The art of weaving grass mats is fast disappearing from a small village in Kerala, yet eight women weavers hold the fort against rapidly changing economic conditions. What is at stake in keeping alive an art form that seems to have outlived its times? Aswathy delves into this universal question by telling the story of the Killimangalam pulpaya and its makers.

Aswathy V

In 2004, Killimangalam, an idyllic village about 30 kilometres northeast of Kerala’s Thrissur district, gained international recognition. The reason was a humble grass mat, the Killimangalam pulpaya, which became an emblem of the village after it received the UNESCO’s Seal of Excellence. Despite the recognition, pulpaya weaving today is a dying art kept alive by a small but determined group of eight working-class women at the Killimangalam Pulpaya Neythu Co-operative Society. What makes them stay on in a vanishing profession? To answer this question, we need to delve into the history of the mats, and the lives of those who make them.

Making the Pulpaya

There is no documented record of when or where pulpaya neythu (grass mat weaving) arrived in Killimangalam. It is said to have come from Chittur in the Palakkad district or from Tamil Nadu, where korai grass weaving is a prominent craft tradition. The raw materials and techniques used in Killimangalam mats resemble the traditional Pattamadai 1 korai grass mats from Tamil Nadu.

In Killimangalam, korai grass is known as changnam or thottu muthenga. The fresh grass is first split into half, the pith (chooru) is removed, and then the grass is further split into four to six parts depending on the count required and the thickness of the grass. The strands are then immersed in running water for a day and dried in the hot sun.

