Abhayan G. S. and Rajesh S. V. write about findings from the ongoing excavation of an Iron Age burial in Kerala, delving into the minute details that could unlock important clues to past human settlements in the region over two thousand years ago.

Abhayan G. S. and Rajesh S. V.

Tracing back Kerala’s history with the helping hands of the discipline of archaeology, one can reach the onset of iron technology—a revolutionary advancement in humans’ use of tools. Even before this ‘Age of Iron’, stone tool-using people lived in Kerala. The shift to using iron artefacts is most evident in what is called ‘Megalithic’ or Iron Age burial remains across south India. These burials share many commonalities in terms of the types of artefacts buried with bodily remains and the architectural features of the burial itself, such as dolmens, cists, urns, and stone circles.1

Among them, the Kerala region features specific forms of burial architecture such as rock-cut chambers (vettukal-guha), umbrella stones (kudakkal), capstones (topikkal) and hood stones. Archaeologists see these burial structures as reflecting societal beliefs in life after death at the time, providing important insights into cultural and social hierarchies of the time. Excavating burials helps us answer important questions about the kind of skills, techniques, and technologies that societies had developed at a particular time and place in history. They also help us understand how different societies at the time were similar or different, and details of interactions like trade or conflict. However, common people in the present day perceive these remains differently: as the abode of ghosts, as the halting places of wandering sages in ancient times (hence the popular name muniyara), or as burials of immortals.

The Iron Age burials of Kerala are secondary in nature, which means that only some bone fragments are buried, not the full dead body. They contain burial goods, of which pottery, iron objects, and semi-precious stone beads are very common, and copper, gold, cereal grains, etc. are more occasional. The chronological range of Iron Age culture in Kerala is broadly around 900 BCE and 300 CE, as ascertained based on a series of radiocarbon dates obtained from excavations. This time bracket overlaps with the Early Historic period in South Asia (i.e., circa 300 BCE onwards), when written inscriptions begin to become available in the archaeological records. The excavations at Pattanam on the bank of the Periyar river reveal some hints of this connection.

Even though the burials are hidden beneath the ground, some kind of surface-markers like stone circles or capstones are usually visible above ground which helps to locate them even without an excavation. An excavation, however, helps to know more about the interred artefacts and the nature of burial. More than a thousand such burial sites have been reported through academic writings, newspaper reports, and social media posts from Kerala, and it is likely that many more are destroyed or unreported. Burial sites are located all over Kerala on almost all kinds of lateritic2 terrains, including in forests and sparsely populated areas. This raises the question: what had they been doing in these deeply interior places?

The burial pottery types show uniformity with other specimens of south Indian Iron Age culture. The semi-precious stone beads in these burials are definitely of non-local origin, which indicates the presence of long-distance trade at the time. Unfortunately, unlike burials, there have not been any archaeological discoveries so far of places of settlement from the Iron Age of Kerala. Hence, less is known about these ancient people’s ways of living, making it all the more intriguing. The little available evidence suggests that they were not mere hunter-gatherers, but played a significant role in a complex society. Based on these limited lines of evidence, it is possible that the people in these more isolated settlements produced spices or forest products for long-distance trade.

A giant leap in research may not always be practically achievable, especially in the field of archaeology. Small steps are often more helpful in making incremental additions of knowledge. In today’s age of advanced industrial manufacturing, minor changes in construction techniques might seem irrelevant. However, in ancient times, the limited development of materials and manufacturing meant that even small changes could indicate significant advances in how societies procured and processed raw materials for their use. With further research, these small details could potentially unlock important knowledge about how human societies changed over time. In this spirit, we draw the readers’ attention towards our recent work in the field of Iron Age in Kerala on behalf of the University of Kerala’s Department of Archaeology as part of the Kerala Megalithic Gazetteer Project (KMGP).

In the last decade, archaeological excavation and surface surveys by archaeologists like Ambily C.S., Harinarayanan S., and Haseen Raja have highlighted the scope of Iron-Age research based in the Pathanamthitta region. In 2019, a team of archaeologists under KMGP ventured to excavate a cist burial at Enadimangalam in Adoor Taluk of Pathanamthitta which was discovered by Harinarayanan. We spotted the tip of 3 stone slabs on the surface of a hillock covering a privately owned rubber plantation (see fig.1). Fifteen days of excavation at the site revealed a large cist with two chambers (see fig.2).

The cist shares many similar features with those that were revealed elsewhere, with two portholes 3 (one trapezoid and the other circular-shaped). A special feature of this cist is the presence of cot/bench inside each chamber. While cots carved in laterite are frequently seen in the rock-cut chambers of northern Kerala, cots inside cists are relatively rare, and in southern Kerala, this is a first. Twelve complete pottery artefacts were found in crumbled condition on the floor level of the cist. These can be considered as the original placement of burial offerings of the Iron Age burial event. Even though nothing was found inside these vessels, it is quite possible that some kind of perishable items were offered; some possibilities are food, beverages, clothes, or anything of that kind required for the deceased in their afterlife, as per belief.

In addition to this, we excavated a large number of broken potsherds or pottery fragments from the soil filling the burial. Closer observations on the pattern of distribution of these sherds within the cist filling indicate repeated use of the same cist for multiple burial events. The Megalithic burial tradition lasted for at least a thousand years; presumably, such elaborate burials might not have been done for each individual of the society. At least one burial, probably of a chief, could have happened once in a generation. Considering this frequency, the number of burial monuments is relatively low. This strengthens the hypothesis of repeated use of a burial monument for several generations. Radiocarbon dates from other Megalithic burials of south India also support the conclusion that burials were likely reused in that time period and region. In addition, it is interesting to observe a distribution pattern of at least 20 cist burials in a circumference of roughly 10 km on the landscape of Enadimangalam. All of them are isolated from each other at least by a kilometre, suggesting a wider distribution of settlements and continuous use of these limited numbers of cists for multiple burial activities.

