How is the Mappila ‘qualified’ in Malayalam Cinema? Ahnas Muhammed dives deep into the popular cinematic representations of the Malabar Muslim identities and explores how the changing representations have reshaped societal perceptions and cultural values.

Ahnas Muhammed

Sugunan (Jagathy): Namaskaaram.

Tea Shop owner: Namaskaaram.

Sugunan: njangal chathiyankulangara devikshetra punarudharana committeekaara, ith mel shaanti – Subrahmanya shaastrikal [We’re Central Committee Members of Chathiyankulangaradevi Temple, this is our chief priest – Subrahmanya Shaastrikal].

Abu (Mamukkoya): Assalamu alaikum!

(Sekhar 55:14, 1990)

In the 1990 film Cherya Lokavum Valiya Manusyarum directed by Chandrasekharan, a group of friends(who are thieves), masquerading as members of a local temple committee, visit a local tea shop to solicit funds (Sekhar, 1990). Among them is Mamukkoya (Abu), who is introduced as the high priest, a representative of the Hindu community. However, this attempt at making money takes a comedic turn, when Mamukkoya inadvertently greets the people at the tea shop (in his Malabar accent) with “Assalamu alaikum,” a traditional Islamic greeting.

The portrayal of Mamukkoya’s character in Cherya Lokavum Valiya Manusyarum reflects how Malabar Mappilas are perceived as individuals bound by their religious and regional identities. Unable to transcend societal expectations, they are shown as individuals who lack intelligence. For example, in the scene described above, Abu’s greeting serves as a comedic device but it also highlights the naivety of characters from the Malabar region, propagating the stereotypical idea of the “Mandan Maappila”, which is also a colloquial usage that refers to Mappilas as persons who embody stupidity. By suggesting the foolishness of the Mappila, the scene indicates how they are unable to escape their Muslim identity. How might we make sense of such representations? In this article, I show how the concept of qualia and its indexical relationship with the medium of cinema can help understand the broader societal implications of such cinematic expressions vis a vis the evolution of the Mappila Identity in public consciousness.

The concept of ‘qualia,’ as discussed by Hankins (2013), emphasises the social construction of sensory experiences. It refers to the interpretative processes through which individuals assign meaning to sensory stimuli and shape their understanding of the world. In simpler terms, Qualia are like the colours and flavours of our experiences. They are the sensations, and feelings that make up our perception of the world around us. In the realm of cinema, qualia would refer to the sensory stimuli presented on screen. Although they are difficult to measure and are elusive to grasp as a physical object, one can trace qualia through the ways in which it make us assign significance to the visual and auditory cues that we receive.

For example, in the context of Mamukkoya’s dialogue in the film Cherya Lokavum Valya Manusyarum (1990), the qualia of being a Mappila is represented through a negative stereotype. Since the scene portrays Mappilas as simpletons, the portrayal perpetuates negative values such as backwardness, ignorance, and lack of sophistication vis a vis the Mappila community. From the viewer’s perspective, these sensory cues where the Mappila becomes the butt of a joke are then embedded into their collective consciousness where the scene amplifies the stereotype of the ‘mandan mappilla’ while circulating the qualia of the same among the audience.

In another Malayalam film, Manthra Mothiram (1997) directed by Sasi Sankar, there is a similar scene where the protagonist Kumaran, portrayed by Dileep, rehearses a scene from Kalidasa’s “Abhigyanashakuntalam” in a theatre (Sankar 10:15, 1997). In this scene, Kumaran takes on the role of King Dusyanta, while Abdukka, portrayed once again by Mamukkoya, plays the character of Maharshi. As the dialogue develops, Mamukkoya’s character delivers his lines in the distinct slang or style of the Mappila language instead of speaking in the style of the Maharshi.

Similar to the scene witnessed earlier, the inclusion of Mamukkoya’s Mappila-style delivery, contributes to the comedic impact of the performance. We see Kumaran reprimanding Abdukka for incorporating his Mappila language into the performance and expressing concern over the performance diluting the play’s authenticity. In response, Abdukka defends his choice, asserting that any Maharshi born in Malabar would naturally speak in the same manner.

Kumaran(as Dushyant): Avale oru vand vallaand shalyam cheyyunnuvallo. Nth? Ee thapovanathilum sthreekk peedanamo? [Am I witnessing that beautiful woman being harassed by a beetle? And that too in the vicinity of my presence?]

