Islam’s relationship to images is widely discussed, often in ways that perpetuate Islamophobic stereotypes, erasing context, history, diversity, and change. Countering such popular narratives, Mohammed Sadik shows that conversations around image use in Malabar’s Muslim communities represents a long and dynamic history of debating and adapting Islamic principles to a changing world.

Mohammed Sadik. K

During my secondary education at Islahul Uloom Arabic College in 2013, I wrote an article for the class magazine reflecting on the legacy of Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez following his death. A senior artist in my class illustrated Chávez seated on a throne with the Palestine Flag and Keffiyeh for supporting independent Palestine, and armed to accompany the article. Our class teacher, an Islamic scholar, praised the artwork; however, the Arabic grammar teacher suggested that removing half of Chávez from the drawing would make it more permissible under Islamic Sharia.

Later, in 2018, during my senior secondary studies at Manhajurrashad Islamic College, a friend was awarded a statue of Lionel Messi by the college union for being the best player in the College Super League. The following morning, during the first period, our Islamic law teacher noticed the award and said to remove the possibility of Rūḥ in it. How do we understand the different reactions of my teachers to the question of imagery, and what is Ruh? In this piece, I revisit the archives of a turn-of-the-century Arabi-Malayalam newspaper to trace a history of Muslim communities’ approaches to images in Kerala.

My teachers’ interventions reflect a central principle of Islamic theology and jurisprudence—aniconism, or the avoidance of figural representation to prevent idolatry (shirk). Aniconism is applied widely in educational and religious contexts even today, and the engagement of Malabar’s Muslim community with modernity reveals a nuanced negotiation of aniconism 1.

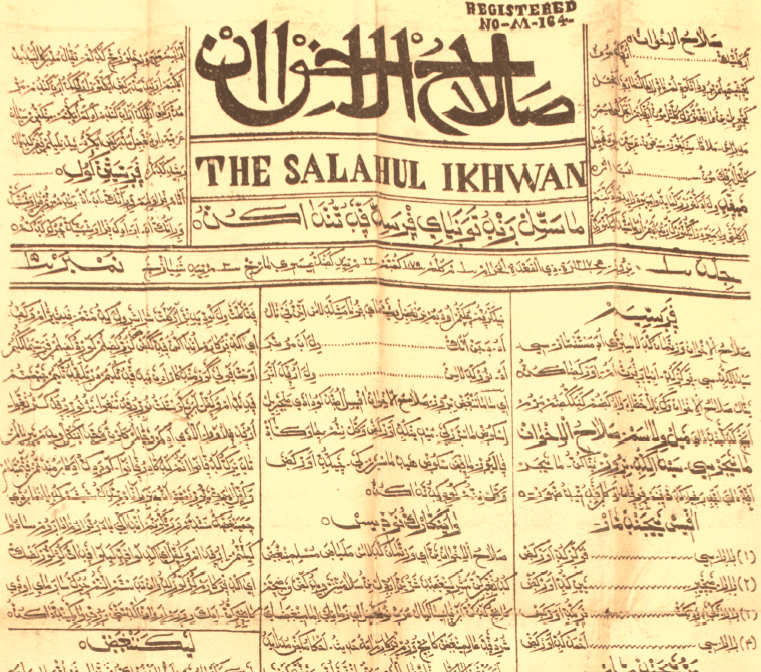

This engagement is evident in Salah-al-Ikhwan, an early Arabi-Malayalam newspaper published in Tirur, a town in the Malappuram district of Kerala, by C. Saithalikutty Master, during the late 19th and early 20th centuries (1899-1905)2. This period was significant in Kerala’s journalistic history as it marked the emergence of local-language press during the colonial era. Salah-al-Ikhwan was first printed from Ponnani, at the Mahki-al-Ghara’ib litho-press. The newspaper then moved to being printed in Tirur, at the Matba’at-al-Salahiya litho-press. Tirur, known for its rich cultural and intellectual heritage, was an important center for literary and social movements during that time. Salah-al-Ikhwan played a crucial role in disseminating information, promoting social awareness, and providing a platform for local voices during a transformative period in Kerala’s history.

