Focussing on two Malayalam films from the last decade—22 Female Kottayam (2012) and Varathan (2018)—Arun Ramesh argues that despite their apparently progressive politics, new-generation films continue to be influenced by feudal norms and practices.

Arun Remesh

The Beginnings of New-Generation Malayalam Cinema

As a 90s kid, what excited me was the masculine characters in cinema who challenge the police, defeat the villain, and save the heroine. We used to applaud and admire Jagganathan (Aaraam Thampuran, Shaji Kailas, 1997), Narasimha Mannadiar (Dhruvam, Joshiy, 1993) and Bharathchandran IPS (Commissioner, Shaji Kailas, 1994). The macho heroes in these films were the role models for most young kids who used to imitate them in action and dialogue delivery. These movies projected the hero as the supreme authority who delivers justice. Jagganathan has returned from Bombay to conduct a temple festival in his village, thus liberating it from the clutches of the villainous Kulappulli Appan. Mannadiyar is a king-like character, a protector who helps everyone and is applauded for ‘giving a life to’ (marrying) a poor woman when her father was unable to pay off his debt. Bharathchandran was an upstanding police officer who raised his voice against corrupt politicians and the police. We learned by rote the ‘bombastic’ English dialogues he used, throwing them around during fights with our classmates, though the meanings of these dialogues remained unknown until we learned English.

These characters and their peculiarities remain with us even after two decades because they were played by our favourite actors. We used to call these films Mammootty films, Mohanlal films, or Suresh Gopi films—the directors’ names were hardly in the picture for a kid mesmerised by the aura of the characters. We rarely find these actors struggling to find a livelihood but struggling to preserve their family, wealth and their family status.

Today, these characters have largely disappeared from cinema, and live on only in the nostalgia of a 90s kid. With the internet explosion and the availability of foreign films and films in other Indian languages, most of them dubbed in Malayalam, our ideas of the city and a hero have attained various other dimensions. A few 90s films have seen sequels released, showing the life of the previous hero’s son who exactly looks like his father or of the same character taken from the 90s straight to the present world. A prominent example is the CBI series crafted by K. Madhu and S. N. Swamy, which, in the 90s, introduced a different trajectory to the crime thriller genre in Malayalam cinema. The latest instalment, CBI 5: The Brain (2022), features the same protagonist—the brilliant investigator, Sethuram Iyer. The film has been criticised by cinephiles for presenting the film as if Sethuram Iyer has simply travelled in time from 2005, when the fourth film in the series was released.

Over time, Malayali film enthusiasts have moved on from simply watching the films and accepting the characters to demanding logical as well as reasonable answers to their questions. The internet boom equipped them with the knowledge of various other films in different genres and new techniques in cinema. Though we had film magazines and film festivals in Malayalam since the 1960s, the internet opened up for us the world of Korean films, which rarely featured in popular discussions, except for a few films screened at film festivals.

Films from earlier decades are beginning to be reexamined and criticised for their treatment of the marginalised and their comments on individuals with disabilities. These movies focused on individuals who were portrayed as messiahs coming from an outer world to bring order to the state of things. They had an intention, a duty to be done, which would mainly comprise a revenge plot wrapped in colourful songs, humour, and romantic scenes. Malayalam film director Lenin Rajendran blames the aura of the superstars for the stupor into which the Malayalam film industry had fallen (Jayakumar and Ranjith 2008). In those days, says Rajendran, fan clubs demanded that films project and buttress the image of the particular actor rather than the actor becoming a catalyst in the representation of the character. This influenced the industry as a whole as fan clubs greatly contributed to the production and circulation of films. This prevented the emergence of new patterns, new directors, different modes of narration, and experimental films. Dubbed films from Tamil and Telugu set up a new terrain from 2004 onwards, drawing audiences to theatres at a time when Malayalam films failed to make a profit.