Abdukka(as Maharshi): Padachone! Band (Malabar slang for vand meaning beetle) enn paranjaa ejjaathi (again a Malabari expression of exclamation to denote the enormity of something) band. Athum onnum randum mattaano, path nappath band chernalle oru pennine peedippikkane. [Oh God! What an enormous beetle and that too attacking that hapless woman in clusters]

Kumaran: Nashippich! Ente abdookka ningal ithil Maharshiya alland Musaliyar alla. Mappila bhaasha paranj ee nadakam verthe kolam aakkaruth ketto. [Ruined it! For god’s sake Abdukka, you are a Maharshi and not a Musaliyar (Muslim clergyman), please don’t destroy this skit with your Mappila language] (Sankar 10:15, 1997).

Abdukka: Kumaara ninakk ee edayayi kurach vargeeyatha koodunnind, kalaakaranmaar thammil vargeeyathe paadilla. Malabaril eth Maharshi janichaalum engane parayollu [Kumaraa, you are getting very communal these days, there should never be no such things among artists. Any Maharshi born in Malabar would speak the same].

Along with the portrayal of Mappilas as simpletons, this scene also mobilises Mappila Malayalam to emphasise its disdain towards the particular community of speakers. Much like the categorisation of the ‘Mandan Mappila’, the filmmakers create a stereotype in relation to the language spoken by the Mappilas. Since the context involves the theatrical performance of a Hindu mythological story, it is interesting to see how the scene juxtaposes the figure of the Maharshi against the “Musaliyar” by indicating how the former requires a commitment towards speaking a pure standardised version of Malayalam.

This scene shows how language ideologies are also utilised towards crafting the sensory experience of the Mappila. Since the community has historically faced marginalization and discrimination, their language has also been consequently stigmatized and seen as undesirable (Kasim, 2018). These attitudes towards Mappila Malayalam are so entrenched as ‘commonsense’ that they can be easily deployed to produce humour at the expense of their identities. However, as Milroy (2011, 536) notes, “[c]ommonsensical attitudes are ideologically loaded attitudes, those who hold them do not see it in that way at all: they believe that their adverse judgements on persons who use language ‘incorrectly’ are purely linguistic judgements sanctioned by authorities on language” (Milroy 536, 2001). Adding to what Milroy said, it is my argument that such biases are constructed through the repeated circulation of qualia that emphasise the stigmatisation of Mappila Muslims.

Double Consciousness

The language ideologies dictating the prestige of linguistic variants within Kerala’s social fabric are deeply intertwined with the qualia experienced by the Mappila community. This dynamic perpetuates a form of double consciousness, wherein Mappila individuals are compelled to navigate between their own cultural and linguistic heritage and the broader societal perceptions influenced by dominant language ideologies. The Mappila language, acting as the “quali-sign”(that is a sign that represents a qualia) becomes, in Peircian terms, a ‘representamen’ of cultural inferiority, furthering negative stereotypes due to prevailing trends in the cinematic medium. This discrepancy between the perceived prestige of the Mappila language and its portrayal in media creates a dissonance in how Mappilas view themselves and how they are perceived by others, contributing to a sense of double marginalization or as Fanon puts it – the double conscious memory.

Double consciousness emerges when individuals view themselves through the lens of the dominant culture, adopting its values, norms, and prejudices as their own (Fanon). In doing so, they inadvertently validate their own subjugation, rationalizing and justifying their oppression. This can be illustrated through the experience of Salmanul Faris, an M.A student from IIT Gandhinagar, whom I interviewed. When asked about the prevailing stigmatization with respect to Mappila Muslims, Salman shared his perspective:

Whenever I was in a crowd or in a gathering, I always became conscious of my language. I remind myself repeatedly to not use my ‘Malappuram bhaasha”(bhaasha means language) because I have this inhibition that like, what if I am made fun of or not taken seriously. So I always switch registers while I’m talking with others. Even now I am not speaking the way I naturally do, although I know, these days it’s not that much of an issue but I’m so used to it now it’s almost like a default setting.

His conscious effort to avoid using his natural “Malappuram bhaasha” (language) in social settings reflects the internalization of negative ‘quali-signs’ associated with the ‘Mappila language’.

