Was foreign soap a luxury product or an everyday commodity in early twentieth-century Kerala? Greeshma Justin John follows the interesting history of soap as a commodity at this time, examining how it became a popular staple commodity in the region.

Greeshma Justin John

മേൽപ്പറ്റിടും പൊടി,യഴുക്കു, മെഴുക്കു, നാറ്റം

വേർപ്പെന്നുതൊട്ടവ കളഞ്ഞതിശുദ്ധിയാക്കി,

വായ്പ്പേറിടും തനുസുഖം മനുജർക്കു ചേർപ്പാൻ

സോപ്പേ, നിനക്കു ശരി വാസനയേതിനുള്ളൂ. 1

This ode to toilet soap, so to speak, appeared as an advertisement in Kavana Kaumudi, the celebrated early-twentieth-century verse magazine (Priyadarsanan 1971). The convergence of the advert and the poem, at a time when parishkaram2 had been receiving intense traditionalist critique, aptly mirrors the traction soap was gaining among the literati, if not the broader Malayali middle classes they belonged to. However, this article goes beyond the middle classes and makes a case for the participation of ‘the poor’ in shaping the trends and patterns of consumption in early-twentieth-century Keralam.3 It challenges the view that consumption, especially of things not regarded as the bare necessities of life, was insignificant in the lives of a populace impoverished by colonialism. As a fertile site to understand the mechanism of power in society, including its creation, continuation, and contestation, consumption assumes centrality in social life (Haynes and McGowan 2010).

Modern, industrially produced toilet soap is a commodity that could effectively demonstrate the working of power in early twentieth-century Malayali society. For one thing, the habit of daily bathing with soap is baked into the idea of the quintessential Malayali, often bolstering debatable claims of regional exceptionalism in cleanliness (Zacharia 1977; Fig 1 shows soap companies employing such claims). Moreover, as I have argued elsewhere, soap itself became a thing of power with which individuals and groups negotiated their social locations within the matrix of caste, class, and gender power in Keralam. While this article highlights the power dynamics intrinsic to consumption by poorer social groups, it also emphasises their role in imparting a distinct character to the Malayali reception of soap in the subcontinent. But first, let us analyse certain features of the region’s nascent soap industry that contributed to these trends and patterns.

‘Standard’ versus ‘Spurious’ Soaps

As vegetable oils replaced tallow (sheep and cattle fat) as the chief ingredient of soap in the late-nineteenth century (Alsberg and Taylor 1928), Keralam, with a physical geography conducive to the cultivation of oil seeds, secured a spot on the map of the global soap trade. A group of Malayali soap entrepreneurs, eager to take advantage of the shift, arose in the early twentieth century. In a few years, soap makers of diverse scales, utilising varied production techniques, ingredients, and marketing strategies, materialised in the soap production landscape of the region. We can broadly classify the emergent cluster of soap manufacturers into two: the first network relied on colonial and princely governmental investments in the soap industry, viz., technical know-how and training, loans, and other inputs. Most of these manufacturers belonged to dominant social groups, possessing adequately modern scientific knowledge to acquire training and sufficient capital to launch businesses of scale and sophistication mandated by colonial standards. In contrast, the second set of soap makers primarily operated cottage-scale concerns. Hailing from relatively heterogenous social backgrounds, these small-scale manufacturers drew on alternate nodes of knowledge transfer,4 different from and often in opposition to colonial soap manufacturing networks.