One of the earlier attempts to imitate the style of dubbed films can be seen in the films of the Malayalam director Jayaraj. His film 4 The People was released in 2004. As the name suggests, the film was for the people—with its structure, theme, and actors. The actors were unfamiliar faces, and they were chosen based on the requirements of the characters, unlike the existing style of writing a character based on the requirements and possibilities of the actor. In one of his interviews, Jayaraj attributed the success of the film to this experiment with new actors, using a language different from the popularly-used Malayalam language,1 and bringing the movie closer to life. The song ‘Lajjavathiye…’ was characterised by popular images of ‘traditional culture’ in Kerala—Kathakali, a traditional art form within the confinements of caste and class usually performed in private spaces and within the temple premises, and Mohiniyattam, a similarly confined art form. What makes this song striking is the juxtaposition of these so-called traditional attires and the attire of the hero and the heroine in modern clothes. This combination is presented in the same frame, but the placing of these modern individuals in the foreground and the traditional art forms in the background suggest the existence of both and the need to focus on the modern. The song, sung by the singer Jassie Gift, unique for his name and voice, was a superhit among youth at the time. In general, the film was noted for its novel representation of contemporary society and the response of four individuals to social injustice.

This was a new beginning, inspiring many other directors from the mainstream and encouraging new directors to make films with new actors, thus reducing production costs and liberating themselves from the aura of the superhero. Though this is the case, I argue that some of these films remain rooted in feudal ideologies, hidden beneath the surface. These films appear new in their structures and representation of a different type of hero and heroine from the films of the previous era, but they continue to foreground gendered as well as feudal norms in a subtle manner, as I explore below by analysing two films that have been celebrated for their representation of depicting characters different from the way they were represented.

22 Female Kottayam (Aashiq Abu, 2012) and Varathan (Amal Neerad, 2018) belong to the second category of the Malayalam new generation cinema. By the second decade of the 21st century, new-generation cinema became more visible and popular by marginalising the stardom of the previous generation. We will be looking at the elements that make these films ‘new’, apart from the plot and representation of characters, focusing especially on the values they try to communicate with the audience.

***

New Decade, New Possibilities: The Capable Woman

22 Female Kottayam, released in 2012, has been appreciated for its different style of representation of women. The protagonist, Tessa, is a nursing student studying in Bangalore. Coming from a village in the agrarian Kottayam district, Tessa aspires to move to Canada for career opportunities. She befriends Cyril, who works at a travel agency. They begin a relationship, but it is ruined when Cyril’s superior, Hegde, rapes Tessa. Though Cyril supports Tessa, she later finds out that it was all planned with the support of Cyril. She reacts to him cheating on her but is trapped in a drug-trafficking case and sent to prison. She gained the respect and acceptance of her fellow prison mates when she helped one of them deliver a baby. Here, she gains confidence in her abilities and decides to take revenge with the help of her prison mates. In revenge, she kills Hegde using a snake, and under the pretence of reconciliation, sedates Cyril after intercourse and performs a penectomy on him.

In the film, it is Tessa’s professional knowledge that enables her to return to pursuing her ambitions and take revenge. The film portrays Tessa as a brave young woman, unlike earlier portrayals of women protagonists whose only role was to be protected. Tessa is helped by her female prison mate in her revenge. The film also normalises frequently devalued dialects of Malayalam by showing Tessa as speaking in a Kottayam dialect. When Cyril tries to correct Tessa for her pronunciation, she asks him what’s wrong with it, challenging his act of trying to ‘improve’ her.

Tessa often has to offer her body to get things done, in instances that serve as a critique of patriarchy. For example, one of the many who help Tessa get her revenge is DK, a man who extends help with the expectation of a relationship with Tessa. It is the illegal contacts and aid she finds from the prison that enable her to find Cyril and Hegde; the legal system does not come to her assistance in this case. By penectomising Cyril, Tessa proves her capabilities as a woman who becomes a threat to society by challenging the patriarchal system. The film ends with Tessa leaving Kerala, which can be read as her achieving her dream of going abroad. But this act of leaving the space can also be read as an exile from society by a capable woman who does not have a place in patriarchy. Nevertheless, unlike the prevalent pattern in which a man takes revenge, usually on behalf of his mother, wife, or sister, Tessa represents an educated, capable woman who knows her potential. If Tessa’s is a story of escaping from a space of patriarchy, Abin and Priya’s journey in Varathan (The Outsider) is one of zooming in on the feudal nature of village relations, as we shall now see.