Code-switching: Avoiding Judgments

In this context, code-switching serves as a coping mechanism for individuals like Salman. Code-switching, broadly defined in linguistics, refers to the practice of alternating between two or more languages or dialects within a single conversation or interaction. This phenomenon is observed across diverse linguistic communities and is considered a natural aspect of language use. Speakers employ code-switching as a means to adapt their linguistic expression to different social contexts, often influenced by factors such as audience composition, setting, or topic of conversation. In Salman’s case, code-switching becomes a strategic tool to navigate social environments and preempt negative qualia judgments, as he opts for standard Malayalam over his local “Malappuram Bhasha”. While code-switching is not specific to any community, it is interesting to see how the alteration of linguistic codes is used to mitigate the risk of being subjected to ridicule. It is my argument that the act of code-switching is fundamentally connected with qualia, as it reflects the individual’s subjective/qualitative experience of linguistic discrimination and the internalization of societal norms. Salman’s reluctance to use his natural language for instance, suggests a heightened awareness towards the qualitative aspects of language and the perceived social consequences associated with its use. Films like Sibi Malayil’s His Highness Abdullah (1990), Priyadarshan’s Kilichundan Maambazham (2004), and many more exemplify this trend by projecting the caricatural versions of the Mappila as the Other.

In His Highness Abdullah (1990) for example, Abdullah (played by Mohanlal), is a qawwali singer who agrees to assassinate the Thampuran (King) for money. Disguised as Ananthan Namboothiri, he begins residing in the king’s palace and eventually has a change of heart. While Mohanlal carefully presents the upper-caste Hindu self to the Thampuran, Mamukkoya’s character, Jamal struggles with it. In one scene, when Abdullah introduces Jamal as Sankunni Nair to King Uday Varma, the king assumes that Sankunni Nair has come to retrieve Ananthan Namboothiri (Abdullah). When the Thampuran says that he has no intention of letting Ananthan go, Mamukkoya’s character, Jamal replies “Maanda,” a Malabar slang for “venda,” which means ‘no’ in Malayalam (Malayil 2:03:17, 1990). This sudden reply in an‘other’ slang baffles the King before Ananthan Namboothiri regains control of the situation.

King Udayvarma: Aara puthyaal?[Who’s the guest?]

Ananthan Namboothiri: Illathe kaaryasthanmaaril oraal aan, Sankunni Nair.[He’s one of the managers/stewards of our residence, Sankunni Nair]

King Udayvarma(to Sankunni Nair): Evdeya veedu? [Where are you from?]

Ananthan Namboothiri(intercepts): Illathin aduth thanneya.[Near my residence only].

King Udayvarma: Koottikkond pokan aano etheettillath? Iyaale ini illathekk vidanilla [Are you here to pick him back? I have no intentions of letting him go with you]

Sankunni Nair: Maanda [no need] (Malayil 2:03:17, 1990).

In scenes like this, where irony generates humour, it’s easy to overlook the deeper ideological implications at play. However, upon closer examination, such instances reveal the underlying ideological apparatuses shaping public perceptions. Like Ananthan, Sankunni Nair is expected to speak the ‘pure’ version of Malayalam. However, his response in Malabar slang creates a deviation that emphasises the negative qualia judgments against the Mappila community. This societal pressure compels individuals to internalise the stigma, leading them to adapt their behaviour, such as code-switching, in order to conform to societal norms.

