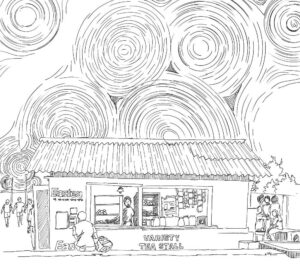

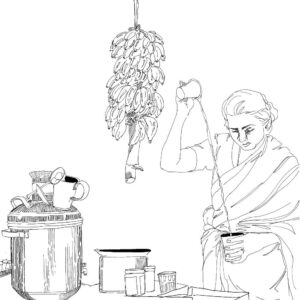

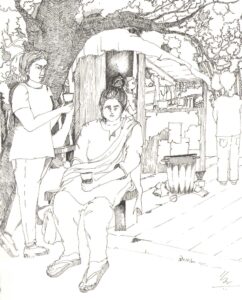

Accompanied by her original sketches, Gaya Hadiya shares experiences of chayakkadas in Kerala, highlighting how they reflect gender, caste and class relations in the region.

Gaya Hadiya

It is curious how many cultures around the globe have established systems of living that keep their young women indoors.

A few years ago, on a trip with friends to the small, isolated mountain village of Rasol in the Parvathi Valley, we noticed something rather strange by the end of the first day. There were no young women to be seen on the streets. There are toddlers running all around, so there have to be a few young women in this village, I thought to myself. As it turned out, it was rubbing season and the young women sat at home rubbing Cannabis leaves, making hash out of it, while the older women and men went to the farm or to the market. Soon enough, we came across the young women on our walks along narrow lanes, sitting in front of the houses in groups or by themselves, at work.

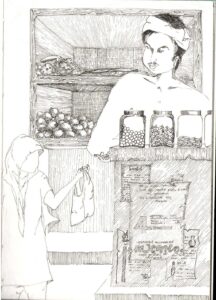

Whereas this social setup and spatial segregation seemed strange to me then in a different and remote culture, I have a fair working knowledge and lived experience of such spaces in Kerala, where I was born and raised–spaces which were denied and continue to be relentlessly fought for. The chayakkada (tea shops) would be the first and foremost on my list. Chayakkadas hold a significant place in the cultural demography of Kerala. The history of tea shops cannot be separated from the history of anti-caste movements in Kerala. Sharing a meal is an intimate act that, for centuries, was considered appropriate only within the caste groups. Tea shops were an act of revolution as they created a secular food-space unheard of till the 19th century. People in Kerala, till then, ate together within the family or within the ritualistic frameworks of religious institutions. This isn’t surprising, considering the extent to which we practised untouchability as a society.

Whereas this social setup and spatial segregation seemed strange to me then in a different and remote culture, I have a fair working knowledge and lived experience of such spaces in Kerala, where I was born and raised–spaces which were denied and continue to be relentlessly fought for. The chayakkada (tea shops) would be the first and foremost on my list. Chayakkadas hold a significant place in the cultural demography of Kerala. The history of tea shops cannot be separated from the history of anti-caste movements in Kerala. Sharing a meal is an intimate act that, for centuries, was considered appropriate only within the caste groups. Tea shops were an act of revolution as they created a secular food-space unheard of till the 19th century. People in Kerala, till then, ate together within the family or within the ritualistic frameworks of religious institutions. This isn’t surprising, considering the extent to which we practised untouchability as a society.

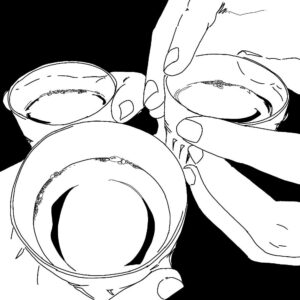

Tea shops allowed the people of Kerala to share a space as individuals and allowed conversations across persuasions and sensibilities. This led to a synthesis of ideas as well as lifestyles. Getting past some of the outdated practices became inevitable after this. The role that these neo-secular food-spaces played in blotting out an existing power hierarchy, hence, is commendable. Nevertheless, this was done by keeping another hierarchy intact–that of gender. The individual who was acknowledged and celebrated in these spaces was male. Irrespective of the class, caste, and creed, most of the public spaces stayed inaccessible to women. The chayakkada was no exception.

Tea shops allowed the people of Kerala to share a space as individuals and allowed conversations across persuasions and sensibilities. This led to a synthesis of ideas as well as lifestyles. Getting past some of the outdated practices became inevitable after this. The role that these neo-secular food-spaces played in blotting out an existing power hierarchy, hence, is commendable. Nevertheless, this was done by keeping another hierarchy intact–that of gender. The individual who was acknowledged and celebrated in these spaces was male. Irrespective of the class, caste, and creed, most of the public spaces stayed inaccessible to women. The chayakkada was no exception.

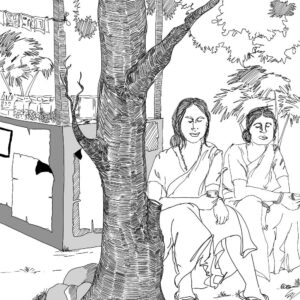

The mere sight of a tea shop was intimidating for my teenage self. It was beyond unusual to see women of any age hanging out at a tea shop in Kerala. Shilpa Padhke talks about the need for women to look purposeful while occupying public spaces in her book, Why Loiter. Loitering is not a luxury women have in our country. They will be interfered with and interrogated in order to remind them of this rule if they are found to be behaving not in accordance with it; more so in the case of young women.

