Billboards advertising luxury condominiums in Kochi, with their roof-top infinity pools, waterfront balconies, French windows, and Italian marble floors, are difficult to miss for any passing by the city. Reflecting on the rise of these new living spaces, Siddharth looks at what it tells us about Kerala’s changing urban space and social life, and its ties to the state’s altering migration patterns.

Siddharth Menon

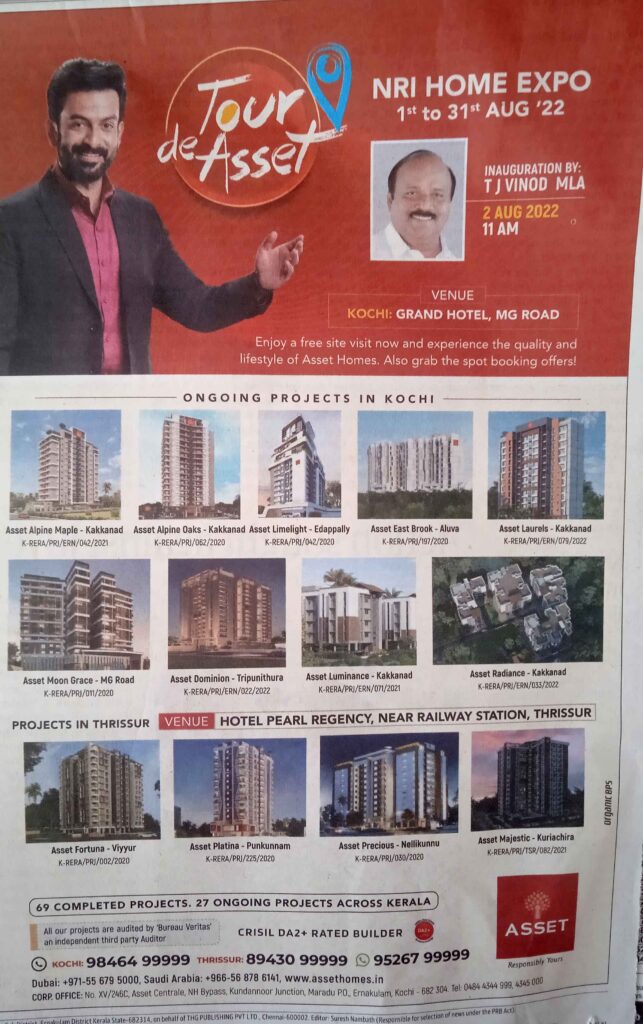

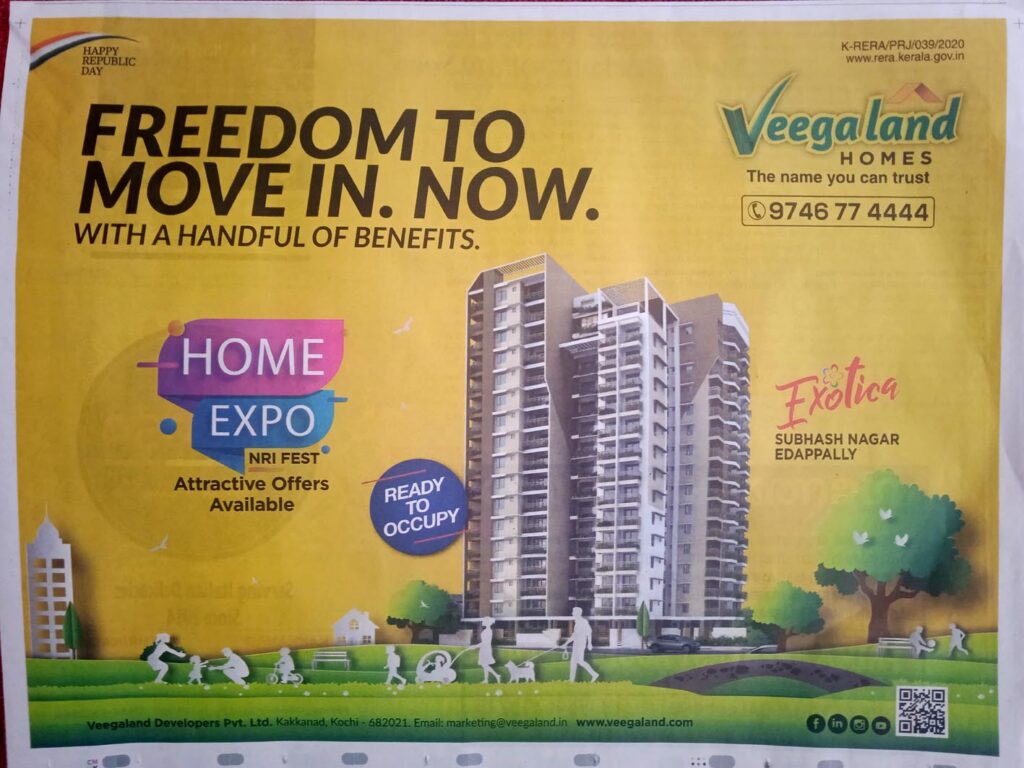

As you exit the ‘world’s first green airport’ in Nedumbassery on the outskirts of Kochi, your eyes are drawn to a series of multi-colored billboards along the major highway. Many of these larger-than-life neon-lit hoardings advertise luxury condominiums, exclusive gated communities, and spacious ‘flats’ in the city. Extravagant phrases, like ‘premium’, ‘new luxury’, ‘spectacular’, ‘next-level’, and ‘world-class’ immediately catch one’s attention. These phrases are accompanied by glitzy images of roof-top infinity pools, waterfront balconies, fitness clubs, mini-theaters, French windows, Italian marble floors, and US-style bathroom fittings. Similar scenes can be witnessed in other rapidly developing cities of Kerala, like Thiruvananthapuram, Kozhikode, Kannur, and Thrissur,1 as well as those in other parts of India. But what do these billboards tell us specifically about the state’s changing built environment, political economy, and urban social life?

Since the liberalisation of India’s economy in 1991, and the subsequent entry of foreign direct investments (FDI) into Indian real estate in 2005,2 the production of urban space in India has been increasingly dominated by the interests of global investors and local real-estate developers (Searle 2016). During this time, large metropolitan megacities like New Delhi, Mumbai, and Bengaluru have witnessed the widespread construction of elite infrastructures, including airports, metro-rails, IT parks, shopping malls, hotels, and luxury condominiums. These infrastructures cater to the globalising tastes and consumption practices of India’s affluent upper-middle classes, who constitute less than ten percent of its population. Entrepreneurial state and municipal governments have also actively tried to attract foreign investments to facilitate this infrastructure boom (Gidwani et al. 2024). Indeed, developing cities across the world are competing with one another to attract foreign funding for such ‘world-class’ projects, a process researchers have called ‘worlding’ (Roy and Ong 2011). Such projects increasingly depend on global financial instruments, such as private equity, real estate bonds, and infrastructure investment funds, rather than public-sector funding.

