Why are the state and the public unwilling to accept the hereditary rights of the protesting fisher community at Vizhinjam? In answer, the protests must be located within broader histories and discussions. Ala presents a translation of Sindhu and Robin’s article on the Vizhinjam protests first published in our September 2022 issue.

Read the original in Malayalam here.

Sindhu Nepolean, Robin Titus

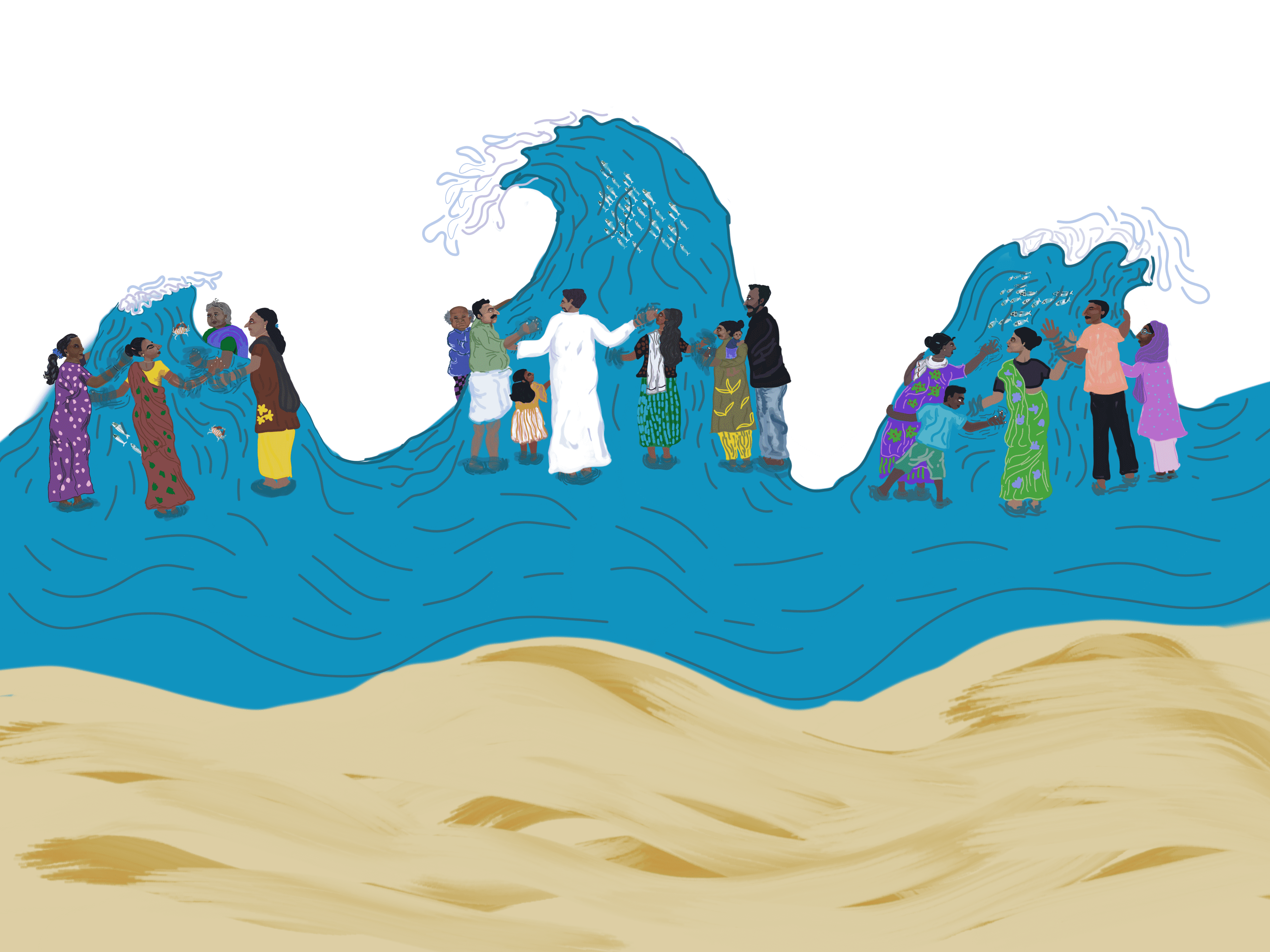

We are living in times where the intergenerational and inalienable rights over land and sea of Kerala’s coastal communities have been thrown into unprecedented crisis. In the 80s, marine workers’ political movements for better employment and education comprised a major voice in the paradigm-shifting popular challenges to state power in Kerala. Today, the same communities are protesting for sovereignty over their lands and resources. They have been brought to the battle lines by factors including corporate capital-driven coastal development projects, the commercialization and monopolization of fisheries, climate change, and the governments’ negligence of their issues.

