Pulp fiction in Kerala remains a genre that does not receive much attention, despite the significant role it has played in cultivating a reading culture in Kerala. Serialised novels in Malayalam weeklies had readers hooked for decades. Shibu B S delves into the rich world of painkili (‘songbird’) novels in Kerala.

Shibu B S

പള്ളിപിരിഞ്ഞ് ആളുകൾ പോയിത്തുടങ്ങി. നിമിഷങ്ങൾ കഴിഞ്ഞു. വളഞ്ഞുപുളഞ്ഞ കൂപ്പ് റോഡിലൂടെ സെലീന വരുന്നത് ദാവീദ് കണ്ടൂ. ഒരു മാലാഖയെപോലെ തോന്നി അവന്. സൗന്ദര്യദേവതയുടെ അംഗ വടിവുള്ളവൾ. വെളുത്ത് തുടുത്ത മുഖം. കാന്തിചിന്നുന്ന കാന്തകണ്ണുകൾ. തുടുത്തുചുവന്ന ചുണ്ടിണകൾ. ഈറ്റക്കാനത്തെ ധനാഢ്യരുടെ പലരുടെയും ഉറക്കംകെടുത്തുന്ന സൗന്ദര്യധാമം ആണവൾ.

The church dispersed and people began to leave. Time passed. David saw Selina coming down the winding forest road. She appeared angel-like to him. She had the figure of the goddess of beauty. A fair and radiant face. Sparkling, inviting eyes. Full red lips. She was the beauty that disrupted the sleep of many wealthy men of Eettakkanam.1

– Manasakshikodathi, Josey Vagamattom

A popular pulp fiction narrative of the 1980s would have begun thus and gone on to narrate the tale of an intense love or a strong family relationship, an intriguing fight between a modest hero and a strong villain, or the cause of a mysterious murder. The authors, with their lucid style, lured readers who literally snatched the weeklies from the pawn shops and finished the novels in one go. Manasakshikodathi [The Court of Conscience], one of the superhit novels that was serialised in Malayala Manorama weekly in the 1988-89 period, narrated the rivalry between David and Elias. The cast of characters—Rennichan, Celina, Kuttiyamma, and Mini—were all familiar to families in Kerala. So were hundreds of others.

Pulp fiction, a genre that is not often talked about, helped nurture a reading culture among Malayalis. It became so popular in the 1980s and 90s that the collective circulation of the weeklies featuring pulp fiction novels skyrocketed at this time. As someone who grew up being an avid reader of the genre, I dove into my personal collection of pulp fiction novels, drew from the personal archives of others, and spoke to people from the pulp fiction industry to understand more about this genre and its history.

Chapter 1: A Painkili Tale

The origin of pulp fiction in Kerala dates back to the 1950s, when Malayalam literature dealt largely with the people and culture of Valluvanad, an erstwhile chiefdom in present-day central Kerala that persists as a strong regional imaginary. It was the late writer Muttathu Varkey who pioneered a parallel stream in Malayalam with Ina Pravukal (Pigeon Mates, 1953). His second novel Paadatha Painkili (The Songbird That Never Sang, 1955), modelled somewhat on Mills & Boon novels and similar romantic fiction in the Western world, marked the birth of painkili [songbird] literature. Serialised painkili novels also led weeklies like Mangalam, Manorama, and Manorajyam from Kottayam and the rest of central Kerala to shoot into prominence. They were somewhat derisively referred to as ‘Ma’ magazines, alluding to their first letters. Soon, many new writers came up with pulp novels which narrated the lives of the common man. Along with the love story of Narayanan Nair and Narayaniyamma—set against the backdrop of the Valluvanadan Bharathapuzha—in an elite magazine, readers started embracing Meenachilar-based Anthony and his lover Rahel.

E J Kanam, Muttathu Varkey, and Chembil John were the most popular trio of pulp fictionists of the 1950s and 60s. Kanam’s Pampanadi Panjozhukunnu, Kalavarsham [Monsoon], Navarathri [The Ninth Night], Nishadam [The Seventh Note], and Chembil John’s Veenayil Urangum Ragam [The Tune Asleep in The Veena], Chuzhikal Malarikal [Whirls and Eddies], Swapnalekha, and Murappennu [The Betrothed] were all big hits of that time.

