Drawing from the translation of an anonymous, first-hand account of Vasco da Gama’s historical visit to present-day Kerala, B. Prabu gives us a snapshot of the events that eventually determined the course of European colonialism in the Indian subcontinent.

B.Prabu

A Journal of the First Voyage of Vasco da Gama in 1497-14991 is a travelogue originally written in Portuguese by an anonymous author who had accompanied Vasco da Gama. Using E. G. Ravenstein’s English translation, I summarize the pages in the manuscript which convey the experience and perceptions of da Gama in the region today known as Kerala.

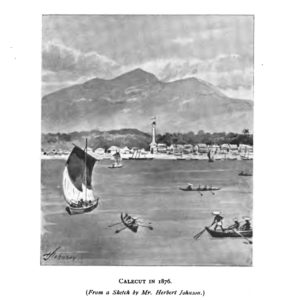

Throughout the voyage, da Gama tried his best to establish a good relationship with kings, chiefs, common people, local merchants, and also with the Muslim (Moor) merchants on the African Coasts and on the islands. After eleven months of journey, he landed on the western coast of the Indian peninsula, in present-day Kerala, on May 20, 1498. Here, Gama was given a warm reception by the Zamorin (samoodiri), the ruler of Calicut. Driven by his commercial interests, da Gama made attempts to understand the ways of the land and its people. In this regard, this text provides a European eyewitness account of Indian courtly culture and south India’s socio-economic and religious conditions at the turn of the 15th century.

Throughout the voyage, da Gama tried his best to establish a good relationship with kings, chiefs, common people, local merchants, and also with the Muslim (Moor) merchants on the African Coasts and on the islands. After eleven months of journey, he landed on the western coast of the Indian peninsula, in present-day Kerala, on May 20, 1498. Here, Gama was given a warm reception by the Zamorin (samoodiri), the ruler of Calicut. Driven by his commercial interests, da Gama made attempts to understand the ways of the land and its people. In this regard, this text provides a European eyewitness account of Indian courtly culture and south India’s socio-economic and religious conditions at the turn of the 15th century.

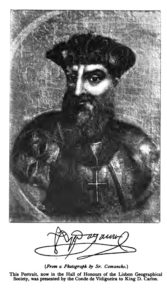

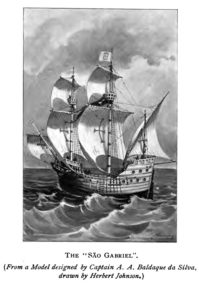

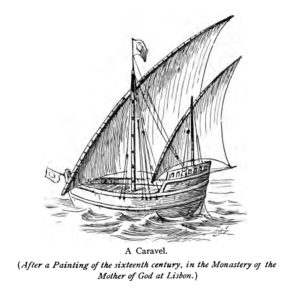

Vasco da Gama started his voyage towards India with the support of Dom Manuel (r.1495-1521), the king of Portugal. His journey started from the coastal village of Restelo near Lisbon in Portugal on Saturday, 8th July 1497. As the captain-major of the journey, Gama commanded four ships towards India, filled with around 170 men. The ships were S. Gabriel, the flag-ship commanded by Vasco da Gama; S. Raphael, commanded by his brother Paulo da Gama; Berrio, commanded by Nicolau Coelho; and a store-ship commanded by Goncalo Nunes.2

Vasco da Gama’s Arrival in South India

Before arriving in (present-day) Kerala, da Gama and crew stopped at the city of Malindi on the eastern coast of Africa. There, he was received well by the king, who sent with him a navigator who was familiar with the route to India. This took him one step closer to being the first European to successfully reach the Indian subcontinent by sea. In Malindi, for the first time, he met four Indian merchants. He misperceived that they were Christians; historians believe that he may have observed the worship of Krishna. On 24th April 1498, he started from Malindi, and after 23 days of journey, Gama and his crew reached Kappad, a coastal town in Kerala, on 18th May 1498.3

Moving onward from Kappad, on May 27th, da Gama anchored his ships at Pantharini-Kollam. According to the travelogue, Vasco da Gama was given a royal reception by the governor (alcaide) under the order of the Zamorin.4

On 28th May, Vasco da Gama went to Calicut to meet the Zamorin. He made his crew dress in their best, and they were given a grand reception attended by the governor’s brother, with the men beating drums, blowing anafils and bagpipes and firing match-locks.5 There was a large crowd of local people who followed da Gama and his crew. The author notes that they took him to a church ‘as large as a monastery’.6 In front of the church they had installed a pillar made of bronze, and ‘on the top of it was a bird, apparently a cock’.7 He noticed a painting image which had ‘its teeth protruding from the mouth, and four or five arms’.8 Within the sanctuary stood a small image which the people said represented Saint Mary. According to the translator, Ravenstein, the visitors likely misperceived the temple of the god Subramanian as a church, goddess Mariyamma as Mary, and Hindus as Christians.9

The text lists interesting observations about the appearance of the people. The author observes that the men are of a tawny complexion, and grow their hair long, with beards and moustaches. Some of them were tonsured, leaving only a tuft of hair on their head.10 The priests, called quafees, had marked their forehead and other parts of their body with white earth, and also wore some threads crossing their body. Only they could enter into the inner part of the ‘chapel’.11 About women, the author has recorded that they were ‘ugly’ and ‘small in stature’. They wore much jewellery made of gold on their ears, neck, arms, and toes. They did not cover their upper body, but over the lower part, wore fine cotton cloth. The author notes that though they seemed covetous and ignorant at first, in close quarters they have shown their good character.12

Vasco da Gama and the King of Calicut

After entering the gate of the palace to meet the King, da Gama had to pass four doors.13 The candlelights in halls were bigger than those the Portuguese had ever seen in his country. Unfortunately, the author does not make any mention about language, literature, songs and dance-forms that had been developed in the court of Calicut.

