Working closely with Kerala’s fishers, the Forecasting with Fishers team developed the localised weather forecasts that they need to survive. But how can artisanal fishers use this technology when they are often under-resourced or far at sea? Members of the ‘Forecasting with Fishers’ project team write about the process through which they developed tools for fishers in Kerala to effectively access and understand weather forecasts.

This article is part of Ala’s special issue on the Forecasting with Fishers project. Check out their website for more articles, interviews, and features about the project.

Kate Howland, O. B. Roopesh, and Max Martin

“Most young fishermen are using Windy. We also get warnings from the local church. Still, these messages are not very clear. They won’t say whether an event will actually happen. In such a situation of uncertainty we look at Windy and go to work. We just enter our location in Windy and then figure out the wind speed over there.” (Puthiyathura fisher)

To secure their livelihood, fishers need to be able to balance caution with opportunity when it comes to assessing weather-based risks. Access to accurate and precise weather forecast information can even save their lives.

Background

In the Forecasting with Fishers project, we examined how Information and Communication Technology (ICT) tools can be used to support the dissemination and uptake of weather forecasts among artisanal fishers on the Kerala coast. Our previous research in two villages in the Thiruvananthapuram district (Anchuthengu and Poonthura) in 2018 had indicated that weather forecasts and alerts can be too generic and expressed in a way that does not give fishers the information they need to make decisions. Marine forecasts are usually issued in English and often use technical terms unfamiliar to fishers. Additionally, warnings of severe weather can take the form of blanket fishing bans that last many days, and turn out to be locally irrelevant, meaning that to always follow them would be a risk to livelihood. We identified the need for regular bulletins in Malayalam and the potential benefits of graphical visualisation of crucial weather information based on location-specific weather models. Our observations and conversations, as well as our analysis of boat-logs1 suggested that forecasts need to be area-specific, timely, precise, reliable and accurate, and geared to seasonal fishing practices and daily routines. We also identified the need for more opportunities for forecasters and fishers to share notes on their knowledge, concerns and challenges, thereby enabling informed decision-making in fishing. From this work, we had anecdotal evidence that smartphones are increasingly being used to access weather information online and have the potential to support the need for more precise forecasts.

Understanding Fishers’ Existing Practices

To explore this further, we began by looking into how fishers were currently accessing weather information through existing ICT tools, and the extent to which they found forecasts useful. Our early interviews in three other villages in the district (Marianad, Vizhinjam, and Puthiyathura) indicated that many fishers own or have access to Android smartphones and are increasingly using commercial weather apps (e.g. Windy and Windfinder) that provide ‘wind maps’– graphical representations with animations showing wind speed and direction. These apps provide live dynamic visualisations of wind forecasts for all locations on the globe for 7-10 days in advance, and support zooming-in to large-scale maps of the local coast. These apps visualise wind speed through colour coding, and show wind direction through animated ‘particles’ like moving arrows or dashes. Amongst the fishers in Marianad and Puthiyathura,2 almost half of those interviewed mentioned the use of these apps. They are primarily used onshore either the day before or on the day of a planned fishing trip. Whilst such apps are worldwide services, and thus show forecasts for the Thiruvananthapuram coast (along with every location on earth), there is potential for such services to give the incorrect impression of providing a highly localised and precise forecast.

