Aathma Dious argues that Malayali filmmakers have failed to move past popular—often stereotypical—tropes when it comes to representing second and third generation NRIs, and urges for a nuanced ‘Gulf-kutty’ in Keralan literature and cinema.

Aathma Nirmala Dious

Many Thursdays of my life were spent at Eldorado Cinema on Abu Dhabi’s Salam St. We would be one of many Malayali families in the crowd, waiting for the doors to open so we could go fill in the seat detailed on the paper slip we got at the front counters, to watch the newest Malayalam film that had arrived at Abu Dhabi’s shores weeks after its release in Kerala. Watching Malayalam Cinema at this cinema was my first experience of the big screen, which ignited my love for cinema.

Even when visiting my grandparents in Thiruvananthapuram for holidays, going to the cinema was a family event. In 2015, Alphonse Puthren’s Premam (2015) came to screens and became one of the biggest hits that year. At the beginning of the movie, there is a scene that is still clearly in my memory: a boy in sunglasses and fancy clothes interrupts Mary’s walk home from school and talks of being the child of uncaring Malayali expatriates in Ras Al Khaimah, in an attempt to gain her attention and sympathy.

The punchline is that this boy’s story gets exposed as a lie by a passerby and the sunglasses were not enough to fool Mary’s father, who ends up beating him. Even years after watching Premam, I remember sinking into my scene, cringing as everyone around me laughed at this NRI child on the screen. It almost felt like they were laughing at me. The boy’s idea of an NRI gulf kid was one that is lonely, a child that had a father obsessed with business, a mother who parties everyday and seems extravagant (not in a good way). All of it was a mockery.

Of all the films I watched as a child, I can count on my fingers those that were about the Malayalis in the gulf. More pressing was that there were barely any that featured Malayalis like me: children that were born pravasis or became them at a young age—the second generation NRI children, popularly referred to as the “Gulf kutty” when visiting relatives in Kerala. If by chance, someone like me appeared, like in Premam, I am laughed at.

The “Gulf” is referenced at least once in contemporary Malayalam Cinema since the 1980s but in spite of the three decades that have passed since, the industry has yet to do justice to its diaspora in the Gulf, especially the second and third generation of Gulf-Malayalis. Most movies primarily focus on the generation that immigrated from Kerala–the pravasis themselves, like my father, and sadly, they often slip into using tropes. Take, for instance, Pathemari (2015), a historical fiction drawing from the history of the Gulf Boom from Kerala to tell the story of Narayanan (Mammootty), a Malayali migrant worker who arrives in UAE in the 1960s by a dhow to help his family. While the film does a great job of showing a historical timeline of the early arrival of Malayalis to the UAE, its fallacy is that it relies on the selfless breadwinner trope and blames Narayanan’s family for not appreciating his sacrifices.

Another trope in Malayalam cinema is the “rich white-collar job NRI” stereotype that meets the “pride comes before a fall” storyline. Fahad Faasil plays Dr Kumar, a doctor who is also a playboy, in a film that is an example of this intersection: Diamond Necklace (2012). The movie starts with his fall when he gets himself into financial and romantic trouble after maxing out his credit cards on his expensive Dubai lifestyle and ends with him learning the value of minimalism and tradition. It stems from the assumption that Malayalis abroad are automatically rich, and, in turn, think of Kerala as “beneath” themselves.

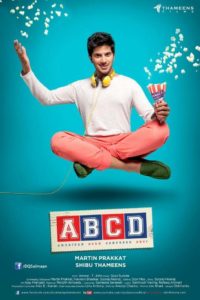

The stereotype of the wealthy pravasi has, since, birthed a child: a caricature that is the “the spoilt non-resident Indian (NRI) child”. The child is either from the US or Dubai–Malayalam cinema’s favourite stereotypes to make a punchline. Premam’s scene is an excellent example. If the movie centres on the NRI child, the follow-up trope is them learning a lesson in humility from their ‘naadu’- Kerala. A film that uses this as its main plot point is Martin Prakkat’s ABCD, in which Dulquer Salmaan plays Jonas, written to be the spoilt, westernised Malayali-American son of rich Malayali-Christian parents.

The film’s name, which is the popular internet acronym for “American-Born Confused Desi” is used here as an underhand jab to mock Jonas’ identity. When in the US, Jonas is a man of decadence; avoiding prayer, clubbing and playing public pranks. He is anything but a “good Malayali boy”, and that won’t do. Jonas then gets sent with his cousin Korah (Jacob Gregory) back to Kerala and their credit cards get blocked by his father, who tells him to fend for himself. While the story takes an inventive turn with Jonas and Korah gaining media attention for living simply, it insists that the NRI child is only good for a story that knocks them down a peg or two.

Salmaan plays a similar role in Ustad Hotel: Faizal, the son of a businessman in Dubai who gets stuck in India and ends up living with his grandfather who runs a restaurant. Once again, the story focuses on his coming of age, as he works in his grandfather’s small shop and sacrifices his old life for a new one, saving and preserving the culinary legacy of his grandfather. While similar to ABCD in that it is an excellent feel-good family movie that gives the hero a happy ending, the spoiled NRI child remains the starting point. Interestingly, Ustad Hotel is written and directed by Anjali Menon, who is a Malayali who grew up in Dubai. While I admire her storytelling, I was saddened that she leaned on the trope of the spoiled NRI gulf kid. If anything, I would expect her to push against the narrative.