One of the main objectives of the Enadimangalam excavation was to understand how cists were constructed during the Iron Age. For this, our team used a specific technique to dig trenches into the soil as we excavated. Conventionally, archaeologists only excavate inside a buried cist, which means that features outside the cists can be missed out. To overcome this, we adopted a trenching method that extends the trenches wherever essential to know about many important cist construction activities (see Fig. 3). The stratigraphy (layers of earth) reflected on the cut sections of the soil gave us an idea about the processes associated with the ancient people’s activities. Through this technique, we were able to infer the possible sequence in which the slabs of the burial were placed. We noted that small supporting stones were used to place the slabs. We also discerned the methods used to cut the stone for the burial and to dig the pit.

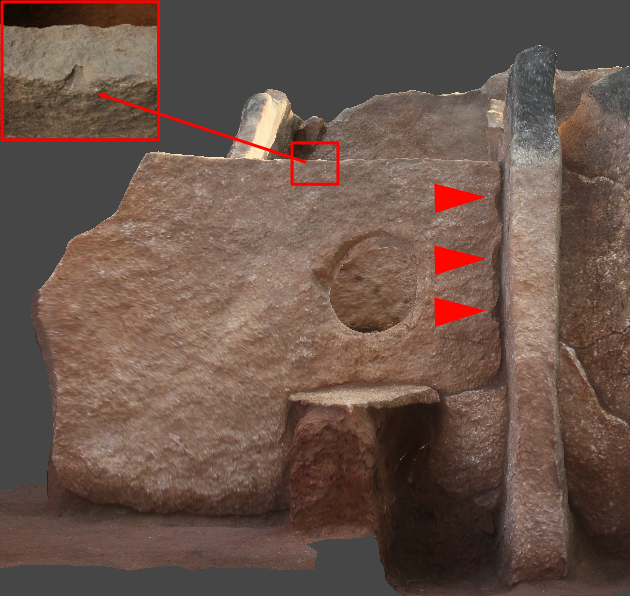

The portholes found in Iron Age burials provide excellent insight into how well people then were able to shape hard stones like gneiss. But it is interesting that they have not attempted to shape the rest of the stone slabs comprising this particular cist. We noted an important exception: three large flake marks on one slab (see fig. 4), resulting from heavy hammerblows, indicates that it alone was shaped to fit in with the adjoining slab. We also observed a series of U-shaped wedges on the upper portion of one of the slabs (see fig. 4), and identified that these stone cuttings were made not during the Iron Age, but for the reuse of these stones in a later era. Similar cuttings in other Iron Age constructions have, until now, been considered by archaeologists as the stone-cutting technique of Iron Age societies. Our finding with this burial counters this long-standing consensus .

The KMGP team continues to study the site at Enadimangalam, including radiocarbon dating and detailed comparative study of pottery, to shed more light on the life of Iron Age people in the Pathanamthitta region. We would like to highlight here, just how important focussed archaeological investigations on the Iron Age of Kerala are to know more about the lives of people of the time. Our findings so far raise important questions for further research, and shed new light on the Iron Age in South Asia.

We acknowledge the University of Kerala for funding, the Archaeological Survey of India for granting permission for the excavation, and the Kerala State Department of Archaeology for forwarding the proposal. We thankfully acknowledge Shri. Sivankutty Kalanjoor, the landowner of the site, for generously allowing us to excavate on his land. The immense support and enthusiasm shown by the villagers of Enadimangalam were remarkable.

Further Readings

- G.S., Abhayan, S.V. Rajesh, Akinori Uesugi, Preeta Nayar, B.S. Mohammed Muhaseen, N. L. Sulal, K.G. Archana, R. Harinarayanan, Ananthu V. Dev, K. Muhammed Fasalu, P. Soorya, K.S. Arun Kumar, R. Haseen Raja, S. Kumbodharan, M.S. Sujanpal, and M.S. Sandra. 2021. ‘Megalithic cist burial excavation at Enadimangalam in Kerala and its implications in cist burial architecture and burial practices’. Archaeological Research in Asia 27: 100293 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ara.2021.100293

- Abhayan, G.S. 2018. ‘Iron Age Culture in Kerala, South India: An Appraisal’. In Iron Age in South Asia, South Asian Archaeology Series 2, edited by Akinori Uesugi, 145-188. Osaka: Research Group for South Asian Archaeology, Archaeological Research Institute, Kansai University.

- Darsana, S.B. 2010. ‘Megalithic Burials of Iron Age-Early Historic Kerala: An Overview’. Man and Environment 35 (1): 98-117.

About the Authors: Drs. Abhayan G. S. and Rajesh S.V. are both Assistant Professors at the Department of Archaeology, University of Kerala, Kariavattom Campus, Thiruvananthapuram. Abhayan G. S. (abhayangs[at]gmail[dot]com) specialises in zooarchaeology and ichthyoarchaeology, and Rajesh S. V. (rajeshkeraliyan[at]yahoo[dot]co[dot]in) specialises in ceramic studies. Both are currently working on the archaeology of the Iron Age in Kerala and the Indus Civilization in Western India.

It may pointed out that there are two villages with similar name, both in Tamil Nadu, the one in Vizhpuram District and the other in Nagapattinam District. The word enathi( എനാതി) means barber caste as per Malayalam lexicon Sabda Thara vali. It also means military chief. So the place might be a settlement of barber community or mercenary community