How accessible is Kerala’s much-lauded public education system? Sreejith reviews O.P Raveendran’s new book that explores this question by studying the aided schools in Kerala.

Sreejith Murali

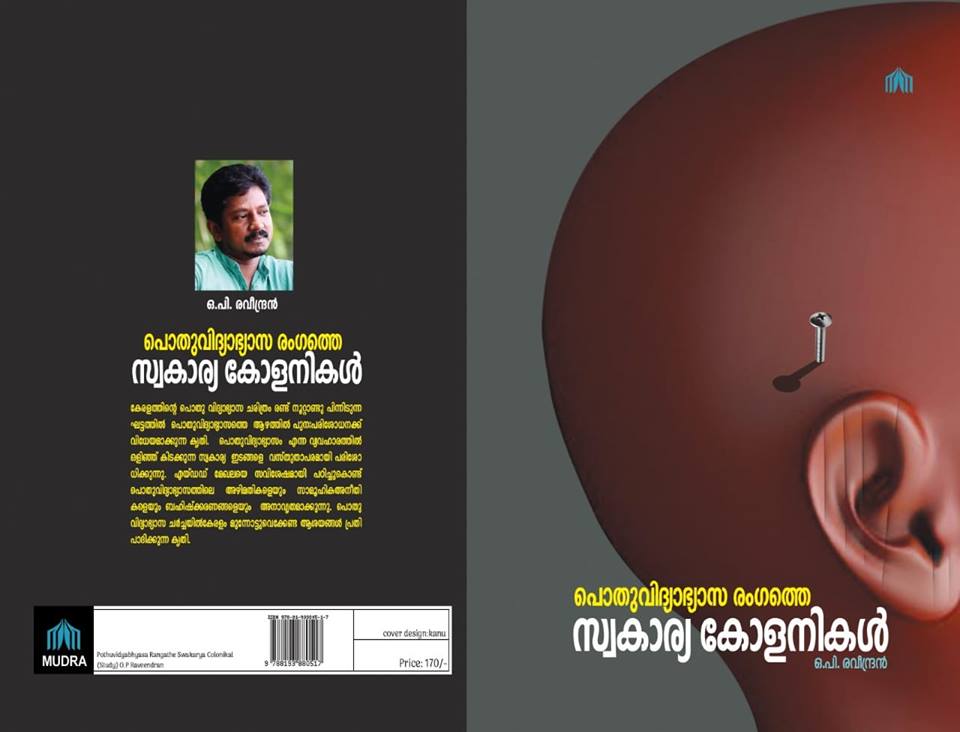

O.P. Raveendran, പൊതുവിദ്യഭ്യാസരംഗത്തെ സ്വകാര്യ കോളനികൾ [Pothuvidyabhyasa Rangathe Swakarya Colonykkal]. Kozhikode: Mudra Books, 2019. 152 pages. Rs. 170.

Education in India is often discussed through the binary of public and private within dominant scholarship, with an assumption that public institutions have more democratic access. It is within this context that contemporary efforts to ‘save public education’ are articulated. While it is of critical importance from the perspectives of equity, constitutional rights and social justice to provide for high-quality public education, scholars have to interrogate whether these institutions are inherently equitable just because they are state-funded. Raveendran’s book tries to answer this question of what parameters can make public educational institutions truly equitable. It probes whether the system of public education in Kerala has upheld principles of social justice. The author, O.P. Raveendran, has been associated with various social movements concerning Dalits, Adivasis and other marginalised communities and has earlier edited a book with writings of Rohith Vemula translated into Malayalam. How ‘public’ are these institutions? Have they implemented equal opportunities and equal justice for all communities? Is Kerala’s famed public education system a model to follow? These are the critical questions that Raveendran’s present book engaged with (pp 11-12). This book will also find its place among the growing literature that questions the uncritical appreciation of the Kerala Developmental Model.

The social pattern of staff recruitment in publicly funded privately owned (government aided) educational institutes–both schools as well as higher education—is analysed in the book, along with social and legal struggles in the history of reservation in the state of Kerala. Through detailed historical and contemporary analysis of the statistics, case histories and social struggles, the author concludes that Dalit and Adivasi communities in Kerala have not been equally represented in these institutes even though they depend heavily on the state budget, thereby violating the principles of social justice enshrined in the constitution.