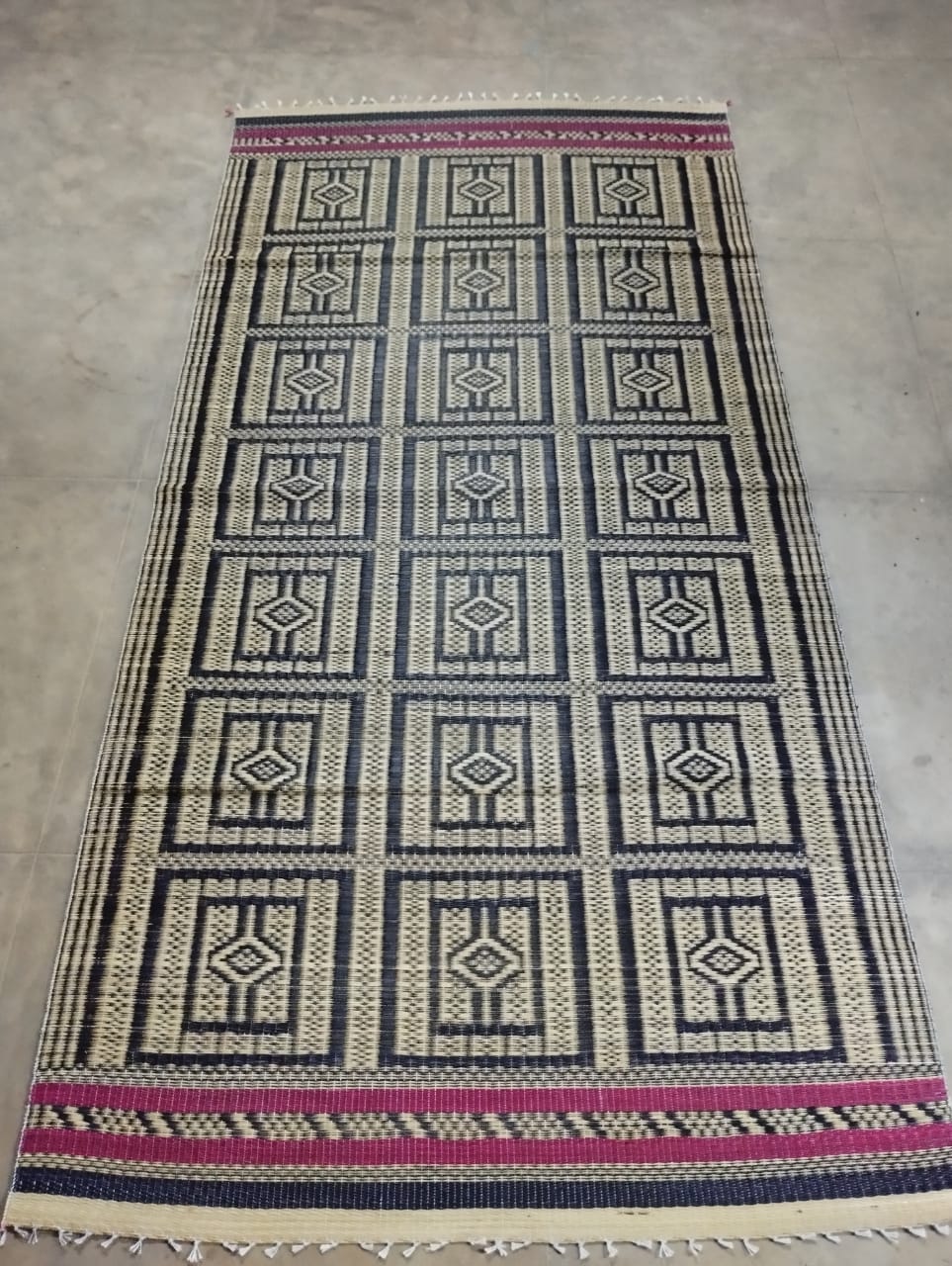

Well-seasoned grass turns white and is mostly used without dyeing. Since korai grass is not a very good absorber of water, the process of dyeing has to be repeated 2 or 3 times to achieve the desired shade. Though natural dyes were used traditionally, synthetic dyes are more in use today due to availability and low cost. The motifs and designs woven into the mats are inspired by objects seen in the surroundings, and some designs match the simple kara (hem design) of the neriyathu (light cotton) sarees. These include motifs such as the kannadi (mirror), valpoovu (stemmed flower), aanakannu (elephant eye), pallamkuzhi (a game board), and pallaku (palanquin).

