Ala speaks to Ruchi Chaturvedi, whose book, Violence of Democracy, published this year, draws on years of engagement with political violence in north Kerala to think about the forms of violence produced by the very practice of democracy.

1) Your book, looking at political violence between the ‘party Left’ and ‘Hindu right’ in Kerala, puts forth a fundamental argument–that democracy as we practice it today breeds its own form of violence. As you note, this runs counter to the popular belief, also supported by certain political philosophies, that by creating at least nominally equal grounds for different groups to compete for power, democracies inherently pave the way for less violent conflict. Can you tell us more about the idea of ‘the violence of democracy’ that you argue for in the book?

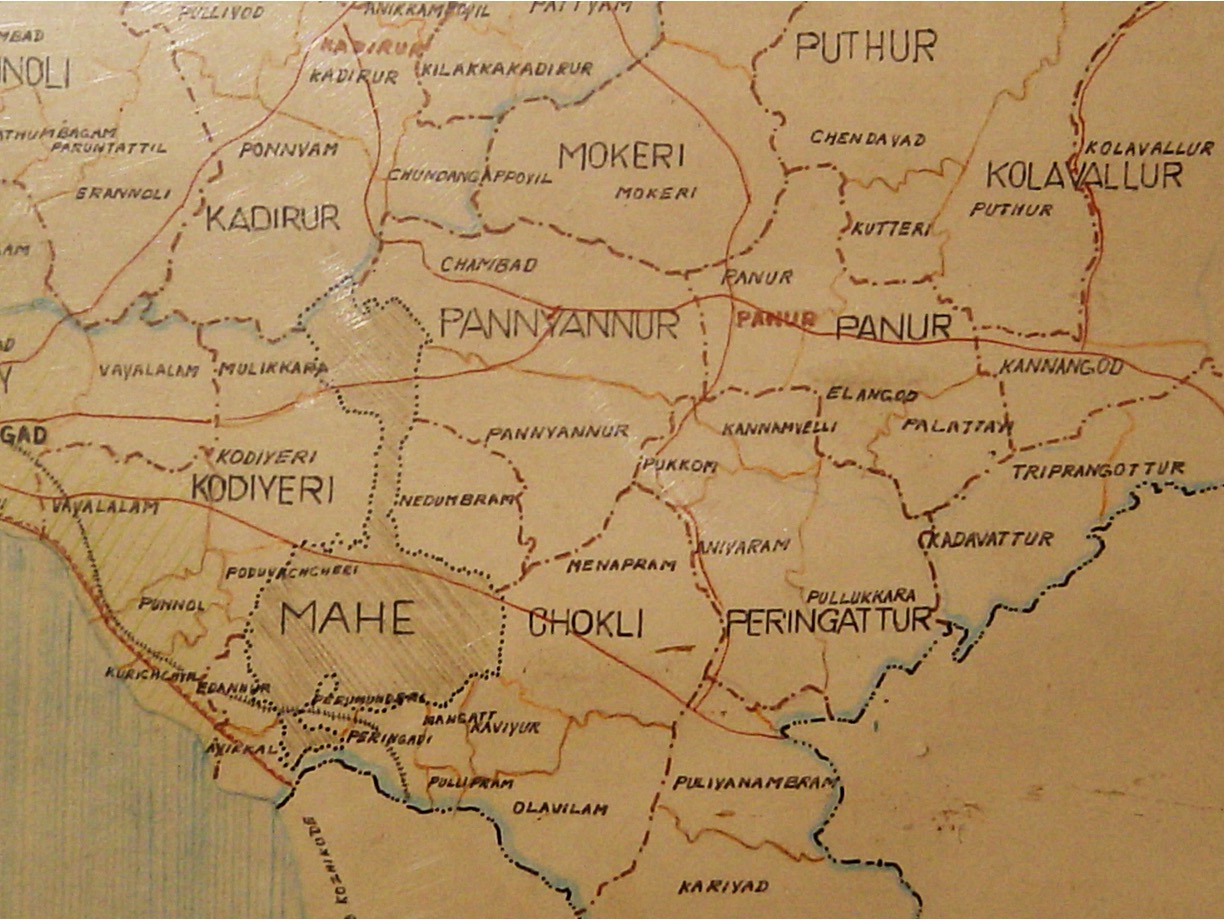

Longstanding violence between local-level workers of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) [CPI(M)] and the Rashtriya Swayam Sevak Sangh-Bharatiya Janata Party [RSS-BJP] combine is at the heart of my book. The book was long in the making; the question of similarities and difference between the violence of party workers on the left and the right compelled me to think about the larger political system that both of them inhabit. Indian democracy’s turn to violent majoritarianism has further informed the book’s overall argument.

When we look closely at the kinds of communities that CPI (M) and Hindu right-wing workers and supporters in Kannur have forged amongst themselves over the decades, we see the twin play of homogenisation and polarisation. In other words, we see the drive to create greater unity and affinity amongst those who are seen as one’s own, while sharply distinguishing (to the point of generating animosity) against those who are seen as opponents or competitors. This is a very basic feature of life not only amongst workers of the party left and Hindu right in North Kerala, but in many democracies across the world—in the so-called global south and in the Euro-American world.

