billboards and magazines, with pictures from a world which is yet to be known, into one’s own device.

Before the migrant fit into our tired stories of economic and social mobility, he was mobile, encountering the infinite other with whom he could have come to terms with only through immense curiosity, patience, dread, kindness and generosity, and above all, with a commitment to being open to the possibility of the everyday. This story of migration demands an academic practice.

About the Author: Dr Mohamed Shafeeq Karinkurayil is a Post Doctoral Fellow at Manipal Centre for Humanities, a unit of Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE). He received his PhD in Cultural Studies from the English and Foreign Languages University (EFLU), Hyderabad. His current research is on cultures of migration. The author is indebted to the conversations with Ms Archana Ravindra, MA student at MCH, in the overall conception of this paper. He can be contacted at shafeeq.vly@gmail.com

Beautiful piece – thanks for putting the phenomenology of migration and the embodied experiences of individuals to the forefront. We need this. I’ve re-posted with enormous pleasure. (https://blogs.soas.ac.uk/osella-realm/en/2019/04/30/putting-travel-back-at-the-heart-of-migration-stories/)

Lovely, too, that it came out same week as this one got a write-up – https://blogs.soas.ac.uk/osella-realm/en/2019/04/28/instagram-chronicle-of-gulf-migration-and-memories/

Thank you for your kind words. It means a lot!! Also, very excited to know about the REALM project.