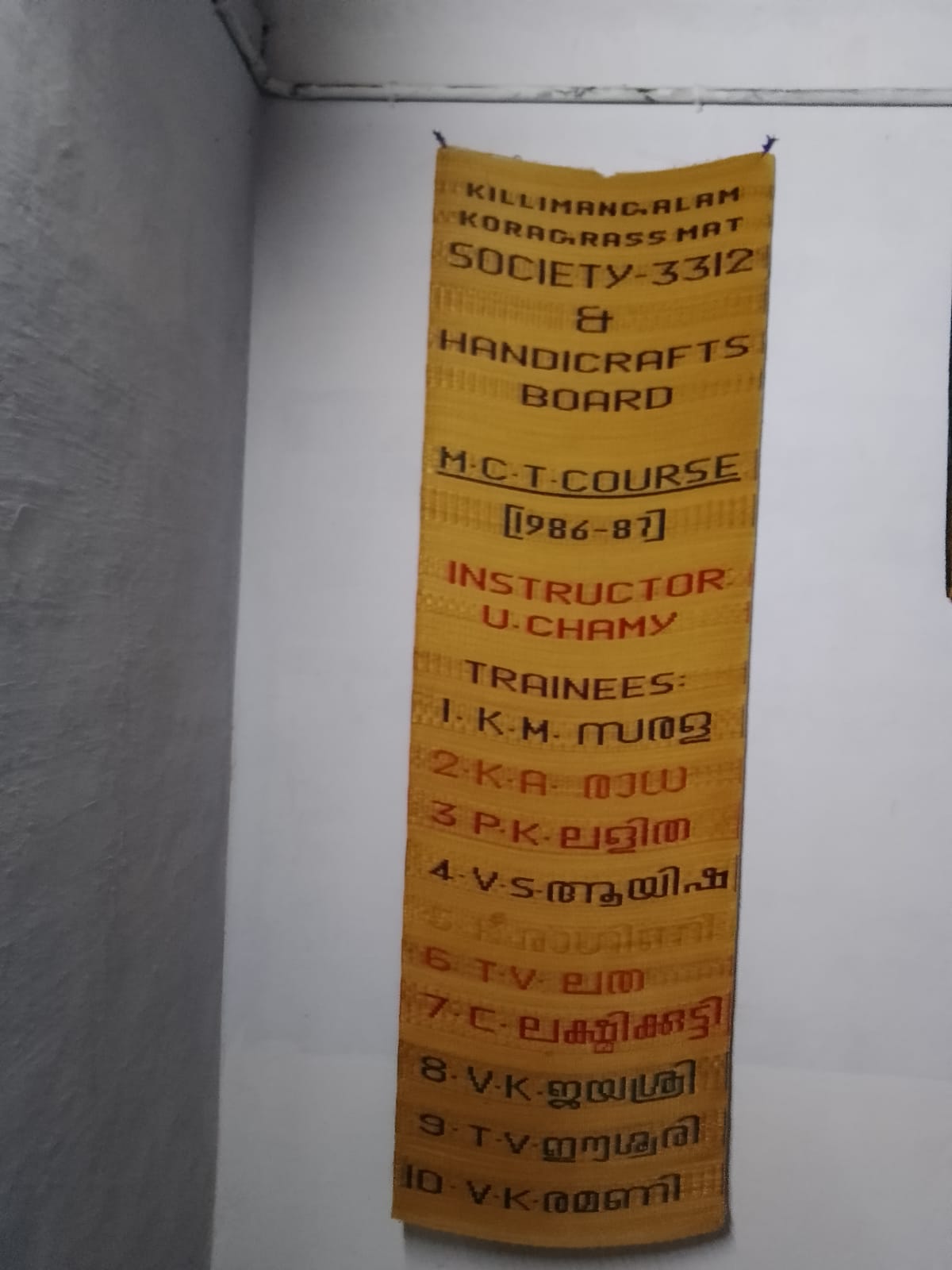

Korai grass mats are highly sought after for their cooling effect. If woven with superior quality grass that has reached the right maturity, these mats last a minimum of three decades. During my visits to the weaving society, I observed wall hangings that were crafted by weavers during training sessions conducted as early as 1987 and 1988.

In Kerala, these mats are the only ones woven using handlooms, making them unique. Furthermore, the process of creating korai grass mats is remarkably sustainable—it results in no wastage or by-products, thus presenting no challenges regarding disposal.

‘Your Mat is Made of Gold’ – Changing Times

In the past, mat weaving was a household activity that often involved all members in the family. However, when mat weaving was a family endeavour, even members with no experience would sometimes participate by cutting korai reeds or drying them to achieve their natural creamy-golden colour. The most challenging part of the process, however, was typically handled by more experienced weavers. In 1977, the Killimangalam Pulpaya Neythu Co-operative Society was started to collect products from household weaving.

Over the years, however, pulpaya weaving in Killimangalam has undergone a transformation along with India’s economy. Household weaving has now completely ceased, and the co-operative society, with its eight women weavers, each operating a loom, is now the sole location for this craft. This shift from home-based weaving to working solely at the cooperative indicates a declining interest in the craft, with no new individuals ready to take it up. During the era of home-based weaving, male weavers were present in the profession, but currently, Killimangalam mat weaving has become feminised, with no male weavers remaining in the field. Sudhakaran (59), the president of the co-operative society, remarked, ‘Men could not sustain a livelihood from mat weaving, as it does not offer regular work. They have moved to other occupations that provide a more consistent income, leaving mat weaving primarily in the hands of women’.

This transformation has caste-based aspects as well. Originally practised by people of the caste-oppressed Kurava community, mat weaving has expanded beyond its caste-specific origins to involve women from various religious groups—among the eight active weavers, not a single one is from the Kurava community. Sudhakaran (59), the president of the Society, explains that individuals from the Kurava community are now more educated and less inclined to pursue their ‘kulathozhil’2. A decade ago, when the Society was on the brink of shutting down, Sudhakaran stepped in to take charge, using his experiences to provide essential guidance to the weavers. Interestingly, Sudhakaran belongs to the Kurava community but his professional background lies in the healthcare sector and does not have experience in weaving. Nevertheless, Sudhakaran was involved in the co-operative society’s operations before becoming president, and his experience in society management aided in revitalising the Society on the edge of closure.

Among the weavers, four of them have been part of this tradition for 11 years, and the other four, newer to the craft, joined last year following a workshop which trained 30 women. These women work from Monday to Saturday, 10 am to 5 pm. The process of mat weaving is labour-intensive; with simpler designs taking about four days and more intricate ones up to nine days. Despite their hard work, the income is modest; if the mats are sold, each woman earns only about 5,000 rupees per month. Solely dependent on mat weaving, these women’s precarity results from a combination of expensive raw materials, lack of local demand, and competition from mass-produced goods.

