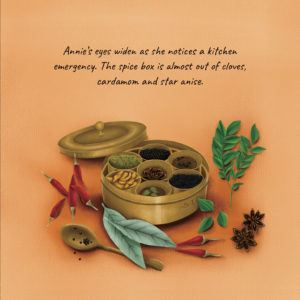

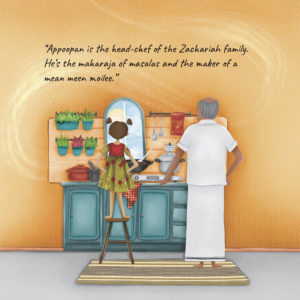

Filled with illustrations as colourful and flavourful as the spices it describes, A Little Spice Is Extra Nice is the story of Little Annie and her dear grandfather Appoopan, set in Mattancherry. We sat down with Sruthi and Sanjana—creators of the book—to discuss their work and the exciting genre of kid-lit.

Sruthi Vijayan and Sanjana Ranjit

Ala: What motivated you to work on a book for children? How did the idea come about? Were both of you involved?

Sruthi: Ah! So it all started with a phone call. It was at the beginning of the national lockdown—back in March 2020. Sanjana and I have been friends since college. It was an anxious call—the kind we made to friends and family—terrified and barely grappling with what was happening around us. At some point on that call, Sanjana mentioned that she was illustrating every day to calm her nerves. I always knew she would make a fantastic children’s book illustrator—even back in college, her art was warm and whimsical. So, one thing led to another, and we decided to write/illustrate a children’s book. I won’t say that the idea came out of nowhere but we did find ourselves finally at the place to write this.

I’m a photographer and all of my work had come to a complete standstill at that point and Sanjana was at the end of her maternity break. I cannot stress this enough—thanks to the privilege of having a roof over our heads, we could finally put in the time required to make this book. I’ve had experience writing and photographing travel stories in the past but I hadn’t written for children before. Sanjana is the more experienced one—she has been creating illustrations and graphic design work for a while now.

In retrospect, we laugh at our naivety; kid-lit is a very hard genre to master. What we thought would take a month at the most took us several months in the end. In part, because we were navigating this whole thing by ourselves—we made plenty of mistakes but we’ve learned so much and we are so thrilled that we have a book in our hands with our names on it.

In our case, the book was a collaboration. We birthed the idea together. I wrote and Sanjana illustrated but we consulted each other on almost everything. Sanjana also brought in her expertise with Kerala cuisine and nuances in language, etc., which was crucial to the book.

Ala: Tell us a little more about the process of writing and illustration? Is the text written first and later illustrated, or do both happen in tandem? How do you both work together?

Sruthi: The first thing to be addressed—we are a first-time author/illustrator duo so our approach differs from how the industry works.

The industry operates this way: assuming you have zero contacts—Sanjana and I knew no one in publishing—you submit a manuscript. If the publisher likes your manuscript, they assign you an illustrator. Sometimes, illustrators are writers themselves, so they’ll send out a rough sketch of characters/scenes. Usually, the illustrator and writer do not collaborate till the final manuscript is ready. Of course, there are exceptions to this process.

Our process was slightly different.

Once we landed on the idea, I wrote a rough draft. Sanjana started with rough character sketches which further helped me build the writing. Our characters travel through Mattancherry, so it was important to create distinctive visual settings. Once we had a fairly evolved manuscript (closest to the final draft you see) Sanjana built on the rough sketches. We completed the book. We looked up children’s book publishers. Our publisher, Talking Cub (an imprint of Speaking Tiger) had just won an award for one of their children’s books. So, we wrote to them, and then a week later they told us they wanted to publish our book. This is what worked for us, but isn’t a guarantee for anyone else.

Ala: At first thought, spices seem to be a matter for adults, and yet the topic works so beautifully in this book for children. What made you think of spices for a children’s book?

Sruthi: Before writing this book, I believed that certain topics were ‘too’ adult for kids. But when I looked at the publishing world—I learned very quickly that I had the wrong idea. Currently, the most loved books across the world talk about uncomfortable but necessary truths—racism, body image, gender fluidity, and diversity. So, in that regard, our book doesn’t deal with any complicated topic. It’s simply a book about spices.

Coming to our story, there are several reasons why we chose spices. First and most importantly, they say write what you know about. For Sanjana and me, our connection to food is deep. Food has such a deep-rooted cultural and familial significance which we wanted to introduce to young readers.

Secondly, learning to cook gives you the independence that you may not value as much when you are younger. As an adult, I now ask myself why it wasn’t mandatory education for children of all genders. It’s a fantastic life skill we all underestimate but ultimately need.

And finally, once Mattancherry became the setting of this story, the logical conclusion was to write about spices, owing mostly to Mattancherry’s spice history, but partly to the illustrative potential of the topic and how integral spices are to Indian cooking.

Ala: What made you set the book in a space like Mattancherry? What about the specificity—as opposed to India or Kerala—appealed to you both? Did it also have something to do with either of your personal histories?