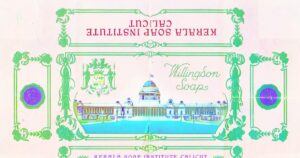

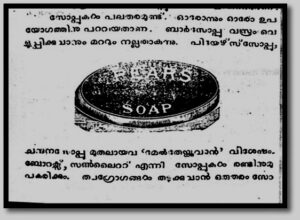

The contrast between the two soap production networks was stark in terms of manufacturing processes. Around 1924, the Government of Madras issued a standard manufacturing formula for soap. But only the Kerala Soap Institute (KSI hereafter), the government factory-cum-laboratory set up in Kozhikode in 1917, could afford the largely mechanised boiled-process required to make milled, ‘high-class’ toilet soaps in Keralam during the early 1920s (see Fig 2). Although firms that could adhere to colonial standards surfaced since, they were few and far between. In this scenario, the mechanised production process became a guarantor of soap quality (see Fig 3). However, most cottage-scale companies employed the cold-process method whereby soaps could be produced manually, at room temperature, and with minimum equipment. The manufacturers utilised readily accessible ingredients such as vegetable oils and locally sourced alkaline substitutes like cadjan ashes and neettu kakka (quicklime obtained by heating clamshells). In colonial evaluations, these processes were crude, and their soaps, adulterated.

made’ (and hence) ‘foreign-quality’ toilet soaps and the twelve-ounce Golden laundry-cum-toilet brand. The company claimed that its products adhered to rigorous chemical standards and were safe for skin and clothes (Sreemathi Special Issue 1934, Appan

Thampuran Library, Thrissur)

If soaps of large-scale companies were more likely sold through established merchants and stores, cottage soaps depended on less formal trade networks. An example is the itinerant vendor of cosmetic products, who announced her arrival with the signature melodic call, ‘soap, cheep, kannadi’ (soap, comb, looking-glass). Moreover, cottage firms mimicked the better-known brands’ names, labelling, colouring, and packaging techniques. Consequently, an opposition materialised between the so-called standard/ pure/ quality soaps and substandard/ spurious/ imitation soaps. This binary influenced consumption choices, especially of the Malayali middle classes emerging at the turn of the century.

The Middle Classes and Soap

In the 1890s, the lower strata of the dominant castes, especially the Nairs, constituted the modernising middle classes in Keralam. By the early twentieth century, the upwardly mobile sections of the subjugated castes, including the Thiyyas and the Ezhavas joined the rank (Sreejith 2021). They were essentially a consuming class, often inspiring parishkari stereotypes, and subscribed to colonial notions of quality. The foreign provenance of the goods they acquired seemed to lend an added sheen to consumption. Hence, the middle classes would rank Bilathi (English) soaps a notch above locally produced ones, as writer Murkoth Kunhappa (1905-1993) relates in his childhood recollection (Kunhappa 1950).

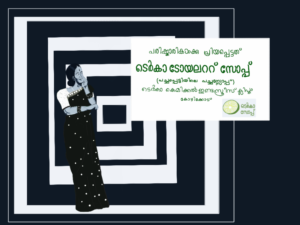

Of the many popular foreign (especially English) soap brands in early-twentieth-century Keralam, Pears’ Glycerine enjoyed considerable popularity. Malayalam journals of the time would list Pears’ as a quality product (Nambi 1907). The penchant for the brand lingered among the middle classes even at the peak of the Swadeshi Movement. So much so that when the brand faced Swadeshi backlash elsewhere in the subcontinent, a Malayalam school textbook from the princely state of Cochin was nonchalant about carrying an image of a Pears’ cake in a lesson on soap (see Fig 4). While this pattern of middle-class consumption was a pan-subcontinental phenomenon, a pivotal shift in the region’s engagement with the commodity happened as ‘the poor’ embraced soaps in their everyday life.

Soap and the Sadhukkal

Sources varying from periodicals, archival documents, and advertisements suggest that the poorer classes had access to toilet soap at the beginning of the twentieth century. Middle-class commentators routinely recorded apprehensions about soap’s quality in Malayalam periodicals, particularly those consumed by the sadhukkal (literally, ‘powerless people’/ ‘the poor’) and sadharana janangal (‘the commonfolk’). An early observer criticised that the sadharana janangal purchased soaps by price and scent rather than quality (MNPK 1905). Almost the same sentiments echoed three decades later when another writer noted that the sadhukkal risked their health by consuming cheap, substandard soaps (Warrier 1937). A related complaint was the apparently commonplace use of laundry soaps for toilet purposes (Menon 1907). The colonial officials attributed this habit to ‘the poor’ (KSI 1927). The frequency of such narratives throughout the early twentieth century suggests that the poorer classes persisted in the use of ‘cheap’ and ‘substandard’ soaps for toilet purposes despite the many cautionary tales directed at them.