Before the Zamorin, Vasco da Gama announced that he was a royal ambassador for Dom Manuel, the king of Portugal.14 He explained that for the last sixty years, predecessors of the king had annually sent out vessels to discover a route to India, to no avail. The king had funded da Gama’s voyage with orders that he would be beheaded if he returned without finding ‘the king of the Christians’.15 Amid such political pressure, da Gama had come to India in search of Christians and goods.16 He told the people of the Zamorin’s court that his journey was ‘in search of Christians and spices’.17 Interestingly, da Gama’s gifts to the Zamorin—’twelve pieces of lambel (cotton cloths), four scarlet hoods, six hats, four strings of coral, a case containing six wash-hand basins, a case of sugar, two casks of oil, and two of honey’—were considered to be very poor in quality at the Zamorin’s court.18

Describing food and hospitality, the author notes that the Zamorin and the people were generally chewing betel leaves with areca nuts. The Zamorin in his left hand usually held a very large golden cup (spittoon) to spit the remains of the chewed betel nut.19 In the palace, da Gama and his crew were served fruits that they had never seen in Portugal. One fruit resembled a melon, and another resembled the fig—Ravenstein notes that these fruits might have been jackfruit and banana respectively.

During their visit, the Zamorin asked da Gama about the commodities found in his country. Da Gama replied that there was an abundance of corn, cloth, iron, bronze, and many other things of value.20 Subsequently, the king granted da Gama the permission to ‘land his merchandise, and sell it to the best advantage’ in the region [p.63].

Political Tensions and da Gama’s Return

From this point onwards, the travelogue explores the political intrigue and conflict that followed. The Zamorin’s permission turned out to be deceptive; da Gama and his crew were imprisoned in Pantharani while returning to their ships, likely with the aim of seizing the ships. But da Gama had anchored his ships far away from the seashore as a precautionary measure, foiling the attempt. The Zamorin demanded that da Gama land the goods from his ship in order to be released, and da Gama relented.21 The travelogue notes da Gama’s opinion that the ‘Christian’ king was influenced by the Muslim (Moor) officers and merchants, who saw the Portuguese arrivals as rivals.22

After the incident, da Gama was careful to avoid visits to the land for fear of imprisonment. But he devised a plan for trading under these conditions. A person from each ship was dispatched one after another to the city to sell and buy goods to avoid imprisonment en masse. All of his men were ordered to have their turn, and some of them were also detained on land. In the meantime, many of the local people and local sellers began coming over by boats to da Gama’s ships, anchored offshore, to trade with them. Da Gama imprisoned some among them and sent a letter to the Zamorin, asking for the mutual release of prisoners.23 The king accepted da Gama’s conditions and released the prisoners and his goods. But the issue was never resolved—Da Gama took all the prisoners from Calicut to Portugal to train them, with the aim of using them in subsequent voyages to establish a cordial relationship with the king of Calicut.24

Finally, da Gama and what remained of his crew left for Portugal, taking prisoners and a letter he had received earlier from the Zamorin to the king of Portugal, which stated:

Vasco da Gama, a gentleman of your household, came to my country, whereat I was pleased. My country is rich in cinnamon, cloves, ginger, pepper, and precious stones. That which I ask of you in exchange is gold, silver, corals and scarlet cloth.25

Gama’s journey back to Portugal took place through the Compia region (Cannanore, now Kannur) under a ruler the travelogue refers to as the ‘Biaquotte’ (identified by Ravenstein to be Cotelery raja).26 Further on, he reached Anjadiva Island (near Karwar in present-day Karnataka) on September 20, 1498. He purchased ‘boat-loads of green cinnamon-wood with the leaves still on’.27 There he found the ‘Christians of India’ calling the God ‘Tambaram’ (likely tamburan, lord/master in Malayalam).28 On Friday, Oct 5th 1498, he left Anjadiva, and crossed the Arabic sea. After three months of journey, he reached a city called Magadoxo (Mogadishu, present-day Somalia).29 The travelogue ends abruptly on 25th April 1499, the day they had reached the Rio Grande (Bissagos Island, on the western coast of Africa).30 But Ravenstein, the translator of the text, tries to reconstruct an account of the full journey by referring to other contemporary sources.

On July 10 1499, Nicolao Coelho, one of da Gama’s commanders, reached Cascaes near Lisbon in Portugal. The exact date of Vasco da Gama’s arrival in Portugal is not noted in the travelogue. Da Gama and his brother Paulo da Gama stayed at Terceira island in the Atlantic Ocean for some time to improve the health of the latter, who had been infected with the disease. But Paulo da Gama died there, and Vasco da Gama had to bury him at the island itself. This slightly delayed Vasco da Gama’s arrival at Lisbon, and he likely arrived on 29th August 1499.31

Subsequently, in March 1500, king Dom Manuel sent 13 ships under the command of Pedro Alvares Cabral to India. Using da Gama’s information, Cabral reached Calicut on 13 December 1500. In 1502, Vasco da Gama was made admiral in the Portuguese naval forces, and made his second voyage commanding a fleet of ten ships and ten flotillas to India. In 1503, he returned to Portugal having formed alliances with the kings of Kannur and Cochin against the Zamorin and the Moors. In 1524, he was made Viceroy within India’s Portuguese regime by King John III, arriving in Goa and initiating many administrative reforms. Da Gama died at Cochin on 24 December 1524. In 1538, his body was taken to Portugal and buried. Vasco da Gama’s discovery established the trading monopoly of the Portuguese over the Indian Ocean waters for a century.

About the Author: Dr B.Prabu is a guest faculty member of the Department of History, Bharathidasan University, Thiruchirappalli. He can be contacted at drprabubl@gmail.com.

One comment