The Wind and Waves Service

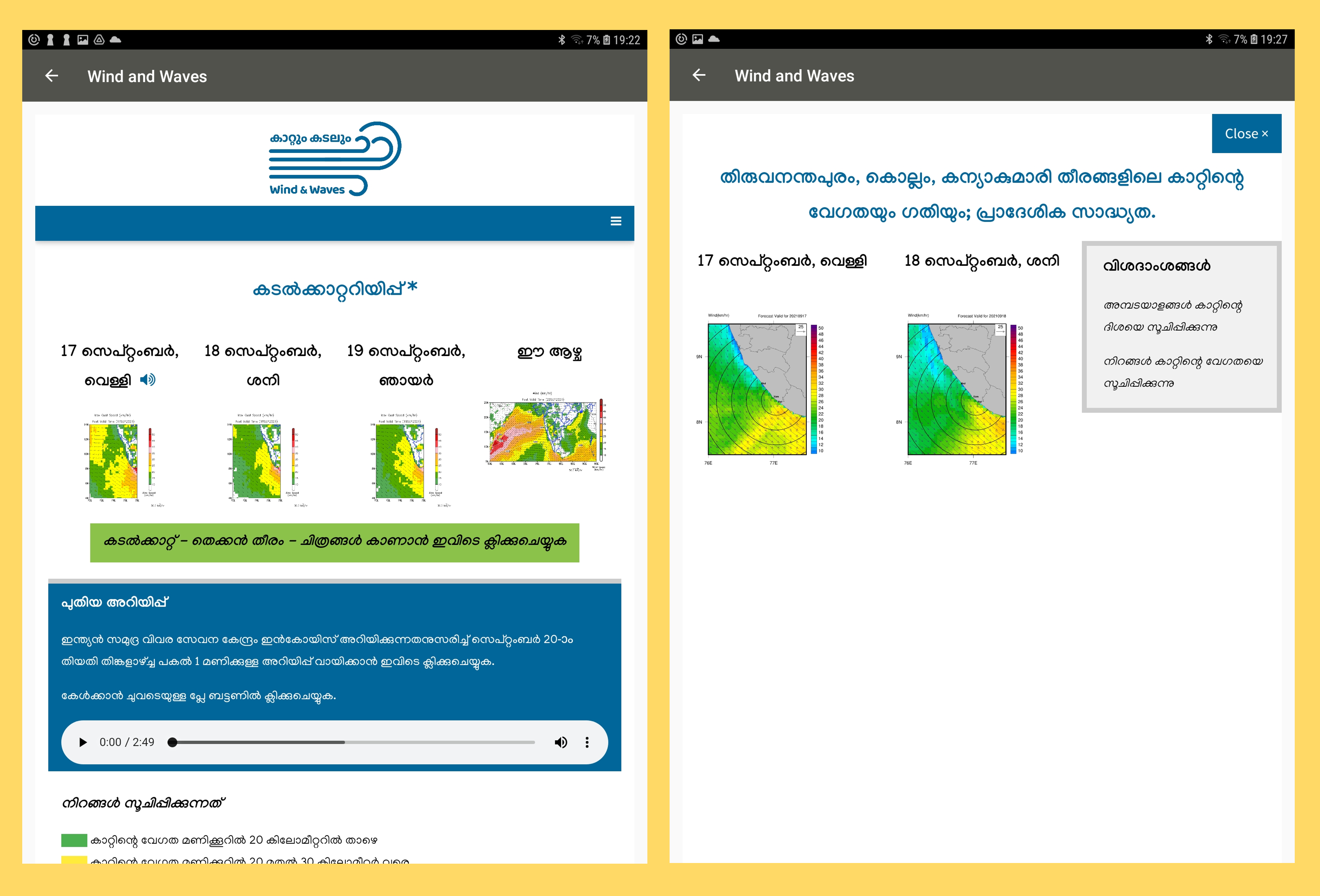

Based on our initial findings, our team explored a decentralised approach to providing forecasts that meet the needs of Kerala fishers. We designed and developed new ICT tools to support the co-production and communication of accurate weather forecasts. Arriving at an approach that fishers found useful was a joint effort, spanning key local organisations and agencies, and multiple mediums. We expanded our existing collaboration with Radio Monsoon,3 an online community radio station, to produce bulletins in Malayalam. These bulletins consisted of forecasts from different sources, collated by the experienced Radio Monsoon team with expert input from Cochin University of Science and Technology (CUSAT). Based on fisher needs, they released bulletins adapted for small boats twice a day and also offered a biweekly weather outlook. Cochin University of Science and Technology (CUSAT) also worked with us to produce and disseminate custom-made visualisations of wind speed and direction on the Kerala coast. Their team of scientists produced wind maps at three different levels of granularity–the first showing the entire Arabian Sea, the second showing the coastline of Kerala, and the third a ‘small grid’ visualisation focused on Thiruvananthapuram district.

Combining these new and existing ICT tools, we developed the Wind and Waves service, which distributes radio bulletins and wind visualisations through an Android application and a website with a responsive design. Having a responsive design means that the app displays well on computers, tablets and smartphones, which makes the site accessible to the greatest number of people with online access. The Wind and Waves app and website are intended to supplement and support existing means of communicating forecast information, including the previously available Radio Monsoon bulletins disseminated via internet radio. The Android application also builds on an existing Interactive Voice Response platform provided by GramVaani, an IIT Delhi-incubated company. This allows users to download Radio Monsoon bulletins when data is available and save for later listening, and also allows users to record their feedback on the bulletins via voice. In addition to the Android app, we also continued to provide the bulletins on free calls over a phone line. Fishers can either sign up with GramVaani to receive automated calls when new bulletins are available or call a number to receive a return call with the bulletin.

We launched the Wind and Waves app and website in May 2021, and asked a number of fishers in each village to regularly check the bulletins, either by downloading and using the Android application, accessing the website, or using the other means mentioned above, if these were not accessible for them. The team also used social media and WhatsApp messaging to disseminate and collaborate with local fishers’ collectives. We also provided local low-tech solutions such as loudspeakers and display screens in vital places where people usually gather.

The research team systematically collected fishers’ feedback on forecast quality, reach, and relevance, primarily through keeping paper logs for each boat. We are currently analysing the data and feedback received from fishers and sharing it with forecasters. We are also analysing boat logs and weather data for the period to gain a more robust picture of the accuracy and usefulness of the information sources. The radio bulletins continued to be well-used, but there has been growing interest in and enthusiasm around the wind maps, and a clear desire among fishers for these to continue to be provided. The first impressions from fishers regarding the accuracy of the wind maps are good. “The wind prediction on this webpage and what is happening right now are nearly identical. This is just what we require,” said one of the fishers we spoke to in Marianad. Early analysis to gauge the effectiveness of the different ICT tools we provided suggests that fishers preferred the Wind and Waves website rather than the app for accessing wind maps. This is because the app is currently not optimised for viewing graphics, being primarily designed for distributing audio and video files.

In short, our research so far has indicated that artisanal fishers highly value ICT for timely, accurate, and localised coastal weather forecast dissemination. The project indicates that decentralised production of the coastal weather forecast and its dissemination through ICT supports fishers in accessing the precise information needed for decision making. Our aim is that such tools will reduce the risk to artisanal fishers at sea in extreme weather conditions, and ensure sustainable livelihood at the time of growing climate-change-related uncertainty in weather.

About the Authors: Kate Howland is an Interaction Design researcher at the University of Sussex. In her research, she seeks to ensure that domain-experts and end-users have an active role in technology design. Her focus is on the design and evaluation of novel technologies for learning and communication in real-world contexts. She can be contacted via email: k.l.howland@sussex.ac.uk

Roopesh O. B. is a Research Associate in the School of Global Studies at University of Sussex, UK. He completed his PhD from the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, on “The Makings of a ‘Temple Public’: A Study of Modern Hindu Temples in Contemporary Kerala”. Roopesh does research in cultural anthropology, historical sociology, hindu temples, sociological theory and Indian religions.

Maxmillan Martin is a geographer. He’s a research fellow at the University of Sussex and a visiting researcher at the Advanced Centre for Atmospheric Radar Research, Cochin University of Science and Technology.