After the trio, it was the turn of Moythu Padiyath and Vallachira Madhavan to enthral the common men with their romantic tales. Madhavan’s Churulmudikkari [The Curly-Haired One], Yuddhabhoomi [Battlefield], Chuvanna Sandhyakal [Rosy Evenings] and Edenile Aa Shokarathri Veendum [That Mournful Night of Eden, Again] were some of the most popular novels of the 1970s. In between, R P Menon, who wrote under the name Pamman, came up with his tales of love, adding a pinch of erotica to them. Pamman’s novels were bestsellers, and a few of them, like Chattakkari [The Shrew] and Adimakal [Slaves], were made into movies. Ayyaneth was another popular writer of that time, while John Alunkal and Johnson Pulinkunnu made a mark in the early 1980s.

By then, the number of ‘Ma’ magazines based in Kottayam rose to nine, and more young writers forayed into the scene. Joycy, Sudhakar Mangalodayam, Mathew Mattom, M D Ajayaghosh, K K Sudhakaran, Murali Nellanad, and women writers including Mallika Younis, Kamala Govind, M D Ratnamma, and Chandrakala S Kammath became the most sought-after pulp fiction writers of the 80s and 90s.

Writer K K Sudhakaran doubted whether the writers of pulp fiction got adequate recognition. ‘Though the common man reads these novels, elite readers, editors and award committees usually neglect the Ma magazine writers. In my honest opinion, pulp fiction has helped improve the reading habits of a Malayali’, he told me.

Chapter 2: The Joycy Saga

Joycy, who rose to popularity in the 80s and 90s, has undoubtedly been the superstar among his peers. He used three pen names—Joycy for serious fiction, Josey Vagamattom for crime and action thrillers, and C V Nirmala for women-centred themes and tearjerkers. His mystical pen gave life to Sibichan of Kavalmadam [The Watchtower], the lorry driver Noble, Vidya of Sthreedhanam [Dowry] and Shouri of the recently-published Chaavukadal [Sea of Death], all that bear the hallmark of the writer.

‘If the popular fiction of Malayalam literature has a hero, it has to be Joycy,’ said Sreenath K S, an avid reader of painkili novels and a friend who shaped my own reading in the genre. ‘I started reading his Kanneerattile Thoni [Boat in A Lake of Tears] in the 80s in Manorama weekly, when I was in my teens. I never knew that Joycy, Josey Vagamattom, and C V Nirmala were all the same person, as he had adopted different styles for each. I have felt that Joycy had a poignant style, say, in Ilapozhiyum Shishiram [Winter]. Vagamattom celebrated masculinity in novels like Adiyaravu [Checkmate], while Nirmala could move us by striking the pathos chord in Mizhiyoram [Teary Eyes] and others’. He added, ‘Although I was from Thiruvananthapuram, I could still clearly picture the landscape of Goshree Islands [in Kochi] while reading Thuramukham [The Port], a survival thriller by Vagamattom. The heroes Savio and Harshan, in order to save their lives, travel through the Kadamakkudy Islands and Vyppin. When I visited these places, I was fascinated by the detailing in that novel’.

Chapter 3: Detectives and Sorcerers

The ‘Ma’ publications soon began to search for variety beyond romantic tales as novels that piqued curiosity and the increased circulation became increasingly important. In the 1960s, most Malayalam detective novels used to draw inspiration from English novels by authors like Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Detector, a first-of-its-kind magazine published by B K M Chambakkulam Book Depot in the 60s, was dedicated exclusively to detective fiction. Later, the success of Hindi writer Durgaprasad Khatri’s detective novels—translated to Malayalam by Mohan D Kangazha—including Swargapuri [City of Paradise], Velutha Chekuthan [The White Devil] and Chuvanna Kaippathi [The Bloody Handprint] proved there were a lot of takers for the subgenre.