While thrift behaviour cannot limit itself to the poorer classes, we have clear hints of the emergence of an alternate perception of soap as a mass commodity, at least among soap companies. Towards the late 1920s, KSI documented a trend favouring ‘durable’, scented soaps over lathering and ‘wasteful’ soaps (Bazl-Ul-Lah 1926). This was also when soap companies began to identify the poorer groups as a valuable consumer segment, and even firms with ‘high-class’ clientele introduced strategies tailormade to absorb new customers. The production of laundry-cum-toilet soaps is a case in point, KSI’s Washwell Soap and Lever’s Sunlight being specific examples (Fig 3 & 5 feature multipurpose soaps by smaller brands). The sale of soaps in various dimensions, such as half/quarter cake, loose chips, and scraps, was another strategy.

Furthermore, companies began to market soap as an affordable commodity. For example, Kozhikode-based Techno Chemical Industries Ltd advertised that its soaps were appreciated across ‘the proletarian-capitalist divide’.5 The Iyyappen Soap Works from Thrissur claimed that its products could be used ‘from huts to palaces’. Although the firm resorted to class stereotyping (the parsimonious poor versus the tasteful rich) while promoting its soaps: ‘Iyyappen’s soaps are affordable enough for the sadhukkal and superior enough for the sambannar (the rich)’, declared an advertisement appearing, curiously enough, in a socialist newspaper (Fig 5).

Spurious Stereotypes?

So, what do we make of the narratives of colonial officials, middle-class Malayalees and advertisers who recount their impressions of the nature of soap consumption by ‘the poor’? We could suppose that far from being a ‘tasteless lot’, the sadhukkal, most of whom were also the sadharanakkar, stubbornly charted a consumption trajectory of their own. In consuming products of appealing colours, perfumes and packaging, although of plausibly questionable quality, the sadhukkal were as much the connoisseurs of soap as the sambannar. While the middle classes patronised the more expensive poo-chaappa (flower-mark) and mana/ vaasana (scented) brands befitting colonial standards, the poorer classes chose soaps that remained within their budgets but also catered to their aesthetics. These included the numerous cottage products and imported Japanese soaps that flooded markets of the Madras Presidency in the 1930s.

An additional question pertains to the composition of the abstract category, ‘the poor’. The multiple registers of the Malayalam word sadhukkal could offer a clue. Apart from connoting powerless and economically impoverished groups, sadhukkal denoted ‘untouchable’ castes, especially the Dalits, in the early twentieth century.6 Given the complexity of caste power, a substantial proportion of the poor occupied the lower tiers of the caste hierarchy as well. The Dalit and other anti-caste leaders precisely addressed the interface of caste oppression and economic deprivation while popularising soap in their constituencies. Soap became part of a new corporeal order they envisioned, at once promising liberation from subjugation and social mobility. The radical potential of soap could have been what the dominant social groups reckoned when they restricted subjugated castes from accessing ‘quality soaps’ in Malabar in the period.7 The emphatic endorsement of soap by anti-caste leaders, therefore, inducted the poorer castes as active agents in the early-twentieth-century consumption culture of Keralam.