The book’s name takes from how the history of public education in Kerala is tied to the history of how the dominant communities in Kerala—Nairs, Christian, Ezhava and Muslims, used aided educational institutions to create “private colonies” for their own respective communities. The book has shown that despite being established, maintained and developed by the state budgetary allocation, the aided sector in education in Kerala has not been truly “public” in nature. When attempts were made by the state legislature to make laws for reservation for Dalit and Adivasi communities, the dominant communities resisted through agitations, legal cases and political pressure to deny other communities equal representation. The extensively researched chapters provide a history of public education and aided institutions in the state, quantitative data on a large number of such privately owned government-funded institutes that get a significant portion of the state’s budget, and the low representation of Dalit and Adivasi faculty in these institutes. The book also lays bare the empty anti-reservation stance of the savarna communities who in fact ‘reserve’ seats even up to 80-90 % in aided institutions run by them, an example cited is the Nair Service Society (NSS) run institutions.

The book focuses on two interrelated themes. Firstly, it discusses how few dominant communities in Kerala who took to establishing private schools and colleges maintained hegemony in recruiting staff from their own communities while thwarting legislative and legal attempts of recruiting staff from Dalit and Adivasi communities. Parallel to this theme, the historical and contemporary struggles of Dalit and Adivasi communities to ensure constitutional representation in these public-funded institutes are discussed. There is less than one per cent representation of Dalit and Adivasi communities in teaching and non-teaching staff in aided institutions (p. 30), thus building a case for state-mandated reservation policies to be followed in these institutions. In this context, legal remedies were sought by Dalit and Adivasi activists to ensure reservation in the aided sector but were resisted yet again by powerful caste organisations. The author rightfully argues by analysing the history of reservation in Kerala that most communities, especially the savarna communities like Nairs, who oppose current reservation policies, have been beneficiaries of the policy at some point in time. The case in point being the Malayalee Memorial submitted by majorly prominent Nairs in Travancore decrying the dominance of Tamil Brahmins in administration and wanting a reservation for native elites. The book ends with bringing the focus back to the social inequalities within the aided sector in Kerala. The author reiterates that the aided educational sector in Kerala which forms a significant portion of all government staff receiving salaries ‘reserves by design’ its staff strength for their own communal interest. Particular focus is laid on how different community-based organisations like the various Christian churches, the NSS, Sri Narayana Trust (S.N.) and prominent and rich Nair households started private schools which received grants from the state. Among all the educational institutions that are funded by the state government, schools and colleges, 61.11 per cent of total educational institutions are aided, and colleges account for 79.36 per cent of this (p. 28). 66.59 per cent of school and college teachers getting salaries from the government are in the aided sector (p. 29). Detailed statistical information in tabular format is used by the author to show that the aided institutions are held primarily by four social groups in the state and have less than one per cent representation of Dalit and Adivasi communities in their teaching and non-teaching staff. The book also has an extensive list of appendices with relevant documents and case judgements.

This work does not stop with a scholarly analysis of the history of aided educational institutions and the question of social justice; for the activist in the author, it is an urgent appeal for rectifying centuries of injustice borne by Dalit and Adivasi communities within the education sector. As the author eloquently argues, the struggle against these ‘private colonies’ within public education is exemplified by the most recent legal battle to ensure social justice. A case was filed by Dalit and Adivasi government service personnel, students and activists arguing for reservation of staff in aided educational institutions. Legal battles followed for long five years ending in a ruling to reserve positions in teaching and non-teaching posts for SC and ST communities. The NSS and the S.N. Trust appealed against this ruling, culminating in a Division Bench ruling in 2017 which, through the stroke of a pen, denied the possibility of ensuring social justice and a loss of some 10,000 jobs in state government for these underrepresented communities (p. 55). The author comments that it is a terrible irony that the ‘uneconomical schools’ with low enrollment—a majority of which are aided–have significantly large Dalit, Adivasi and backward communities while the teachers in these schools belong to dominant communities. The book ends with the question of whether the Kerala government and public sphere will show the strength to ensure equality in the “private spaces” that aided educational institutions have become and convert them into public space that goes beyond caste and religion (p. 103). This book is an important read for educational activists, academicians and the general public who are interested in the matter of education and the state’s role to provide constitutional rights.

Sreejith is a PhD student of Sociology at Department of Humanities and Social Science, Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay with a research interest in the history of education in Malabar looking at caste domination, state-society interaction and educational policy. He is a student of Ambedkarite philosophy of social justice and strives to work from Ambedkarite ideology in education. He can be contacted at sreejithmanu@gmail.com

Excellent review Sreejith. Most pertinent points have been well highlighted with lot of brevity.

Sreejith what is the share of the aided sector in public education? Do they have more schools than fully government schools? What percentage of Kerala’s school kids go to aided schools? In terms of resources/funds, ie tax payer funds, what percentage of government funding goes to aided schools, and what percentage does government schools get? Do you have a break-up in numbers across the state? Thankyou for the review. It’s good. Ravi’s book needs more visibility and follow-up research and writing on this issue.