The Feudal Justice in the Non-Feudal Forms

We have come across the hero who has returned from the city, standing up for the village and its traditions and values. The city transforms the innocent ‘tharavadi’ 2 individual into a gangster. The circumstances in the village make someone poor, jobless and even a thief. On the other hand, the city offers him shelter, a job, and an opportunity to display his abilities/efficiency and prove his honesty. The city in these films represents a place of corruption and power. It is the dedication of an individual to his work which earns fortune for the hero. Aaramthamupran and Aryan are some of the films with these plot tropes.

New-generation Malayalam films, however, have a different pattern. The city is presented as a dynamic, accommodative and inclusive space rather than a stable place, one in which individuals interact and leave behind their traditional badges. The village in the old-generation films was glorified for their innocence. But this romanticised view of the village changes in the new generation films. Varathan (The Outsider), directed by Amal Neerad and released in 2018, tells the story of Abin and Priya returning from the Middle East to spend some time in Priya’s father’s estate in a hill station in Kerala to recover from the loss of their baby. Abin had recently lost his job. They decide to spend time in the estate, which is a different space. The villagers are a bit sceptical of Priya’s attire and how Abin behaves toward her. Unlike the traditional household, where separate spaces are allotted for men and women, denoted as domestic and public, Priya and Abin share their spaces. We find Abin making tea for Priya while making tea for their manager. The husband making tea for his wife and serving tea is a strange idea to the manager. The neighbours, who were the tenants of Priya’s father’s property have now become more powerful, and their younger generation intrudes into the life of Priya and Abin. Abin uses his knowledge of science and the available materials, using his abilities as a bricoleur to defend his family from intruders.

Fahadh Faasil and Friends; Amal Neerad Productions.

The film discusses the life of modern individuals by placing them within the structures of the village, which primarily consists of individuals who are still in their primitive value systems, very much bothered about social boundaries and watching everyone as an intruder with a suspicious eye, creating a sharp contrast between life in the city and in the village. Varathan, as the title reads, creates a lack of knowledge about the outsider—in this case, Abin. One of the characters asks what Abin is doing in Dubai. We are not told more about Abin’s past or his parents. Abin’s mysterious nature remains unfolded in the movie. His transformation from a silent individual to someone furious and capable is drastic and it even surprises his wife. On the other hand, Priya is a modern individual who knows her freedom and values her personal space, she reacts when she finds someone entering their personal space. Abin, on the other hand, rejects Priya’s arguments and tries to calm her by saying that it would be her thoughts. Though there are various instances in which Abin realises that the villagers are not as innocent as he thinks and gaze at him suspiciously, he is not willing to believe Priya. On many occasions, Priya tells Abin that the people are not innocent as he thinks. Abin carelessly neglects Priya’s worries and reacts only when she is harassed. Abin’s rage is fuelled by the arrival of Preman, who brings milk to the house, and his mother, seeking shelter from the feudal family that tries to hurt Preman for talking to their daughter. It is a realisation that he is not only in charge of his family, but also in a responsible position to help whoever seeks help from him. The caste-class hierarchies of the village are visible in their dialogues, appearance, and helpless situation. Abin’s sudden transformation into a ‘responsible’ individual is a combination of modern values and feudal values. Abin fails to protect his wife. The helplessness and his realisation of the intrusion of the neighbours into his family anger him. It is quite interesting to look at the spaces where the major events happen. Priya is attacked while he was outside the territory of their property, and was alone. The transformation of Abin happens within the territory of his property. The private property is shown as a safe place and its safety has to be preserved when someone tries to intrude into the private space.