Kottayam Pushpanath entered the scene in the 70s. Under this nom de plume, history teacher Pushpanathan Pillai perfectly blended history with fiction and action, thereby creating a huge fan base for his novels. All the popular weeklies chased him for his novels. His character, Detective Maxim, smoking his characteristic Half Corona cigar, was popular among readers, and they started to call Detective Maxim Kerala’s own Sherlock Holmes. Later, Kottayam Pushpanath himself started featuring in his novels as the lead character, Detective Pushparaj. Youngster Dr. P P George, who used to write under the pen name Pranab, came up with his character Dr. Bleat, which also became hugely popular. Back then, novels with horror and black magic/sorcery themes had the power to captivate readers and keep them hooked. Ettumanoor Shivakumar was one popular writer in that category.

After Pranab, Thomas T Ambatt, Pathalil Thambi, and Battenbose emerged as the leading detective novelists of the 80s. Among them, K M Chacko, who wrote as Battenbose, was the one who caused the shift from detective fiction to crime thrillers as a popular subgenre in the 80s. Battenbose eventually replaced Pushpanath as the king of crime fiction. Right from his first novel, Doctor Zero, to the recent Casino, Battenbose has come up with nearly a hundred titles. His Rakthamillatha Manushyar [Bloodless People], Ranger, Checkpost, Raathriyude Rajakkanmaar [Kings of the Night] and Havva Beach were all super hits. Many leading filmmakers came forward to make a movie based on Ranger with Mohanlal in the lead, but the plan did not materialise.

The style of thrillers became more filmy in the 1990s. Heroes got introductions akin to mass movies today, mostly during a tense situation. Even punchlines were reserved for them. N K Sasidharan, K V Anil, and Mezhuveli Babuji are the prominent names to have established themselves back then. Some of the superhits in the last three decades include Vanyam [The Wild] by N K Sasidharan, Oxygen by K V Anil, and Sravu [Shark] by Mezhuveli Babuji.

‘Writing crime thrillers is not that easy’, said Babuji in our conversation. ‘Before writing Millionaire and Swarnam [Gold], I visited Dubai and the Kolar gold fields, respectively. White Hill was based on a marble quarry near Velankanni, and I stayed at Vedaranyam for two weeks to understand the life inside a quarry. Before writing a crime thriller, we need to finalise the right setting. Detailing is essential to hook the readers’.

Like Joycy, Babuji too has written novels under different names—K Parasuram, Malathy Vasukkutty, Latha Babuji, and B Hilary—while K K Sudhakaran has used the names M Prasadachandran and M Prasad as some weeklies carried two of their novels at a time.

Despite being prolific, both Sudhakaran and Babuji could enjoy a huge readership and longevity, which they attribute to updating themselves with changing lifestyles, technology, and political scenarios.