We see similar urban transformations occurring in smaller tier-II and tier-III Indian cities, like Kochi, that are often overlooked within mainstream discourses about globalisation and urban development. Over the last two decades, Kochi has witnessed the construction of its own ‘world-class’ infrastructures, including the world’s first fully solar-powered international airport, India’s largest shopping mall, India’s largest convention center, south India’s largest football stadium, a 45-km elevated metro rail corridor, 5-star hotels, IT parks, and luxury condominiums. But unlike major metropolitan cities that are being shaped by global financial instruments,3 Kochi’s urban transformation is being facilitated by a more familiar infrastructure of finance: Gulf remittances, or the funds sent back by Gulf-based non-resident Indians (NRIs).

Kochi’s and Kerala’s tryst with remittances is not new. Since the 1960-70s oil boom in the Arabian/Persian Gulf States, Kerala has witnessed a mass migration of working-class people to the oil-rich region to work in primary, secondary, and lower-level tertiary sector industries, like oil and gas production, construction, transportation, repair, maintenance, and housekeeping. The flow of remittances from these workers saw the emergence of the State’s first ‘Gulf houses’— palatial bungalows that concretised the dreams, aspirations, and social status of Gulf migrants (Wright 2021). But things have changed in recent decades. Not only has the quantity of blue-collar Gulf migrants decreased due to economic headwinds in the region post the 2008 financial crisis,4 but so has the demographics of Gulf migrants, which now include more women, younger professionals with higher-ed degrees, and other white-collar workers employed in higher-level tertiary and quaternary sectors, like media, medicine, engineering, architecture, real estate, finance, and IT. This demographic shift has also triggered a shift in Kerala’s built environment. Instead of constructing independent Gulf houses in their rural hometowns, newer Gulf migrants prefer investing in urban ‘flats’, i.e., luxury apartment units in multi-storey condominiums that offer ‘world-class’ amenities and are easier to finance, manage, and maintain from afar (Varrel 2020). This moneyed demographic acts as the primary consumer base for Kerala’s real-estate industry, causing it to grow rapidly.

