This article discusses the need to study histories of female impersonation in popular Malayalam theatre and their role in nuancing our understanding of gender in and as performance

Shilpa Menon

“A tune, hummed in the bhairavi ragam, was heard offstage. The beautiful voice earned enthusiastic applause. As the source of the voice came onstage, the audience fell silent, seeing that it was a woman. It was unheard of for a woman to present herself onstage thus in Malayalam theatre. But it was not a woman; it was Shri. Ochira Velukkutty. Backstage, I myself was in doubt. A young beauty in the full bloom of seventeen.”1 (Sreekumar 2006:37)

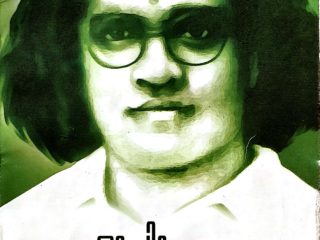

Who is this beauty that stunned audiences in the heady days of nascence of Malayalam theatre? This excerpt is a reminiscence by Sebastian Kunjukunju Bhagavathar, one of the pioneering actors of Malayalam theatre, about the first time he witnessed a performance by Ochira Velukkutty. Velukkutty was a “female impersonator” who was to become iconic in his role, among others, as the courtesan Vasavadatta in the pathbreaking play “Karuna”. The prevalence of men impersonating women onstage was by no means an uncommon event in early twentieth century South Asia. Studies have largely explained this trend as an effect of patriarchal constraints on women themselves appearing in public performances, a trend that disappeared as the modernization of aesthetics and performance cultures allowed women to take the place of female impersonators in theatre catering to the elites, rendering them a relic of times past (Hansen 2001).

There is much that this narrative erases, at least in the case of Kerala. For one, traditions of female impersonation continued to survive and thrive in various performance cultures that soon came to be considered as “low culture”. In Kerala, Velukkutty’s successors burst into primetime television as “female dupes” in comedy reality shows in the early 2000s. These were established artists who had long been touring towns and cities of Kerala as part of stage show samithis (troupes) hired to perform at various events and festivals. These actors came to be known for their naturalized portrayal of idealized female figures (the mother, the wife, the glamourous siren) in comedy skits. They marked a departure from the dominant comic trope of men performing as women, where the mixing of male and female gender cues on the same body was itself a source of humour. It is the public reaction to the female dupes’ vibrant presence in comedy reality shows, ranging from awe to repulsion, that drew my attention to these performers. Conversations with them, in turn, gave me glimpses of subaltern cultures of female performance that compelled me to problematize existing histories of female impersonation in South Asia. It is Ochira Saji, a long-standing female-role performer, who first told me about this legendary predecessor who came from the same town as him. Velukkutty himself was brought back into public memory by director Kamal in his 2013 film, Nadan, where he was played by Santhosh Keezhattoor. Keezhattoor then went on to perform as Velukkutty in the acclaimed one-man play Pen Nadan (female actor).

Writings on Velukkutty (Sreekumar 2006) and other artistic representations of his life indicate that the life of the female impersonator is a difficult one; a fact made evident by the “female dupe” artists I interviewed. Poverty, lowered caste status and lack of adequate recognition prominently characterize the life narratives of Velukkutty and his 21st-century successors. They are widely admired for their portrayals of idealized femininity and for being just like, or even better than, women themselves. However, as male-perceived bodies channelling femininity, they also become the objects of voyeurism, on the one hand, and moralistic censure on the other. Velukkutty’s various experiences of being harassed by male audiences are echoed by the “female dupe” artists, and intriguingly, by Keezhattoor as well (Dayabji 2018). Moreover, their acts of gender-crossing make them highly aberrant to Kerala’s conservative public culture. In the 1930s, Velukkutty’s portrayal of a desiring and desirable Vasavadatta was criticized as being lewd and inappropriate for respectable audiences, much as the female dupes are accused of performing vulgarity for television ratings. These two reactions–desire and repulsion–are less divergent than they seem. They are both ways in which audiences seek to “make sense” of these performers in a culture that only legitimizes femininity when it is performed by a body they recognize as “naturally” female.

I argue that these fragmented narratives and histories of female impersonation become important for the construction of a more expansive genealogy of female performance in Kerala, one that is based on a more nuanced understanding of gender. There is ample feminist writing exploring how our genders become part of our senses of self through a process of bodily discipline, where meaning is sutured to bodies through implicit and explicit constraints. This disciplining, and its connection to patriarchy, is most commonly studied in the case of “classical” feminine dance forms such as Mohiniattam, which was actively expunged of its textual and gestural eroticism to make it palatable as a performance of idealized, upper caste femininity in the mid-twentieth century (Krishna 2016; Devika 2007).

Even as these studies explore the disciplining and negotiation of femininity as an embodied accomplishment carried out in everyday life and in more spectacular expressions like dance, they fail to truly challenge the presumption that femininity naturally adheres to the body perceived or sexed as female. The impact that female impersonators have on the public sphere clearly indicates that the production and reproduction of norms of femininity take place through bodies that need not be understood as female. Therefore, by only looking at female traditions of feminine performance, we as researchers risk reifying a normative understanding of (female) gender as biological attributes corresponding perfectly with (female) sexed bodies. If we begin to think of gender as indissociable from cultural norms of masculinity and femininity, and as being fashioned through various kinds of performances, our genealogy of female performance must necessarily pay attention to the stories of Velukkutty and the female dupes.

The public dismissal of the comedy show performers as “vulgar” also reveals much about how certain performances of femininity that (are made to) reflect dominant ideals and elite values are held up as exemplary, whereas others, emerging from and remaining rooted in working class, Dalit-dominated performance cultures, are dismissed as being disreputable. As the inheritors of a long tradition of female impersonation, the female dupes suffer multiply because their art is marginalized in terms of cross-gender dynamics and because of its association with what is dismissed as “low culture”. By dismissing their presence merely as the evidence of “backwardness”, as only indicators of conditions where women still do not have access to public performance spaces, researchers too risk ignoring the complex history of female impersonation and embracing a form of feminist critique that is not adequately attentive to the intersectional dynamics involved.

References

- Devika J. (2007). En-gendering individuals: The language of re-forming in early twentieth century Keralam. New Delhi: Orient Longman.

- Dayabji, Roopa. (2018). Kannenno Kalamaan Mizhiyenno [Doe-eyed beauties]. Vanitha, Intl. ed. April 1-14 2018. Kottayam: M.M. Publications Ltd.

- Hansen, K. (2001). Theatrical transvestism in the Parsi, Gujarati and Marathi theatres (1850–1940), South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 24:s1, 59-73.

- Krishna, K. K. (2016). Gender and performance: The reinvention of Mohiniyattam in early twentieth-century Kerala. In Saugata Bhaduri and Indrani Mukherjee (eds), Transcultural negotiations of gender. Springer India.

- Sreekumar, K. (2006). Ochira Velukkutty. Thrissur: Kerala Sangeetha Nataka Akademi.

(Shilpa is a PhD student in anthropology at the University of Illinois at Chicago. She researches queer cultures and networks in Kerala, and can be contacted at shilpaparthan@gmail.com)