There are many more films I can delve into, but the point is that stories of NRI gulf kids seem to not be worthy of the screen (or the page) unless we are privileged brats who are sent back to be taught a lesson. It rendered us one dimensional as if we are blind to our privileges and any trauma experienced by these characters is rendered invalid—even silly—or shown as character growth. These films appeal to the Malayali back in Kerala, who believe in these stereotypes or the Malayali immigrant parents who are too attached with maintaining their children’s connection with “home”. Growing up middle-class in the gulf did afford me many privileges, especially when compared to those working as manual labour or in the domestic service sector. However, to be stereotyped as wealthy, egoistic and spoilt, even among our own relatives, is often inaccurate and diminishes the complicated circumstances we encounter in being temporary residents in the GCC.

Watching Malayalam-language films in Eldorado Cinema, renting them from cassette shops, on TV channels that featured popular films during festivals, and now on online streaming services is what connects me to Kerala. Cinema has always been a way to access a reference point to my “Malayali-ness” since I can speak and understand Malayalam. The films I watched and my parent’s references to the films they wanted in the 80s-90s made up a big part of my Malayali identity. Malayalam cinema is important to me because it made up for the lack of relatable characters in Hollywood and other film industries. However, I do not want to be reduced to the moral of a story or the butt of a joke. I deserve nuance and proper representation.

The one film that has come close to getting it right would be the box-office hit Jacobinte Swargarajyam (2016), written and directed by Vineeth Sreenivasan. The movie is based on the real-life story of the Zacharia family, who have to rebuild after being wrecked with debt during the 2008 financial crisis. The narrator is the oldest son, Jerry (Nivin Pauly) who abandons his dreams to take on the responsibility of repaying his father’s debt.

Sreenivasan’s success here comes in not relying on stereotypes and this may be because the script and direction were informed by his friendship with George Zacharia—the real-life Jerry. This shows that it’s not about having personal experience, but rather a writer who respects the story and does the research. My favourite character in the movie was not Jerry, but Abin (Sreenath Bhasi), the third Zacharia child, who is a great example of a nuanced gulf-kid character. In contrast to the responsible Jerry, Abin is a hot-tempered musical twenty-year-old boy. What makes him interesting is that he is a college dropout who was expelled for fighting, which is a rare storyline for an expat character that grew up in Dubai.

One would expect the film to villainize him, given that many Malayalis (especially those in diaspora) excessively prioritize higher education as the only path to success. Instead, the film empathises with him and explores him as a protective sibling with skills that are helpful despite his reputation, without slipping into cliché. My favourite example of this is Abin taking their mother’s wrath for an alcohol stash that belonged to Jerry. When Jerry asks him why he took the blame, Abin jokes that their mom can take only one disappointing son.

The expected “progress” for Abin would be for the writers to make him return to university and become “responsible”. In an unconventional turn, his story ends with Jerry encouraging Abin’s musical career after being pleasantly surprised at his performance at an open mic. It’s an ending that feels true to the character and believable to the audience who watched him.

While still a feel-good story, Abin is the kind of nuance I want from those making film and literature with portrayals of Gulf kids. Malayalam cinema needs to pull itself up and invest in the story of its diaspora, either by working with Gulf-Malayali writers, directors, actors and filmmakers or doing the research necessary to tell authentic stories about the Gulf’s pravasis. Not to mention, we need more stories that centre on migrant Malayali women like my mother or myself; the examples I analyze centre on men, reflecting a gender disparity on the stories told about the Gulf.

If Pravasis can be afforded nuance in movies such as Arabikatha (2007), Take Off (2017) or Pathemari (2015), why not the Gulfkutti too? For once, I want to sit in a cinema, ready to watch comedy in my mother tongue where I am not its punchline.

About the Author: Aathma is a (Gulf) Malayai writer and poet who grew up in UAE, where she lives and works on South Asian-Gulf migration narratives. She recently graduated from NYU Abu Dhabi with a BA in Literature and Creative Writing and has published poems, short stories, and personal essays.

A very well expressed narrative, true to its content, as it comes directly from a Gulf kutty, apparently a very intelligent one too. Something long pending to be told, Aathma deserves appreciation and “Well Done”. The subject deserves to reach a wide audience and ‘Ala’ will do that for sure. Congratulations to Ala for providing the platform to the well deserved and hereby express the reader’s gratitude too.

True. In most of the films “Gulf Malayalees” are projected as caricatures. They are caricatured as snobbish and worthless NRIs except in a few movies like Jacobinte Swargaraajyam, etc. Yes, it’s high time, the movie makers look towards the screen play writers who have first hand experience of the middle east.

Loved reading this and the other story “Vathil”. Being a fellow NRI who spent her entire childhood back in the Gulf, I can totally relate to this. Looking forward to more such amazing content. Keep it going😃