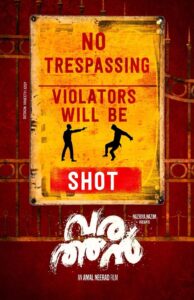

While Priya is helpless, and in many instances, her space is restricted within the compound of their property, Abin becomes a protective feudal lord when he decides to save Preman and his mother, who come to him for help. He refuses to leave the house, instead waiting for the local feudal family to come to his property. The police or other agents of modern law are absent in the film. One of the brothers who come to Priya’s house in search of the hiding son and mother is a police officer. Here, the police officer acts as part of the feudal order, not as part of the state. Instead of being a servant of the state whose responsibility is to protect the individuals, he functions as an agent of the feudal structure. It is this particular identity of the police officer as an extension of the feudal structure that is challenged by the hero. Abin represents the good and responsible agent of the feudal structure (a trope in the old generation cinema) who demands the help of the state and delivers feudal justice. As film critic Madhava Prasad points out, the police arrive late to witness the feudal justice rendered in the absence of the police by the hero (Prasad 1998: 95). By creating a suspicious identity for Abin, even to the surprise of his partner Priya, the film casts a more nuanced lens on the feudal heroes trained by the city. Abin’s transformation is two-fold, that of a modern individual defending his property and private space from intruders, and that of an individual who takes up the mantle of a feudal lord by becoming a saviour, a responsible individual who guards the life of his fellow beings. Though Abin is disturbed and feels guilty for not protecting his wife from the troublemakers, he decides to help Preman and his mother who seek refuge in his house. He uses these refugees as bait to trap the intruders within his territory. While Priya is abused when she was outside of their property, the boundary and the idea of one’s property offer a lot more confidence and a sense of protecting the individuals to Abin. If his family was attacked within their compound the situation would have been different. The space—the house—has a lot of significance in enabling Abin to take revenge. Priya leaving the compound without the presence of her husband is presented as a threat. Similarly, the absence of a father figure leaves Preman and his mother helpless in the situation. Varathan rejects the romanticised picture of the village which is so innocent and accommodating and replaces this image with a bunch of people who exploit others. Though Priya is returning to her father’s plantation in the village, she remains an outsider to all except her school teachers. The film represents the claiming of one’s ancestry and traditions. Here it is Abin taking charge of his father-in-law’s property. It is not Priya who claims it but Abin, the husband who discovers the gadgets of his father-in-law and decides to attack the intruders. Abin is taking revenge, not Priya, the victim; the feudal structure focuses on the male character for taking revenge, not the female character. The film concludes by suggesting that feudal authority can be challenged only by possessing feudal values and defensive mechanisms. Abin does it successfully and the sense of claiming and expressing his authority is revealed in the climax scene in which he hangs the board: “No trespassing. ‘Violators will be shot’”.

***

Though the new generation of Malayalam films is structurally better than their counterparts in the previous generation, notably for the inclusion and representation of the marginalised and women, the patriarchal ideologies do creep into these structures in disguise. Women as vulnerable and have to be protected remain unchanged. It is the male hero who comes to save the family and takes revenge. If a female character tries to imitate the male-heroic stand of vengeance and delivering feudal justice in the absence of the law, she is presented as a threat to the system and does not encourage her presence in our society. Interestingly in the films we analysed, the state does not interfere in delivering justice to the victims—as Prasad (1998) points out, the absence of the intervention of the state is filled by the feudal hero. Here the hero does not belong to the feudal structures—the family or the tharavad which used to help the poor seeking help—but is a modern individual who has some relations with the city. The realisation of the feudal connections and responsibilities enables the hero to render justice. While Abin decides to assert his power as the owner of the plantation, Tessa needs to leave Kerala society. The Malayali consciousness does not approve of her existence in society as she does not belong to the notion of women who need to be protected. Though these films appear to be new in their treatment of women, they are suggesting that they are still vulnerable and needed to be protected by men, thus taking one back to the feudal notions of protection and gender roles.

References

- Jayakumar, K P, and Ranjith K R. 2008. ‘Oru Peedita Vyavasaayam’ [An Industry Under Duress]. Samakaalika Malayalam Vaarika, 12, no. 30:109–114.

- Prasad, M. Madhava. 1998. Ideology of the Hindi Film: A Historical Construction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

About the author: Arun Remesh is a PhD Research Scholar at the Department of Cultural Studies, English and Foreign Languages University, Hyderabad.

Editor’s Note: This article is one of six articles written by participants from our 2022 Writing Workshop, and part of Ala’s fourth-anniversary specials: Issue 49 and Issue 50.