When asked about selling their products locally, the weavers shared the villagers’ reaction: ‘Your mats are made of gold, so we do not want them’. The mats’ high cost, ranging from 2,350 to 9,000 rupees, positions them as luxury items primarily sold in distant, elite markets. The primary material, korai grass, sourced from Chittur at 300 rupees per kilogram, adds significantly to the cost. The weavers’ earnings are dependent on finding suitable markets, with a substantial stock of mats worth five lakh rupees awaiting sale.

Inquiring about their family support in light of the low wages and challenges in selling their products, I learned that many family members question the benefits of continuing in this craft. The weavers highlight that their family members often discuss other job opportunities that provide better financial security. Beena (44) said, ‘If I ask for financial help, my husband does provide it, but he then asks me, “Aren’t you a working woman? Then why are you asking money from me?”’.

Learning to Weave Differently

Weaving technology is a major aspect of the crisis that mat weaving is facing. During the era of home-based weaving, weavers used floor looms. However, frame looms were introduced to the society in 1977 by the Handicraft Council of India. The seating posture on the frame loom is less stressful compared to that on the floor loom. Though weaving on the frame loom reduces occupational hazards, it remains a time-consuming process, much like working with floor looms. The meticulous process, intrinsic to the quality and uniqueness of their mats, unfortunately limits the artisans’ capacity to meet large-scale demands. The Multi-Disciplinary Training Centre, operated by the Khadi and Village Industries Commission in Nadathara, Thrissur, has come up with a solution. The Centre has been providing training programs to the weavers, mainly to train them in weaving new designs and motifs for competing with the ever-evolving market demands. More significantly, the Centre has pioneered the development of a novel loom that incorporates pedals, significantly reducing the weaving time—what traditionally takes four days could now be accomplished in just a day and a half.

However, beyond the mechanics of weaving lies a deeper narrative around health and ergonomics. Years of weaving on traditional looms have left an imprint on the weavers, manifesting as eye, knee, and back ailments. The new loom developed at the centre addresses these concerns. It’s not just a ‘productive’ loom enhancing output; it’s an ergonomic marvel designed to alleviate physical strain. This loom, fostering better posture, reduces the toll on the weaver’s back, shoulders, and eyes, potentially transforming their weaving experience. Recently, the weavers have received training on this new loom, gradually opening up to its potential benefits.

However, the adoption of this new technology is a more nuanced matter than we might think, echoing the theories of Pierre Bourdieu and R. R. Wilk on naturalisation and comfort in the context of technological changes. As theorist Wilk notes (2001, 115), the idea of comfort is deeply rooted in shared understandings and physical perceptions, often operating subconsciously. For the weavers, comfort is not just about ease of use, but also about the familiarity and suitability of their traditional practices. After years of weaving, their routine has become a part of their identity, making the new and apparently labour-saving technology not uniformly perceived as comfortable or preferable. Sindhu (48), who is also the secretary of the Society, says ‘The new loom requires a huge financial investment. Our loom’s components are easily found at hand or can be quickly and cheaply repaired by local carpenters’. Indeed, the challenge of affordability for new looms is significant, as each loom, which can only be used by one weaver at a time, costs around five lakhs, which is a steep investment for weavers.

Geographic Indication (GI) – A Beacon of Hope

A painstaking manufacturing process and durability remain central to the value of the pulpayas, and to the identity of the weavers themselves. In a market of mass-produced replicas, however, it has become increasingly difficult to justify the cost of the pulpaya to buyers. Sandhya (33) recalls,

We went to an exhibition in Delhi. The customers thought we jacked up our prices just because we were at that exhibition. We took mats worth Rs. 3 lakhs, but all we sold was only about Rs. 5000. The good part was, the travel and accommodation cost for myself and Divya (41) was taken care of by exhibition authorities. At the GI pavilion, they had Madur grass mats which was bought by everyone. They cost like 1000 rupees each. But, you know, they make them with more cotton and less of that korai grass. If a cotton thread snaps, the whole thing can come apart. Our mats? We make them different. We use more grass, so they’re tougher. Even if a thread gives away, the mat’s still good. We could make ours like theirs to sell our products, but we don’t want to drop the quality of what we do. Our mats are strong, they last longer and don’t get ruined fast.

Clearly, the weavers deeply value the integrity of their craft. Their words reflect a steadfast refusal to compromise on quality for mere economic benefits. Sindhu encapsulates this sentiment: ‘If we start making mats of lesser quality, how can we still call them Killimangalam pulpaya?’