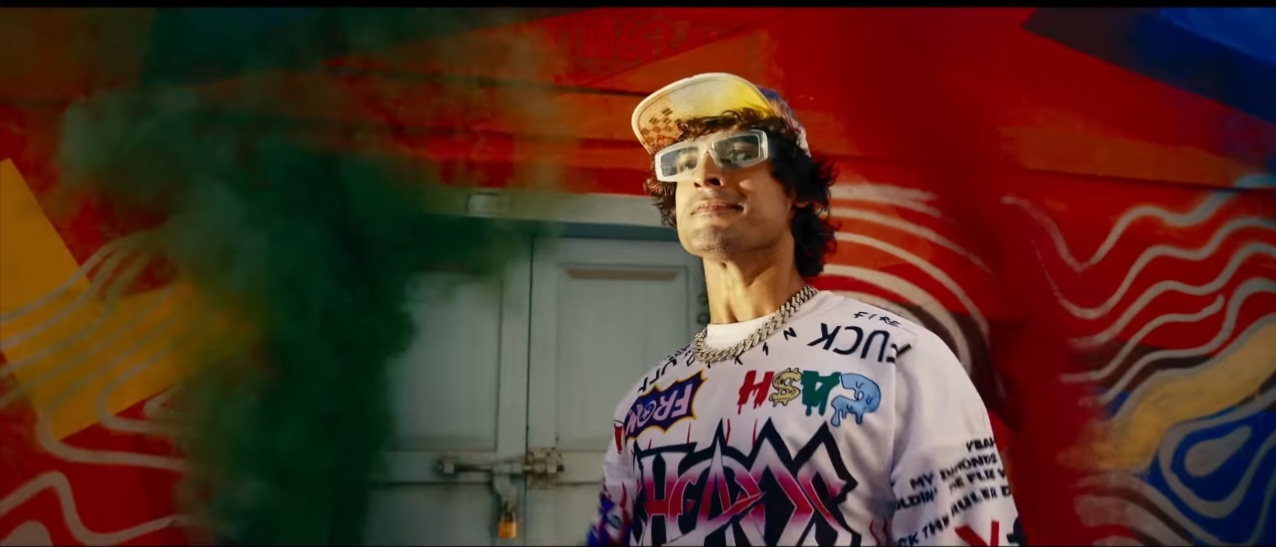

However, the recent cinematic landscape marks a significant reclaiming of Malabar Muslim identity, challenging stereotypes and fostering an authentic and empowered narrative. This transformation transcends cinema so much so that even Salman admits that the Malabar Bhasha “is not much of an issue these days”. The once-perceived deviant Mappila language is now embraced and considered fashionable, even among “standard” Malayali speakers. This shift can be traced back to films like Thattathin Marayathu(2012) and Usthad Hotel(2012) where a slightly more positive-value orientation could be seen in the depictions of Muslim characters although the movies persisted with regurgitating other negative qualia such as regressiveness standing for the Muslim father/ uncle etc. Nonetheless, in both movies, a sense of romance in the Mappila depiction emerges. This romance culminates in Khalid Rahman’s 2022 movie – Thallumaala, where the Malabar Muslim man becomes a youth icon.

The character Waseem in Khalid Rahman’s Thallumaala (2022) is a sought-after young man for his linguistic and stylistic outlook. One significant factor contributing to this shift may be the transition from the stereotypical portrayal of Mappila Muslim characters, often depicted by actors like Mamukkoya, to figures like Tovino Thomas, a renowned superstar of the industry. While Mamukkoya’s career was largely defined by typecasting, limiting him to roles that reinforced Mappila stock characters and stereotypes, Tovino Thomas’s (a non-Muslim) portrayal of Waseem, a stylish young Muslim man, challenges the negative qualia that were often circulated as Mappila characteristics. Furthermore, Mamukkoya, whose Muslim identity was often conflated with the stereotypical qualia of being a Malabar Muslim, Tovino’s casting represents a separation between the actor’s body and the mapping of the same onto the formulaic qualia of being a Mappila.

The actors’ identities and their qualitative relationship with the audience play a vital role, in shaping their public perceptions and influencing the portrayal of their on-screen characters and the associated qualia. Kasim justifies this assertion with the case of Mammootty. Mammootty, who rarely portrays Muslim characters and often assumes morally upright, upper-caste phallic hero roles embodies ‘the exceptionalness of Muslim masculinity’ (Kasim, 2018). In other words, he transcends his religious identity as a Muslim Other and becomes the Standard Malayali in public perception, while Mamukkoya’s characters reassert this Otherness. It is therefore crucial to acknowledge the dialectical and relational nature of the relationship between cinematic representations and the actors. Just as Mammootty’s on-screen ‘qualities,’ influenced his public perception as a trans-religious figure, Tovino’s off-screen ‘qualities’ as a superstar inevitably shaped his on-screen characters and the audience’s relationship with them. This means that both on-screen and off-screen ‘qualities’ affect the qualia judgments that further dictate the public’s relationship with the actors in relation to the characters they portray.

