Sreejith delves into three of M. R. Renukumar’s illustrated stories for children, exploring how these rich portrayals of the turbulent lifeworlds of boys convey the complexities of gender, caste, and social marginalization for young readers.

Sreejith Murali

In many literary and visual art forms, portrayals of childhood have been poignantly used to articulate complex and nuanced social realities. However, while presenting narratives of childhood for children themselves, doing so is a uniquely challenging prospect, a challenge that M. R. Renukumar takes up in his writing for children. In this essay, I review three works for children by well-known Malayalam writer and poet M.R. Renukumar and explore the themes of boyhood, sites of childhood, and emotionality in these works. Nalaamklaasile Varaal and Aracycle are illustrated collections of short stories, and Podiyarikkanji is a storybook in itself. For me, the three storybooks opened up a world I am not familiar with but have heard about while growing up in Kerala (Bishop 1990). For others, they can be mirrors reflecting their lives in a sensitive portrayal. For children who are reading these stories today, they are also a peep into the past. Boys are central characters in these short stories, perhaps because the author is more aware of growing up as a boy, while other characters such as family members, friends–both boys and girls–teachers, and neighbours also have equal significance.

Sites of Childhood: Spatial and Temporal Elements

The author does not explicitly take up the trope of remembered childhoods that is common in Malayalam children’s literature, but there are indications that the stories are inspired by the author’s memories. The stories are presented as first-person narratives of the central characters who are young boys in their pre-teen or early teenage years. The boys’ experiences of lives take place in rural Kerala in a time and space where there are limited resources, though the exact period is not mentioned. The children mostly go to government schools, are from labouring families, and live in modest houses often constructed by the families themselves. Although the writer does not allude to the social identity of the characters, the socio-economic settings of the stories can be indicators that the central characters are from oppressed caste communities.

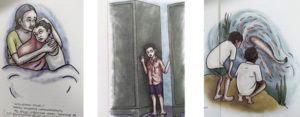

The stories open to the readers multiple sites of childhood including the home, school, spaces of play and leisure, parents’ workplaces, and the larger geographies where the stories are based. The space, environment, and social geography of rural Kerala is a recurrent theme and is itself a character in the stories. Most of the stories are located spatially in the riverine ecosystem, possibly along the Alappuzha-Kottayam stretch.1 Fishing is a common theme for the children who are active agents in the stories, where the elaborate processes involved in fishing with a rod are detailed, with the protagonists planning for the budget and preparing the bait. There is a general sense of wonderment, excitement and, at times, fear when catching the bigger fishes. At times, the river becomes the site of the struggle for a boy to catch a big fish while in other stories it is a site of play, and of teaching and learning how to swim. Besides institutional spaces like the school, these are the spaces where friendships are forged, adventures play out, and learning happens. These other everyday sites offer the readers a glimpse into the rich lifeworlds of children beyond school and home through highly contextualized representations of space and time. Nalaamklaassile Varaal and Podiyarikkanji are illustrated in colour with the characters portrayed with realism (Sreenivas 2016), especially the emotional joys and tribulations of growing up. The illustrations help vividly highlight the sites of childhoods–schools, pathways, rivers–that place the characters within the setting with ease; they add a layer to the narrative text. Portrayals of the young protagonists’ travels within the larger social geography opens up sites unique to rural Kerala–they are shown crossing the river to reach home from school, walking along a long village road to the hospital where they encounter their schoolmates, travelling in mud roads and crossing a stream where they meet a girl and her mother washing clothes, or travelling to tuition classes, and so on.

The story Enikku Manassilaavaatthathu (what I don’t understand) in Nalaamklaassile Varaal is set in the protagonist’s father’s workplace. The young boy goes on his first journey to the city with his father where he works in a bank as a thooppukaaran (sweeper). The boy is unable to understand the different incidents of the day. He is not aware of the hierarchy of labour in the bank and is unable to comprehend why his father is addressed in a certain way by the officers, and why his father accepts used clothes from a bank officer. He carries his doubt along with a sense of anger, shame, and sadness to his home where he questions his mother about it. In Podiyarikkanji, the protagonist rushes back home from school, worried about his sick father. After reaching home and knowing that his mother has taken his father to the hospital, he goes to the kitchen and tries to remember the exact procedure that his mother follows to make broken rice gruel and a side-dish. The site of the kitchen and the act of preparing food challenges the mainstream idea of masculine sites in the house. For the boy, the hospital is juxtaposed with his home as he remembers his stay in the hospital with a certain fondness as there was a fan, a bed to sleep on, and a washbasin to brush teeth. The sites are not just background settings but critical to how the stories emerge and unfold.

Boyhood, Emotionality and Relationships

Fictional accounts of childhood open up the possibility of exploring the everydayness of life through the eyes of children. Historically, boyhood within children’s literature is highlighted through masculine characteristics like adventurousness and mischief, giving little space to other emotions (Tribunella 2011). The boys in Renukumar’s stories are adventurous and inquisitive, but they are also sensitive, caring, reflective, and show emotional vulnerability. Their innocence is not in their ignorance of the social world of adults but in their making sense of it and in their overcoming of these vulnerabilities. Emotions and relationships with friends, family, and surroundings are also a big part of these narratives, with the author sensitively portraying the inner struggles of children growing up in marginalized social contexts.