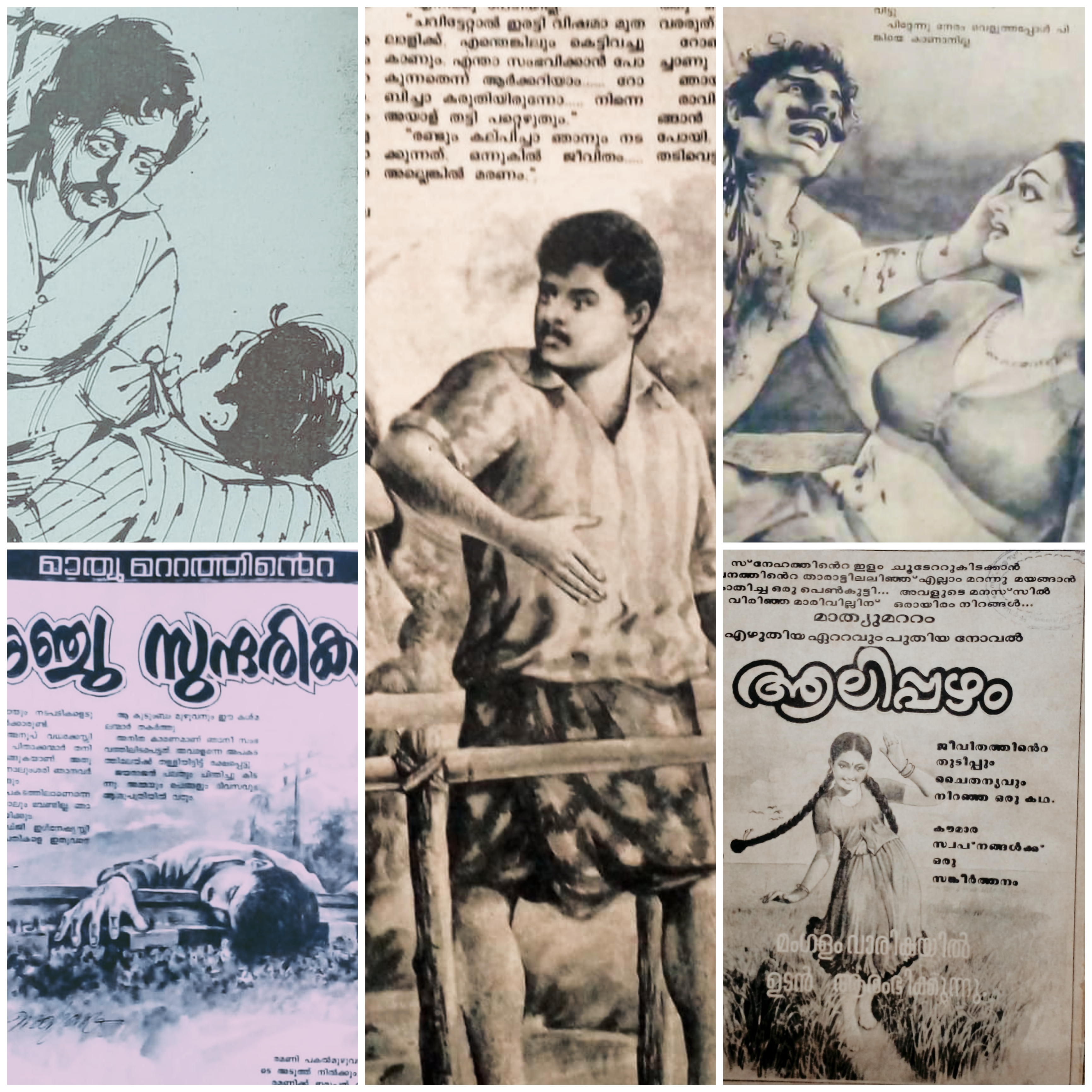

Today, the number of weekly magazines has come down drastically, yet those that survive continue to enjoy good circulation. Nowadays, for a serialised novel that runs into 50-60 parts, the writers get 5,000 rupees per chapter. In the 70s, a copy of the Manorama weekly cost just 70 paise and by the 80s, it rose to 1 rupee. The quality of printing was at average or at times below it, yet the drawings by artists like Mohan—in which beautiful women appeared with voluptuous figures and men with toxic masculinity—kept the readers hooked to the pages. Even the columns were arranged on a page in such a way that one could fold the weekly and read it in total privacy, aboard a bus or in the corner of a tea shop.

Chapter 4: Pulp in Celluloid

Let us get up early to the vineyards; let us see if the vine flourish, whether the tender grape appear, and the pomegranates bud forth: there will I give thee my loves.

– Songs of Solomon 7:12

Whenever a Malayali hears this Biblical verse, the first image that comes to mind will be the love story of protagonists Solomon and Sofia in director Padmarajan’s classic film, Namukku Parkkaan Munthirithoppukal [Vineyards for Us to Dwell In]. The 1986 film, with actors Mohanlal and Shari in lead roles, was based on the short novel, Namukku Gramangalil Chennu Raparakkam [Let Us Spend The Nights in Hamlets] by K K Sudhakaran.

‘Namukku Gramangalil Chennu Raparakkam was published in 13 parts in the Kala Kaumudi weekly in 1985’, said Sudhakaran. Set to be published in a ‘Ma’ magazine, Sudhakaran noted that it was by chance that the editor of Kala Kaumudi, considered a more ‘literary’ magazine like Bhasha Poshini or Mathrubhumi Weekly, read the novel and wished to publish it. ‘Padmarajan’s wife Radhalakshmi read it, and it was she who suggested it to him. I was working at Changanassery at that time. One day, I received a telegram containing Padamarajan’s phone number. He wanted me to meet him at Hotel Samudra in Kovalam’, remembered Sudhakaran.