Another pivotal factor influencing the shift in the portrayal of Malabar characters lies in the positionalities of the directors themselves. Unlike outsiders whose perspectives may be informed by prevalent stereotypes, directors like Khalid Rahman, bring an authentic understanding of the Mappila community to their filmmaking. His portrayal of characters in the film defies existing stereotypes, showcasing Mappilas in a much more genuine and non-stereotypical light. Notably, the characters are depicted with a rich fashion sense, celebrating Mappila culture in its truest form. From religious practices to culinary traditions, from fashion sensibilities to everyday language, Rahman’s portrayal captures the details of Mappila life authentically. This departure from stereotypical representations marks a significant shift, contributing to a more nuanced and accurate depiction of the community, ultimately reshaping societal perceptions of Mappila Muslims.

The emergence of positive ‘quali-signs’ in cinematic representations portray more elaborate and empowered versions of Mappila characters, challenging stereotypes and fostering a genuine sense of authenticity. This positive reevaluation is driven by a shift in societal perceptions, wherein cinematic representations serve as a catalyst for changing attitudes and values. David Graeber (2001) emphasises the dynamic nature of value formation within societies, highlighting how values are contingent upon social interactions and can evolve over time based on changing cultural norms and perceptions. In the case of the Mappila language, its increased prestige reflects a broader reevaluation of cultural worth within Malayali society, influenced by cinematic representations that now celebrate the Mappila culture and identity. Muhsin Parari, the screenwriter and lyricist of Thallumaala confirms this shift and acknowledges the growing positive value transformation when he explains how Thallumala had helped in making the North Kerala dialect (Malabar Bhasha) carry ‘swag’ (Mathews, 2022).

The evolution of prestige associated with a language can be attributed to the shifting portrayals of both the language and its speakers within popular media. As media representations evolve, so too does the perceived ‘value’ of the language, directly influencing its desirability. This dynamic illustrates how cultural values are not static but are subject to changing cultural expressions and media representations.

Qualia, as the interpretative processes through which individuals assign meaning to sensory stimuli, plays a central role in shaping how cinematic representations are perceived and internalized. Through sensory engagement with cinema, individuals navigate cultural norms and negotiate their own perceptions, contributing to the dynamic construction of societal values. In the case of the Mappila language, cinematic and media portrayals have been instrumental in reshaping societal perceptions and reevaluating its cultural worth. As representations of Mappila Muslims become more detailed and empowered, the language gains increased prestige, reflecting broader shifts in societal values and cultural perceptions. It only seems fitting to conclude with a quote from Zizek, which, in my view, encapsulates the crux of the discussion. Zizek opines, “Cinema not only gives you what to desire but also tells you how to desire”(Fiennes, 2006).

References

- Boeck, M., & Rao, A. (2000). Introduction: Indigenous Models and Kinship Theories. In Indigenous Models and Kinship Theories. An Introduction to a South Asian Perspective (pp. 1–49). Berghahn Books.

- Fanon, Frantz. (1952). Black Skin, White Masks. Penguin Books.

- Fiennes, Sophie. (Director). (2006). A Pervert’s Guide to Cinema [English]. Channel 4 Television Corporation.

- Graeber, David. (2001). Toward an Anthropological Theory of Value : The False Coin of Our Own Dreams (pp. 1–21). Palgrave.

- Hankins, James D. (2013). An Ecology of Sensibility: The Politics of Scents and Stigma in Japan. Anthropological Theory, 13(1-2), 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463499613483397

- Ibrahim, Khalid. (Director). (2022). Thallumaala [Malayalam]. Central Pictures.

- Kasim, M. P. (2018). Mappila Muslim Masculinities. Men and Masculinities, 1097184X1880365. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184×18803658

- Mathews, Anna. “Muhsin Parari: North Kerala dialect has swag now, that is the satisfaction ‘Thallumaala’ gives me.” The Times of India. August 29, 2022.

- Milroy, James. (2001). Language Ideologies and the Consequences of Standardization. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 5(4), 530–555. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9481.00163

- Sankar, S. (Director). (1997). Manthramothiram [Malayalam]. Sania Pictures.

- Sekhar, C. (Director). (1990). Cherya Lokavum Valiya Manusyarum, [Malayalam]. Charangat.

About the Author: Ahnas Muhammed is a Junior Post-Graduate student pursuing a Masters in ‘Society and Culture’ from the Indian Institute of Technology, Gandhinagar. He completed his Bachelors in English (Hons.) from Hindu College, University of Delhi. His areas of interest include Lacanian Psychoanalysis, Political Theory, Cultural Anthropology, Football, Wrestling and so on.