The most nuanced aspects of these stories are often that of the father-son relationship. Different emotions like love, longing, hope, and fear are shared between the father and son. They are shown as sharing a tender emotional connect–though elements of the strict fatherly bond are alluded to in the text, fear or anger are never the dominant emotions. In Aracycle, while the protagonist yearns to learn bicycle riding, he is fearful of going against his father’s instructions. When his father gets him a new cycle, fear turns to excitement and joy. In other stories, the boys are aware of the difficult lives of their father and are careful not to make unfair demands of their parents. In Podiyarikkanji, the boy prepares food for his sick father and takes it to the hospital. Seeing his gesture of care, both his parents become teary-eyed, and his father remarks that his fever has disappeared. Mother-son relationships are also explored in the stories with much tenderness, and the mother is always the person the child turns to for emotional support. Renukumar portrays his male characters as displaying emotional vulnerability, tenderness, and care. These characters understand each other’s vulnerabilities and their portrayal redefines the boundaries of dominant masculinity.

Peer group interaction consists of boys and girls from different religious communities, and the emotional bonds between them that are stressed are qualities like sharing, understanding, and care rather than assertiveness (for example, in the story Choondacompany [Fishing Friendship] in Nalaamklassile). Noor in Aracycle tells the story of friendship between two boys. As a boy is gifted a fish by his friend, and the tiny fish dies the next day, his excitement turns to fear and sadness on losing the gift. The boys in these stories go through emotional ups and downs which they freely share with those around them. Unlike in normative narratives, those around them do not reinforce the toxic ‘boy code’ wherein boys are often violently taught to regulate emotions and their expression, moulding them into dominant masculine behaviour (Stahl & Keddie 2020).

Conclusion

Boyhood emerges from these texts through emotional relationships between adults and children, between boys and girls, and among a group of boys in the everyday lives of children in different sites like schools, home, and peer groups (Cann et al. 2020). There is a sensitive portrayal of boyhoods, tracing the everyday in rural Kerala during the last decades of 20th century. There are elements of innocence in some aspects of the boys’ lives, but since their characters are shaped within social realities, it is not a romanticised view of childhood innocence that is portrayed. These stories would transport the young reader to a fictional space, but one that is relatable depending on their own experiences of growing up. Not once does the author talk down to the reader in a prescriptive manner about how an ‘ideal’ childhood should be. Instead, there are values of friendship, care, and love embedded within the text. By situating protagonists in real-life settings, normative boyhood characteristics and stereotypes are challenged, and the socioeconomic setting of the stories describe the lifeworld of children who are usually left out in children’s literature. This set of books will be a valuable reading experience for children in their early teens, and even for adult readers. The flow of words and the illustrations transport the reader into the worlds of the children who tell their stories. As readers travel to the world inhabited by the narrator, we laugh, cry, empathise, and reflect as we follow the journey of the characters.

Books Reviewed

- Nalaamklassile Varaal [Snakehead fish in the fourth standard] (2019). Illustration: Aruna Allancheri. Thiruvananthapuram: Kerala State Institute of Children’s Literature. ISBN: 978-81-907460-5-2. Rs. 70 (Paperback/Colour)

- Aracycle [Half-cycle] (2019). Illustration: Sachindran Karaduka. Kottayam: Mambazham (A DC Books Imprint). ISBN: 978-81-264-7376-2. Rs. 99 (Paperback/B.W.)

- Podiyarikanji [Broken rice gruel] (2019). Illustration: T.R. Rajesh. Thiruvananthapuram: Kerala State Institute of Children’s Literature. ISBN: 978-93-88935-10-4. Rs. 40 (Paperback/Colour)

References

- Banerjee, Swapna M. 2010. ‘Everyday Emotional Practices of Fathers and Children in Late Colonial Bengal, India. In Childhood, Yout,h and Emotions in Modern History edited by Stephanie Olsen, 221-241. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bishop, Rudine Sims. 1990. ‘Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Glass Doors’. Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for The Classroom 6, no. 3.

- Cann, Victoria, Sebastián Madrid, Kopano Ratele, Anna Tarrant, Michael R. M. Ward, and Raewyn Connell. 2020. ‘The Men and the Boys, Twenty Years On: Revisiting Raewyn Connell’s Pivotal Text’. Boyhood Studies 13, no. 2, 1-8.

- Osella, Caroline, and Filippo Osella. 2006. Men and masculinities in South India. Anthem Press.

- Renukumar, M.R. & S. Kalesh. 2021. Allinjupuvillya Chila Paadukkaloru Perumazhayilum – Kerala Sahitya Akademi Puraskaram Nediya M.R. Renukumar Samsarikunnu [Some scars don’t dissolve even in mighty rains: Sahitya Akademi Award winner M.R. Renukumar speaks]. Published online in Samakalika Malayalam, 27 March 2021. https://www.samakalikamalayalam.com/malayalam-vaarika/essays/2021/mar/27/kerala-sahitya-akademi-award-winner-mr-renukumar-speaks-116795.html

- Shen, Lisa Chu. 2020. ‘Masculinities and the Construction of Boyhood in Contemporary Chinese Popular Fiction for Young Readers’. The Lion and the Unicorn 44, no. 3, 221-241.

- Sreenivas, Deepa. 2016. Illustrating Traditions: The Visual Order of Children’s Literature. Diotima’s: A Journal of New Readings 7, 21-34.

- Stahl, Garth, and Amanda Keddie. 2020. The Emotional Labor of Doing ‘Boy Work’: Considering Affective Economies of Boyhood in Schooling. Educational Philosophy and Theory 52, no. 8, 880-890.

- Tribunella, Eric L. 2011. ‘Boyhood’. In Keywords for Children’s Literature, 21-25. New York University Press.

About the Author: Sreejith Murali is a PhD student at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology Bombay. His research project is on the experience of education for dominant castes in South Malabar districts in Kerala in the late 20th century. He is also interested in educational policy, historical childhoods, children’s literature, and work on children’s libraries.

Acknowledgement: The author would like to thank Dr Divya Kannan for her helpful comments on an earlier draft of this article and for sharing readings on boyhood, son-father relationships etc.

One comment