Further, the poorer castes altered Malayali soap consumption patterns, as inferred from the region’s distinctive response to specific consumer trends (John 2023, 148–49). For instance, early-twentieth-century Keralam remained an exception to the pan-subcontinental trend favouring vegetable oil soaps vis-à-vis tallow soaps.8 The parishkari impulses of the middle classes surpassing caste-based aversion for tallow soaps formed only one strand of the phenomenon.9 Equally relevant was the lack of ritual abhorrence the subjugated castes shared with the region’s significant Christian and Muslim population.10 Similarly, Malayalis held a largely dispassionate attitude towards Swadeshi soaps during much of the early twentieth century. While the allure Bilathi soaps held for the middle classes partly explains the trend, the patronage of Japanese soaps and imitations of other imported products by the poorer classes played no less a part. The magnitude and resilience of the consumption pattern of the poorer class, elite criticism notwithstanding, cut into the profits of large-scale soap manufacturers. KSI, for example, incurred heavy losses throughout the 1920s and the 1930s, thanks to Japanese soaps and the ‘ridiculously low-priced coloured imitations’.11 The accommodation of ‘mass’ tastes, therefore, became imperative for larger-scale soap manufacturers to keep their boats afloat in early-twentieth-century Keralam.

The poorer classes and castes were thus instrumental in widening the consumer base of soap in early-twentieth-century Keralam and its subsequent popularisation in the region. With their characteristic responses to vegetable oil soaps and Swadeshi soaps in the early twentieth century, the poorer social groups also played an equally pertinent role alongside the middle classes in actively (re)fashioning a consumption culture around the commodity. The particular patterns of soap’s use by ‘the poor’, therefore, infused a unique flavour to consumption in Keralam.

References:

- Alsberg, Carl L, and Alonzo E Taylor. 1928. Fats and Oils: A General View. California: Food Research Institute and Committee on Russian Research of the Hoover War Library.

- Bazl-Ul-Lah, Muhammad. 1926. ‘Report of the Department of Industries, Madras 1926’.

- ‘Census of India, 1931—Travancore’. 1932. Trivandrum: Government Press.

- Haynes, Douglas E, and Abigail McGowan. 2010. ‘Introduction’. In Towards a History of Consumption in South Asia, edited by Douglas E Haynes, Abigail McGowan, Tirthankar Roy, and Haruka Yanagisawa, 1st ed., 1–25. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- John, Greeshma Justin. 2023. ‘“The All-Cleansing Soap”? History of Soap in Keralam c. 1880–1950’. In Histories of Health and Materiality in the Indian Ocean World: Medicine, Material Culture and Trade, 1600–2000, edited by Burton Cleetus and Anne Gerritsen, 1st ed., 145–70. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- ‘Kerala Soap Institute—Training of Apprentices—Regarding’. 1927. Madras Records.

- Kunhappa, Murkoth. 1950. ‘Soap’. Mathrubhumi Weekly, April 1950.

- Menon, Karat Achyutha. 1907. ‘Sthreedharmam’. Lakshmibai, Vrishchikam 1907.

- MNPK. 1905. ‘Orapeksha’. Dhanwantari, Karkidakam 1905.

- Nambi, T Narayana. 1907. ‘Thechukuli’. Dhanwantari, Karkidakam 1907.

- Priyadarsanan, G. 1971. Manmaranja Masikakal. 1st ed. Kottayam: Sahitya Pravarthaka Co-operative Society ltd.

- Sreejith K. 2021. The Middle Class in Colonial Malabar: A Social History. 1st ed. New Delhi: Manohar Publishers & Distributors.

- Warrier, P V Krishna. 1937. ‘Abhyanga Snanam’. Mathrubhumi Weekly, April 1937.

- Zacharia, Paul. 1977. ‘Malayaliyude Mayalokam’. Kalakaumudi, April 1977.

Author bio: Greeshma is a research scholar working on the history of cleanliness in Kerala. You

can reach her at greeshmahcu@gmail.com.

Acknowledgement: Thanks to Dr. Arvind S. Susarla for critical inputs that helped clarify some

of the ideas discussed here. Usual disclaimers apply.