In multiple parts of the world, competition for electoral and popular power has facilitated the drive to homogenise and polarise producing political communities violently opposed to one another. In some parts of the world such polarisation has occurred along ethnic lines, and in others along racial or religious lines. Ethnicised violence has marked elections in places as far ranging as Kenya and Sri Lanka. In the Euro-American world, white supremacist allies of European leaders such as Marine Le Pen, Eric Zenmour, and Donald Trump have enacted their own forms of symbolic as well as physical violence against immigrants and others. Divisiveness is the name of the game for the forms of politics that they enact. At the same time, these leaders and their political groups have won impressive electoral victories. My book takes seriously this relationship between ethnic conflagrations, majoritarianism, and xenophobia on the one hand, and democratic life on the other.

The history of interparty violence in Kannur that I plot over several decades enables me to identify the ways in which democratic competition creates conditions in which the impulse to contain the opposition turns into enmity and vengeful violence against the opposition. The conflict between CPI (M) and RSS-BJP workers is exceptional insofar as workers of the two groups are not divided along ethnic, caste, class or religious lines. But I argue that what that longstanding and frequently heinous conflict reveals are ways in which quotidian competition for support in representative democracies can, over time, generate intense violent conflict. I plot the career of that conflict and reflect on aspects that have driven the violence, particularly zeroing in on forms of communities that young men on the left and the right have come to forge amongst themselves, and the kinds of political masculinity they enact.

Hence even as the reader is taken through the details of the place and people who have enacted and suffered political violence in Kannur, those details become the lens through which we can comprehend how violence has been produced in democracies more generally.

2) One of the impressive feats of the book is that it seamlessly engages insights from subnational, national, and transnational contexts, countering the predominant tendency to exceptionalise Kerala as a region. Could you tell us how the site of Kannur, in northern Kerala, helped you or challenged you in this endeavour?

This is a very thought-provoking question that relates closely to the standpoint from which I ended up writing about interparty violence in Kannur. I grew up in north India; carrying out research in Kerala as a north Indian meant that I was always a national insider and a regional outsider. Furthermore, the book was revised and finalised in faraway South Africa. Navigating the insider-outsider status was part of the course while doing my research as it is for many anthropologists and sociologists. Writing about north Kerala in post-apartheid South Africa as it grapples with its own strengths and challenges as a democracy also influenced my perspective.

But where Kannur is concerned, I must note that a shared progressive ethos opened many doors. Many ordinary, thoughtful, politically conscious residents of the region concerned about the intense violence that the area has witnessed supported me. Amongst them were also people who were wary of explanations that reduce the violence that north Kerala has witnessed to its martial history. They were apprehensive about accounts that describe it as a deviant place.

I found that particularising and pathologising explanations resonated a lot more with administrators, scholars, and journalists living and working in other parts of Kerala or other parts of the country than those who reside in Kannur. The question that troubled people outside Kannur was, how could otherwise peaceful and broad-minded Kerala be witnessing egregious violence for years and years? For some of these people living in other parts of the state, Kannur was the place where you lose limbs and suffer grievous injuries, and where people are ‘hot-blooded’ and prone to feuds and vengeance.

I don’t discount the role that history of feuds and martial culture have played in producing interparty violence in Kannur, but this violence also resembles conflicts in other parts of the country and the world. The focus of my book is on those aspects of the violence in Kannur which can be understood by thinking through shared political inheritances, and the shared political system that we call democracy. At the same time, I have sought to be mindful of the specificities that have contributed to interparty violence in Kannur and made it stand out.

3) You talk about how the decades-long saga of tit-for-tat political violence between the party left and Hindu right in Kerala went relatively unnoticed nationally, until the 2010s, when the incumbent BJP government at the Centre began to highlight events in Kerala as part of its national strategies of legitimising itself by presenting an Other as a threat to Hindu culture and sovereignty. Today, invoking Kerala has become part of the BJPs political shorthand. Your research in Kannur, however, spans two decades, beginning in the early 2000s, and also takes a historical perspective from the partition era onwards. Can you see any differences between the period before and after the Sangh came into political power nationally?

As is widely known, the CPI (M) is the predominant electoral power in the state whereas the Hindu right has struggled to make an electoral dent in Kerala. Nevertheless, as others have also observed, strains of Islamophobia as well as what is called ‘soft Hindutva’ have taken hold amongst a range of groups including left affiliates. I have watched this turn in north Kerala with concern, albeit from afar.

There are parallels but also important differences between the post-emergency period and this current post-2014/2019 election period. In the post-Emergency period, the partnership between student wings of the Sangh and the struggle against corruption led by the freedom fighter and socialist leader Jayprakash Narayan helped the former to gain a level of acceptability and respect that it did not previously enjoy. Indira Gandhi’s crackdown on RSS cadres, and their imprisonment and ill-treatment during the emergency years made them appear as suffering martyrs in the eyes of many. In Kannur, this period saw supporters of the erstwhile Praja Socialist Party and its local leader P.R. Kurup join the Sangh formally and informally. The Sangh’s nationalism and its networks of mutual support had a particular draw for people who were wary of both the Communists and the Congress in the late 1970s and 1980s.