Sanjana: Growing up in a Malayali-Tamil family, food from both cultures played a big role for me. So I had an early introduction to understanding different ingredients and their origins. For example, a Malayali fish curry smelled, looked, and tasted different when compared to its Tamil counterpart. We had different spice duppas [containers] for each. At 21, when I left home for work and missed home-cooked food, I had no other choice but to make my own pantry of spices. That is when I understood how each and every ingredient played a big role in adding flavour to the dish. For example, who would have thought a pinch of fenugreek to moru curry made all the difference? Spices being an essential ingredient in Indian cooking, my visits to Mattancherry have been inspirational. It is like a Mecca of spices and colours. The historical significance and the overall energy of the place were perfect for our book.

Sruthi: I’m a photographer and I visited Mattancherry as a part of my college documentary project back in 2010. I fell in love with the place. Initially, it was the old-world visual appeal—things most visitors love about Mattancherry. But as I studied its history—the colonial past, the intricate weave of many communities (Malabari Jews, Goan Sonars, Anglo-Indians, Yemenis, and so many more), the spice trade, and the unique food culture—I had some context for the place apart from it being just a ‘historic place with pretty buildings’.

It was also the first time I stepped into a spice warehouse. The process of making spices involves a lot of manual labour. I still remember being embarrassed that I had no idea how all these spices made it to my table back at home. It’s a problem—this privilege, ignorance, and apathy surrounding how our food is sourced/made. So, when we did decide on Mattancherry as the setting for this story, all these instances from my time there came flooding back.

But at the end of the day, we are writing a children’s book with a word limit, so we had to pick and choose what we could include as a part of a narrative. We hope our book gives children a little peek into a place that may be unfamiliar to them. That’s our intention—to create acceptance and pique their interest.

Ala: Usually, it’s a grandma or mother who takes girls through the world of food and cooking, and there’s a gendered aspect to this. But Appoopan seems to mark a deviation from this script. Why was this the case?

Sanjana: If there is one thing we were absolutely sure about from the beginning, it was that our adult character cooking in the kitchen would be Appoopan. I grew up in a joint family of 12 people, so grocery shopping, planning the meals, prepping the ingredients, and cooking played a huge role in our daily lives. While my uncle and his sister (my mother) were in charge of the Sunday market runs, my grandfather enjoyed cooking and was very creative with his recipes. It was fascinating to see him coming up with new recipes for dinner. An hour or two later, with all of us in the kitchen cooking, we had elaborate, delicious meals. Seeing him in the kitchen made me think that this experience was quite common in every household. But when I grew up and saw the reality, I felt it was important to get kids to discover the joy of preparing a meal and sharing it with their loved ones and that your gender in no way should dictate your place in the kitchen.

Ala: Sanjana, can you tell us more about your artistic style? How did you envision the look of the illustrations? How were they influenced by the written narrative?

Sanjana: As a young art student in Chennai, I was inspired greatly by Milind Mulick—his colours and rustic themes drew me to appreciate the frames I saw around me. An art deco window, a rustic wooden lamp post, a run-down cycle, a sleeping cow all made beautiful subjects! For this particular book, Sruthi and I knew it needed a lot of panoramic views to bring out the feel of the place. We wanted each frame to look like an art print that looked interesting by itself, yet at the same time also flowed smoothly through the pages as a picture book. The architectural details, the blending of the colonial and vernacular styles, were interesting and made a great backdrop visually. In terms of colours, I wanted to bring out the typical tones of India and Mattanchery in particular. So the colour palette consisted of yellow ochres, rust red, cobalt blues.

Ala: There seem to be a good few new illustrators and authors from South India who are bringing out stories that appeal both to children and to adults. What makes them different from the books we grew up reading? Do you have any (other) favourites?

Sruthi: I loved reading Tinkle and Amar Chitra Katha growing up and I still occasionally do pick up a copy when I spot it. But in general, back then the stories we read had a standardised idea of Indianness—you could say these characters were Indian but you didn’t know much else. Let’s not even talk about books outside of India—there was absolutely no diversity or representation.

So back to Indian books, there were always these template characters—all of them looked, sounded, and dressed the same in every story. We are so diverse but our books back then were not. But now, I see so many wonderful Indian authors writing stories of inclusion and diversity. It is truly beautiful to see. I think one of the main reasons our book was picked up was because it was a story that introduces children to the Zachariah’s—a family with specific food preferences, language and practices, and it is set in a landscape that is uniquely theirs.

Our book is in no way an exhaustive account but we’ve tried our best to paint a story that is rooted in a place. Though the book is in English, we tried to make it as authentic as possible—whether we succeeded or not is for kids and parents to say.

Some of our favourite books currently: internationally, My Papi has a motorcycle by Isabel Quintero; Fry Bread: A Native American Family Story by Kevin Noble Maillard. As for Indian authors, Laxmi’s Mooch by Shelly Anand and A Sari for Ammi by Mamata Nainy.

Ala: Are the two of you working on any new exciting projects we can look out for?

Sruthi: It’s not often you share a great working partnership with a dear friend and Sanjana and I are so glad we have that. We have a ledger full of ideas at this point—we are absolutely working on a second book. The idea isn’t full-fledged yet but it is something deeply personal from both of our childhoods! We were both incredibly shy kids growing up and this is something we want to explore.

About the Creators: Sruthi is a writer and photographer from Chennai. Sanjana is an artist and a frelance illustrator. Follow them on Instagram to see more of Sruthi and Sanjana‘s work. Purchase a copy of A Little Spice Is Extra Nice here.

One comment