Though Malayalis are used to the slogan, ‘the forests belong to the forests’ children’, they may be less familiar with ‘the seas belong to the children of the sea’. This may be why they are yet to see the ongoing protests by fishing communities demanding an end to coastal erosion as a movement for human rights. These popular protests emphasize the need for Thiruvananthapuram’s artisanal fishers’ sovereign and unconstrained rights over the ‘coastal commons ‘—coastal land, sea, and associated resources—that they exclusively rely on for their livelihoods and sustenance.

For several years now, the fishing families that lost their homes in the coastal erosion and flooding owing to the construction of an international trans-shipment port at Vizhinjam, Thiruvananthapuram district, have been living as refugees in concrete warehouses. In the past few years, very many houses have been reduced to rubble as massive waves broke upon the coastal villages near Thiruvananthapuram’s urban center, in the district’s northern regions, and in southern coastal villages like Pozhiyoor. It is in this context that coastal communities have begun fasting in protest, demanding that port construction activities be halted until a durable solution for coastal erosion is arrived at.

The protest, which began on the day after Independence Day in 2022, is being led by the Latin Catholic clergy. For long, public discourse in Kerala has attempted to portray Latin Catholic marine workers as people without political agency who are puppets of the Latin Catholic church. This time too, the state continues to reduce the protests to a conspiracy by the church. Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan’s statements implying that it is not the local communities alone that are leading the protests, and that protests in some places have been pre-planned, all feed into this dominant stereotype of the community. In recent times, the state’s preferred means of crushing popular dissent has been to try and establish the presence of Maoists and terrorists in such movements. These acts of state power are likely driven by the mistaken faith that such protests can be quashed or that public opinion can be turned against them. In the case of the Vizhinjam protests, the Chief Minister, representing the interests of the Communist government, hastens to establish such ‘outside influences ‘ by alluding to the presence of white-clad priests.

At the same time, the port protection committee set up by local BJP workers has deemed that the protests are led by Christian terrorists. In short, the parties leading both the state and national governments deploy the same logic to condemn a group of people protesting against a corporate owned by the second richest man in the world. The state thereby becomes a major part of public discourse vilifying coastal communities. The army exercises conducted in coastal regions during the pandemic and the violence wrought upon women fishers at the time must all be seen in this light.

Researchers who work with coastal communities have also countered the problematic ways in which popular understandings of fishing communities are shaped. Kalpana Ram (1991), studying the fishing communities in Kanyakumari, has noted that fishing communities’ differences from dominant Hindu agricultural communities have, while leading to marginalization, also shaped a strong sense of identity among coastal communities. While non-dominant caste communities in the hinterlands were bound up in hierarchical relations of agricultural production with dominant-caste groups, such master-slave relations did not characterize coastal regions. Consequently, coastal populations have historically developed an identity irreducible to caste relations (Ram 1991).

Similarly, Ajantha Subramanian’s study of fishing communities in Kanyakumari also strongly counters the argument that coastal communities lack political agency. Subramanian (2009) clearly lays out how the community has a long history of pushing back against the state and the church through their own political interventions. However, she makes it clear that coastal communities and their politics do not exist outside such relations of power. Rather, they have themselves deployed the language and symbols of authority in their politics (ibid).

Both Ram’s and Subramanian’s arguments are crucial with respect to the Vizhinjam protests led by Latin Catholic fisherpeople.