Over the last two decades, Kerala-based developers have actively courted the Gulf NRI market. Most developers host lavish NRI home ‘expos’ and ‘fests’ in Kerala, placed strategically at star hotels, malls, and restaurants frequented by wealthy NRIs, attempting to sell luxury flats. Many developers have satellite offices in Gulf countries, like UAE and Saudi Arabia, that are staffed by sales and marketing staff. Smaller developers may not have a dedicated office space but will retain one or two employees working out of a co-working space. Some may not even have a permanent physical presence in the Gulf but will still display UAE-registered phone numbers on their websites which will be managed by sales personnel based in Kerala.

Furthermore, new real estate projects in Kerala are almost always launched first in the Gulf to collect advance bookings and kickstart construction financing. A team of senior sales/marketing executives from Kerala will travel to the region where they will host multiple ‘roadshows’. These events will usually be conducted at prominent convention halls and will be accompanied by Malayali cultural performances. Some even fly in Malayalam film stars as brand ambassadors to help attract eyeballs and generate sales. Others advertise these events on Gulf-based Malayalam radio shows and local newspapers. Typically, the sales team will travel from one Gulf country to another to conduct a series of events before returning to India. Apart from organising individual events, developers also collectively participate in annual third-party property shows in the Gulf often organised by major Malayalam newspapers, like Mathrubhumi and Malayala Manorama, that receive significant ad revenue from real estate developers. In effect, the Gulf NRI market is the primary market for Kerala’s real estate developers. This was reinforced by a prominent Kochi-based real estate developer, who said, ‘There are not enough local buyers for luxury flats in Kerala. We rely mainly on sales to Gulf NRIs, who constitute more than 70% of our customer base. In fact, Kerala’s real estate developers were pioneers in selling real estate to NRIs. In the early 2000s, north Indian developers would fly down to Kochi to take lessons from us on how to market their projects in the Gulf. While the rest of India was just entering the NRI market, Kerala’s developers had been already doing it for a decade.’5

To circle back to my opening question, the innumerable real-estate billboards scattered across Kochi’s and Kerala’s landscape signal a modal shift in its urbanism: from Gulf houses to NRI flats. While both urban forms are tied to remittances, there are significant differences. The former cemented the aspirations of first-generation Gulf migrants who used their remittances to construct stable houses and climb the socioeconomic ladder out of poverty. The latter however, give shape to the ‘world-class’ ambitions of recent migrants who invest their remittances in flats as asset classes and luxury holiday homes. This shift dovetails with the larger trend towards the premiumisation of the Indian economy which has seen a significant rise in the consumption of luxury goods over the last few years. But this premiumisation has also furthered economic inequalities as witnessed in Kochi. While it undergoes a ‘world-class’ urban transformation catering to the needs of its diasporic elites, it simultaneously makes parts of the city inaccessible to its marginalised lower classes, many of whom also belong to historically oppressed lower-caste communities. For these reasons, the everyday practices of transnational urban actors, like real estate developers and elite NRIs, need to be taken seriously when imagining the future of cities in Kerala and other parts of India.

References

- Department of Industrial Policy & Promotion. (2005). Press Note 2. Government of India,

- Ministry of Commerce and Industry.

- Gidwani, V., Goldman, M. & Upadhya, C. (Eds.). (2024). Chronicles of a Global City:

- Speculative Lives and Unsettled Futures in Bengaluru. University Of Minnesota Press.

- Harvey, D. (2009[1973]). Social Justice and the City. University of Georgia Press.

- Rajan, S. I. and Zachariah, K.C. (2019). Emigration and Remittances: New Evidences from the

- Kerala Migration Survey, 2018. Center for Development Studies, Working Paper 483.

- Roy, A., & Ong, A. (Eds.). (2011). Worlding Cities: Asian Experiments and the Art of Being Global. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Searle, L. G. (2016). Landscapes of Accumulation: Real Estate and the Neoliberal Imagination in Contemporary India. University of Chicago Press.

- Varrel, A. (2020). A job in Dubai and an apartment in Bangalore. City, 24(5–6), 818–829.

- Wright, A. (2021). Between Dreams and Ghosts: Indian Migration and Middle Eastern Oil. Stanford University Press.

About the Author: Siddharth Menon is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Geography at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA. He is thankful to the Ala editorial team for their insightful feedback which has significantly improved this essay.