Currently, I believe the affinity with the Sangh is both stronger and more diffuse. It might not translate itself in the form of votes, but the effects of Sangh’s cultural and social engineering are visible in everyday suspicions and skepticism about Muslims as Others. These corrosive effects are visible in the ways in which people from a range of communities comfortably partake in global Islamophobia. Simultaneously, they seek to embody at least some aspects of a hegemonic Hindu identity. Such aspirations prevail even amongst those who have historically identified as secular and tended to the left. In these ways, I fear that Kerala too has taken a majoritarian and (dare I say) supremacist turn.

4)The spaces you explore—from autobiographies and biographies of political leaders to court battles around incidents of political violence to conversations with those who are part of this landscape—as you say, are dominated by young men, largely from non-dominant castes, and masculinist tropes of political engagement. What was your experience of ethnographic research for this book? Could you tell us something about the dynamics of caste and gender that you noted?

At the outset, my research on CPI (M) and RSS-BJP violence in Kannur entailed identifying those who had experienced and enacted the violence on both sides of the political divide and discussing its character and history with them. At the same time, I sought to obtain and review all the court documents that I could about violent incidents involving members of the two groups as well as other political parties. As trial dates of cases that I was following came up, I was in courtrooms to observe how blame was apportioned and criminal law practiced in cases of political violence at the district court-level. Forging a rapport with party left and Hindu right-wing workers, local-level party leaders, as well as court officials and lawyers was crucial for all these activities.

There are many layers of my ethnographic encounters that I believe I can unpack more. I am mindful that RSS-BJP leaders viewed me with favor due to my ‘upper-caste’ name. At the same time, my secularised identity and association with anti-Hindutva movements won favor with CPI (M) members. But beyond these questions of identity and affinities, over time, I found myself cultivating a sympathetic ear and disposition towards local-level workers of both groups with the indispensable help of my research assistant.

Several workers of both groups who became my key interlocutors belonged to so-called backward castes (mostly Thiyya) surviving on living-wage from blue-collar work. In several households, women were the main breadwinners of the families. Some of them worked as anganwadi or health-care workers in state-run facilities. In fact, the women’s support and labour made it possible for male members of the household to carry on their political work. It enabled the men to forge their community of comrades. A number of women belonging to CPI (M) and Hindu right-wing affiliated families enjoyed relatively equal access to livelihood and income, but their identities remained subsumed within their families. Such women’s participation in public and party-related spaces were mediated by the men in their families.

For young men from poor households, their respective party networks made up an infrastructure of care. Party networks had turned into kin-like associations for them through which small benefits like a hospital bed at the time of a health emergency, or loan from village panchayath to repair a roof became available. I describe the political valence of these circuits of care in several chapters. Party networks were also mobilised to defend local-level workers when they were prosecuted for various acts of violence. By the same token, such care made individual party members vulnerable and dependent on their respective party networks.

Members of the CPI (M) as well as the Hindu right who I interacted with had suffered violent attacks as well as participated in them. In many cases, participation in acts of violence had intensified party workers’ vulnerability. Long running trials were stressful for them and their families. Several young party workers of the left and the right preferred to discuss that stress and their encounters with violence away from the eyes of their families. Aware of that, I too maintained some distance from their parents, wives, sisters and children. Hence the young male party workers rather than their families remain the primary focus of my book.

Young men belonging to both groups performed aggressive political masculinity in several contexts, whereas in other contexts this masculinity was fragile. Questions of the workers’ culpability were being raised in several spheres—some time in covert whispers and sometimes overtly through criminal charges and trials. The ways in which members of the two groups dealt with issues of culpability, and their sense of vulnerability is a topic that I discuss at length in one of the chapters of the book.

The workers’ close association with kin-like party networks had impelled their violence; they had also suffered it. And their violence had opened them to criminal charges, long trials, imprisonment and even the death penalty. All this weighed heavily on many members of both groups.

I believe workers of the two groups shared their sense of precarity and vulnerability with me, in part, because as an outsider and a woman, I was seen as bearing my own strengths and vulnerabilities. This made it possible for party workers on the left and the right to share their predicaments with me and my research assistant. For most part, these young men of the party left and Hindu right did not regard me with suspicion or reprehension. But at the point that I felt that this began to happen, I ceased my ethnographic research and turned to archival and published materials.

About the Author: Ruchi Chaturvedi is Associate Professor at the department of Sociology, University of Cape Town, South Africa. She is a political and legal anthropologist who works on cultures of democracy, popular politics and political violence in postcolonial democracies. She received her PhD in Anthropology from Columbia University. She is the author of Violence of Democracy: Inter-party conflict in South India, which was published by Duke University Press and Orient BlackSwan in 2023.

Insightful conversation. Thanks, Ala, for a sneak peak of the key points made by Chaturvedi’s important work.