Confronted with the dilemma of retaining the essential nature of pulpaya weaving while also ensuring demand, the Society began considering the Geographical Indication (GI) tag. Geographical Indications are unique forms of intellectual property that certify products as being produced in a specific place, crucial for preserving local culture and aiding rural economies (Calboli 2013). This place could be a country, a region, or a locality where the goods’ distinct quality, reputation, or other unique characteristics are closely tied to their geographical origin.3.

Typically, however, legal experts charge fees that can amount to lakhs, creating a financial barrier that has hindered many potential GI products in India from achieving this status. Understanding this challenge, Saji Prabhakaran, Assistant Director at the Handicrafts Service Centre in Thrissur, brought these unique mats to the attention of the Textiles Committee under the Ministry of Textiles, Government of India. The Ministry stepped in to assist with the process, and the application was successfully submitted on April 10, 2023 to the government. The process can take up to two years, entailing stringent inspection. Once approved, GI status provides legal protection for the mats, safeguarding them against substandard replicas.

For the weavers, Geographical Indication (GI) status is not just about securing a legal right. Sindhu says, ‘We’ve been told by the authorities that if we get GI registration for our mats, it might help us reach international markets and bring in more money. We aren’t too sure about all that, but what we do know is, it may give us a good name. Getting GI means our mats are top-notch, and that’ll let everyone know we’re making quality stuff here’. As an alternative to compromising on quality, these weavers are also exploring the idea of diversifying their products, a strategy aimed at sustaining their weaving practices. Sindhu says, ‘we are planning to make items that require less grass, such as bags or clutches, people might be more inclined to spend on these than on mats’. This pragmatic approach signifies their adaptability in preserving their traditional craft amidst market changes.

This situation is deeply intertwined with issues of identity and the societal perceptions of certain types of work, particularly weaving. Today, weaving is often seen negatively, viewed as symbols of an old and struggling occupation in a fast-changing, modern world. As Sandra Wallman eloquently puts it, ‘work is as much about social transactions as it is about material production’ (1979, 1-2). Work shapes both the identity and the economy of the worker, transcending mere economic activity. For these weavers, their work is a personal experience, a relationship with the reality in which they live. Yet, this personal experience is constrained by the systemic logic within which they operate. Therefore, an analysis of work must consider which forms of labour are regarded as socially or morally worthy and fulfilling, either physically, spiritually, or intellectually. In the case of the Killimangalam mat weavers, their craft, rich in heritage and skill, faces the harsh realities of modern economic pressures and changing societal values.

The commitment of these women weavers to their craft even in the face of such pressures ensures that the traditional knowledge passed down through generations remains in safe hands. Yet, there’s an underlying concern: traditional knowledge faces the risk of disappearing without continual practice. The decline of numerous crafts due to this lapse in continuation highlights the precarious nature of cultural heritage. Looking forward, there’s a hope that even after fifty years, the Killimangalam Grass Mat Society will continue weaving, thereby keeping a rich tradition alive. Their story is not just about crafting mats; it’s about upholding a cultural legacy, emphasising the significance of preserving traditional crafts not only for economic purposes but also as an essential component of cultural identity.

References

Bourdieu, Pierre. and Richard Nice (trans.). 1990. The Logic of Practice. Stanford University Press.

Calboli, Irene. 2013. ‘Of Markets, Culture, and Terroir: The Unique Economic and Culture-Related Benefits of Geographical Indications of Origin’. In Research Handbook in International Intellectual Property, edited by Daniel Gervais, forthcoming. Edward Elgar, 2014.

Hughes, Justin. 2009. Coffee and Chocolate: Can We Help Developing Country Farmers through Geographical Indications. Washington, D.C.: International Intellectual Property Institute.

Lalitha, N., and Soumya Vinayan. 2019. Regional Products and Rural Livelihoods: A Study on Geographical Indications from India. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199489695.

Wallman, Sandra. 1979. Social Anthropology of Work. London: Academic Press.

Wilk, Richard R. 2001. ‘Towards an Anthropology of Needs’. Anthropological Perspectives on Technology, edited by M. B. Schiffer, 107-22. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

About the Author: Aswathy V. is a PhD scholar in Cultural Studies at Kerala Kalamandalam Deemed to be University for Art and Culture, Thrissur, Kerala. Her academic interests include medical sociology, sociology of culture, and intellectual property rights.

How do we buy the mat.