This is why the accepted rule in Kerala is that a woman has no business being in a tea shop. All the ‘respectable’ things women are allowed do not include socializing in the local tea shop. At least, not where I grew up. Even within the presumably more respectable space of my school, female students always bought what they needed at a window at our canteen rather than sitting at the tables. This was highly inconvenient for everyone involved, but still a custom to be followed. In my teenage years, some friends and I would skip class to go sit in the school canteen to finish assignments that were due. This offended the entire school. I remember the most offensive and unacceptable part of this entire ‘misconduct’ was that three sixteen-year-old young women chose to go sit in the canteen! We were told that it was inappropriate for young women to do so.

This is why the accepted rule in Kerala is that a woman has no business being in a tea shop. All the ‘respectable’ things women are allowed do not include socializing in the local tea shop. At least, not where I grew up. Even within the presumably more respectable space of my school, female students always bought what they needed at a window at our canteen rather than sitting at the tables. This was highly inconvenient for everyone involved, but still a custom to be followed. In my teenage years, some friends and I would skip class to go sit in the school canteen to finish assignments that were due. This offended the entire school. I remember the most offensive and unacceptable part of this entire ‘misconduct’ was that three sixteen-year-old young women chose to go sit in the canteen! We were told that it was inappropriate for young women to do so.

The degree of misconduct associated with women occupying public spaces changes with elements such as class, caste, age, marital status, and whether or not they are accompanied by a guardian figure. For example, the sight of a young girl running an errand is not a rare one, even though in most cases she is accompanied by a male sibling. Similar is the case with elderly women.

The degree of misconduct associated with women occupying public spaces changes with elements such as class, caste, age, marital status, and whether or not they are accompanied by a guardian figure. For example, the sight of a young girl running an errand is not a rare one, even though in most cases she is accompanied by a male sibling. Similar is the case with elderly women.

Interestingly, the very ‘inclusive’ nature of these spaces was (and remains) a reason why women are not expected to access these spaces freely. A common excuse for denying women access to these spaces is that ‘all kinds of people’ come there, and hence it is not an appropriate place for young women. Beyond the obvious and often discussed issue of women being considered the property of men, a logical conclusion one can make out of this situation is about the casteism underlying this injunction. This injunction starts from the idea of a woman as something that is owned by a man–a father or a husband–a property he believes belongs inside of his household. He does not agree for it to be out there in the world. This property of his is not safe in a public space ‘where all sorts of men’ come, he believes. He arguably fears that it could be stolen; that someone else could claim ownership of this property of his.

Despite these restrictions, there are certain groups of women who have regular access to these tea shops. It is not uncommon for women who go for daily wage work, women who work for the thozhilurappu padhathi (Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme) to be taking tea breaks in one of these shops. Do they have the same kind of access to these spaces as men? No. Nevertheless, they get to walk into one of these ‘inclusive spaces’ and be a part of the landscape. It is an understood thing that the women who are seen in these spaces belong to the underprivileged strata of society. To be seen in such spaces, therefore, is seen as involving the ‘risk’ of being mistaken for someone who belongs to these lower strata of society. It is safe to conclude that these so-called inclusive spaces continue to maintain caste, class, and gender hierarchies—they remain just another safe space for dominant-caste cis men to practice their privileges.

This implicit ban on young women in public spaces is closely related to the question of their safety in public sensibilities. At least, it is presented to us wrapped in the promise of safety; in other words, a threat of attack and assault. By telling us that we will be safe if we behave in such and such fashion, we are being told that our safety is a reward for appropriate conduct. This is another aspect Shilpa Padhke closely analyses in her work–the parallels drawn between respectability and safety for a woman.

Let us take a moment to consider the contexts in which these behaviours are deemed appropriate. Something becomes inappropriate when the action challenges or jeopardizes the internal coherence or continuity of a situation; when the action is in conflict with the rules of the game. Since women are being told what is and is not appropriate behaviour, it is safe to assume that the rules of the game have already been set. Any action coming from a woman that is not in accordance with the set rules can be understood as an attempt to amend these rules. Women are expected to be mere players of the game set by society and it is unacceptable when they take the position of a decision-maker.

Let us take a moment to consider the contexts in which these behaviours are deemed appropriate. Something becomes inappropriate when the action challenges or jeopardizes the internal coherence or continuity of a situation; when the action is in conflict with the rules of the game. Since women are being told what is and is not appropriate behaviour, it is safe to assume that the rules of the game have already been set. Any action coming from a woman that is not in accordance with the set rules can be understood as an attempt to amend these rules. Women are expected to be mere players of the game set by society and it is unacceptable when they take the position of a decision-maker.

It is only by claiming such denied spaces, by constantly playing the decision-maker role, that a change can be brought about. It is heartwarming and reassuring to see women today putting in that extra effort to unlearn the set rules, reimagine public spaces, and be the difference they wish to see. It is not as unusual to see a couple of women hanging out at a tea shop in Kerala anymore.

About the author: Gaya Hadiya is a Philosophy graduate, currently working as a project associate at IIT Dharwad. Epistemology, ethical concerns about AI, women and urban spaces and contemporary art practices

are some of her areas of interest. For the past couple of years, she has been working on

understanding urban spaces and the relationship women establish with those spaces through

her sketches. You can find more of her works here.

Beautiful narration… great to read about teashops…there are some famous and nostalgic tea shops…carrying lot of legacy…and during trips people use to stop and step down at these specific ones…”chaya” and “kadi” both have specialities in such shops…and the taste varies from Kanyakumari to Kasaragod. Congratulations and best wishes

Good writting.