Revisiting the history of postcolonial Kerala, one can discern some of the milestone political interventions carried out by fisherpeople. An example is the movement by artisanal fisherpeople to protect their livelihood and environment against the mechanized fishing industry. Latin Catholic fisher communities have been able to lead powerful movements and assert their rights without the patronage of political parties. When times changed, as a passive response to the capitalist transformation of the fishing sector, these communities have also adapted by themselves adopting new methods of fishing. In recent decades, as fishing livelihoods became threatened by the factors mentioned at the beginning, artisanal fisher people and their children have adapted yet again by migrating first to the Middle East, and then to Europe. Latin Catholic fishing communities have thus proved that, much like any other community, they too can leverage their own communal resources and relationships to survive in the face of challenges by corporate capital and state power. This is evinced by the ways in which these communities have progressed as a result of migration to foreign countries. At the same time, these communities also continue to intervene politically to ensure their hereditary livelihoods, as the Vizhinjam protests amply demonstrate.

Apart from a willingness to adapt, Latin Catholic fishing communities remain invested in protecting their cultural worlds. Currently, most young people in fishing communities refuse to take up hereditary fishing work as their primary occupation. Most prefer to migrate abroad or seek other means of employment at a time when fishing fails to support even a basic quality of life or education. At the same time, this new generation has made its presence felt in protest spaces, recognizing and asserting their generational rights over coastal land and sea. As long as families rely on fishing for livelihood, the question of rights to coastal commons remains relevant.

Let us suppose that coastal erosion continues unabated and that all the fishing families leave their coastal localities behind, or that they would be relocated through state schemes like Punargeham 1, forcibly or otherwise. Who would then take up custodianship of the coastal commons? It accrue to the same state and civil society that saw as an illegal act of encroachment of public land the recent attempt by fishing communities in Adimalatthara village to build housing on their shores with the involvement of the Latin Catholic church. And so, one wonders what the real issue of the state is—the apparently irrational insistence of fishing communities on living in unsafe regions, or the unwillingness to recognize that the coastal commons are, first and foremost, the sovereign space of fishing communities.

To be sure, the state’s disapproval of church leadership is understandable—the constant intervention of institutionalized religion in state-citizen relations is a matter of concern in any democracy. The political milieu in India today shows us the extent to which the everyday influence of religion and its institutions can corrode democratic setups. Hence, problematising the role of the Latin Catholic church in the Vizhinjam protests is a necessary move for anyone who believes in democracy. However, it is farcical to think that such a move entails seeing fishing communities as lacking political agency and as entirely under the thrall of the church.

Rather, the Latin Catholic and fishing communities have constantly negotiated with one another, engaging in conflict and dialogue throughout history. In fishing villages, believers are able to convey their opinions to the clergy and even oust religious leaders who do not respect their opinions. Indeed, Ajantha Subramanian’s Shorelines (2009) begins by describing a community of Latin Catholic fishers who took to court the bishop that enforced a ban on fishing in their village. In short, the relationship between the Latin Catholic church and its followers in fishing villages is not a top-down one. On the contrary, it is a relationship characterized by complex mutuality that the state and civil society cast in simplistic terms.

The current government is one that has massively failed its coastal communities—by failing to provide adequate warning about the Ockhi hurricane, by falling grievously short in post-disaster rescue operations, by being unable even to arrive at an accurate count of those who were affected, by succeeding only in frequently reminding the public of the size of the compensation packages it gave to the families of those who died. It is a government that also rendered invisible fishers’ movements for their rights by dubbing them ‘Kerala’s army’. The state’s violence also played out at the height of the pandemic—through a massive deployment of the army, unseen anywhere else in India at the time, to instill fear into a fishing village and its people, and through restrictions imposed on women fishers in the name of COVID-19 prevention and law-keeping. The state, of course, is simply manifesting a more extreme form of the racist attitudes that civil society has always maintained towards fishing communities.

The Vizhinjam protests, therefore, must be located within these broader histories. It is the need of the hour for the Vizhinjam protests to evolve into a broader popular resistance without succumbing to the fate of so many other movements for rights. The Vizhinjam protests remind us that ongoing discussions about special human rights at the international level must also be able to bring about changes in local contexts.

References

- Ram, Kalpana. 1991. Mukkuvar Women: Gender, Hegemony and Capitalist Transformation in a South Indian Fishing Community. Zed Books.

- Subramanian, Ajantha. 2009. Shorelines: Space and Rights in South India. Stanford University Press.

About the Authors: Sindhu Nepolean is an independent journalist who is a Research Assistant at Sussex University. Robin Titus is a PhD student in Sociology at IIT Bombay.

Photo credits: Robin Titus

Translated by: Shilpa Parthan

Nice post author. Thank you. Keep it up.