Padamarajan was writing the script for Nombarathipoovu [Bloom of Grief] back then. Mammootty, Mohanlal, Madhavi, and Baby Sonia were supposed to play the main roles in it. However, after reading Sudhakaran’s story, Padamarajan decided to make a movie based on it before Nombarathipoovu. After discussing the plot with Sudhakaran, Padmarajan decided to use the 21-day call sheet given by Mohanlal for Nombarathipoovu to make Namukku Parkkaan Munthirithoppukal (Samuel, the role set aside for Mohanlal in Nombarathipoovu, was later portrayed by Murali in the 1987 release). ‘It was Padamarajan who suggested to recreate the story with vineyards in the backdrop’, said Sudhakaran. ‘He said the location would give a new colour and freshness to the theme’.

Not just Namukku Parkkaan Munthirithoppukal, but many superhit films from 1960 to 2000 were based on works published under the most successful pulp fiction genre. These include Bharya (The Wife, by Kanam, made into a film in 1962), Neeyethra Dhanya (How Blessed You Are, 1987 film based on K K Sudhakaran’s Oru Njayarazhchayude Ormakku), Kottayam Kunjachan (1990 film based on Muttathu Varkey’s novel Veli), and Kanaka Simhasanam [Golden Throne] by G Usha (2006 film). Actor Jagathy Sreekumar’s 1989 directorial debut, Annakkutty…Kodambakkam Vilikkunnu [Annakkutty…Kodambakkam Is Calling] was based on a comedy novel by J Philipose Thiruvalla, which appeared in Manorama weekly.

Epilogue

The popularity of Ma weeklies started slumping with the advent of mega serials. ‘By the end of 1990s, mega serials started becoming popular and by 2010, the readers, particularly women, switched almost entirely to serials. Some of the most popular pulp fiction novels were made into serials,’ said Sudhakaran.

Babuji opined that Gen-X kids are interested more in mobile phones and they are getting an overdose of content. ‘Movies, movie clips, action sequences, reels, sports, news…it is a plethora of information. They are not very interested in reading a serialised novel as there are plenty of other options’, he said. Weeklies like Manorama and Mangalam were enjoying supremacy till 2010. But now, the circulation has come down, and only Manorama has survived among the ‘Ma’ magazines.

The writers of pulp fiction say such novels are still in high demand from publishers. Publisher T Jayachandran of CICC Books maintains, ‘Publishers can trust pulp fiction writers as these books will be sold easily. Pulp fiction is also the backbone of many libraries in small towns and villages. Joycy, Kottayam Pushpanath, Battenbose, and Muttathu Varkey are still attracting readers to the libraries. Rich is the legacy of Malayalam pulp fiction, and new popular heroes are emerging every year through popular novels.’2

When I asked writer Joycy about the chances of a comeback for lorry driver Noble, one of the most popular characters in Malayalam pulp fiction history, the author was not ready to comment. Such a comeback would be the eighth coming of the hero—Noble has thus far featured in seven titles written by Josey Vagamattom, and given the ongoing popularity of the genre, he has the potential for a re-entry, even in this decade. Pulp fiction admirers will say—we are waiting!

About the Author: Shibu B S is a freelance journalist based in Kochi who has earlier worked with Deccan Herald and The New Indian Express. He is also an associate director to Malayalam film director Unnikrishnan B.

ഷിബു വളരെ നന്നായി എഴുതിയിട്ടുണ്ട് പൈങ്കിളി സാഹിത്യത്തേക്കുറിച്ച്. അതിന്റെ evolution നും നന്നായി ആവിഷ്കരിച്ചു. പ്രേമം, കുറ്റാന്വേഷണം, horror എന്നിങ്ങനെ. ആ കാലഘട്ടത്തിലൂടെ കടന്നും അനുഭവിച്ചും വന്ന ഒരാളെന്ന നിലക്ക് നന്നായി enjoy ചെയ്തു വായിച്ചു ലേഖനം. മനസ്സിന്റെ ഏതോ കോണിൽ മറവിയുടെ മാറാല പിടിച്ചു കിടന്നിരുന്ന ഒരു കാലഘട്ടത്തിന്റെ ഓർമ്മകളെ പൊടിതട്ടി എടുത്തതിന് “അല“ ക്കും ഷിബുവിനും നന്ദി .

രാധാദേവി