While specific details about the newspaper’s exact content, editorial stance, and complete run are limited, it was likely part of the broader intellectual and social reform movements in Kerala during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The newspaper’s name, ‘Salah-al-Ikhwan’ (meaning ‘good brotherhood’), suggests an Arabic or Islamic influence, which was common in India’s multilingual and diverse cultural landscape of that time. Arabi-Malayalam, which spells out Malayalam words using Arabic script, is linguistically connected with Arabic, Persian, Tamil languages, and emerged from Malabar’s position in the Indian Ocean littoral and its centuries-long ties with the broader Islamic world through trade and cultural exchange. Its use in items like notices and newspapers like Salah-al-Ikhwan and Nisa-al-Islam3 reflects its commonality and cultural significance among the Malabar Muslim community. Newspapers of this era typically not only covered local news, but also social issues, cultural developments, and sometimes political commentary under British colonial rule. As such, apart from Malabari news, this newspaper covered news on the Ottoman empire and Caliphate, the Islamic world, and on international wars.

Images in Salah-al-Ikhwan

Advertisements for printed images on sale in Salah-al-Ikhwan offer a fascinating window into the complex cultural landscape of the region’s Muslim community. These advertisements represent more than mere commercial transactions; they are intricate cultural texts that reveal processes of identity formation, global awareness, and cultural negotiation.

At the core of these advertisements was a remarkable collection of visual representations that transcended local geographical boundaries. The images advertised for sale featured a diverse array of subjects, including Turkish Sultans, European monarchs, and significant political figures like the German Emperor and Russian Prince. The Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II emerged as a particularly significant figure, symbolizing the broader Islamic world during a period of significant political transformation—the spread of secularism, democracy, and popular media, and the British empire’s relations and conflicts with Islamic royal families like the Nizami of the Indian subcontinent and the Ottoman Caliphate.

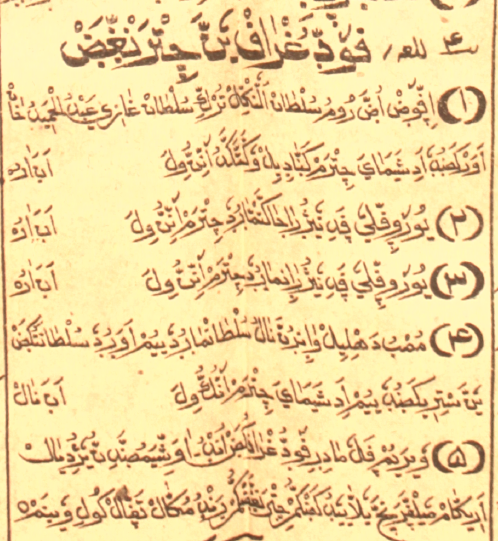

The following are two examples of advertisements that commonly appeared in the newspaper4:

Photographs5/ Images)

- The present Roman Sultan or Sultan Ghazi Abdul Hamid Khan, his wonderful picture on the mirror, costs one Anā

- The picture of seventeen kings of Europe costs six annas6

- The picture of seventeen queens of Europe costs six annas

- The wonderful picture of the women of the four sultans who ruled in Delhi and their sultanātes, costs four annas

- There are many other types of Images. If you write to me for what you need, I will send you all the above-mentioned items and pictures. Two and three quarters of the postage fee is required for each item.

Photographs7/Images

- Pictures of the Turkish Sultans, 6 annas

- Pictures of seventeen kings of Europe, 6 annas

- Pictures of seventeen queens of Europe, 6 annas

- Pictures of the English Empress, 6 annas

- Pictures of the German Emperor, 6 annas

- Pictures of the Russian Prince, 6 annas

- Pictures of an Egyptian woman, 6 annas

- Pictures of the city of London, 6 annas

- Pictures of the four sultans who ruled in Delhi and their queens, 4 annas

The pricing of these images—typically six annas for royal and political portraits—suggests a carefully constructed market that made global imagery accessible to a broad readership. This democratization of visual culture was revolutionary for its time, allowing readers to engage with distant cultural contexts and political landscapes. The selection of images reflected a nuanced engagement with colonial visual culture. The images of seventeen European kings and queens, the English Empress, and urban landscapes like London demonstrated more than mere curiosity. These visual representations mediated colonial encounters, creating alternative narratives of global connectivity. They reveal a readership actively constructing their understanding of the world beyond local boundaries. Historical imagery also played a crucial role in these advertisements—depictions of the four Delhi sultans and their queens, priced slightly lower at four annas, were particularly significant. These images served as mechanisms of cultural preservation, maintaining historical consciousness and providing a sense of continuity amid the disruptions of European colonial modernity. The advertisements also displayed a sophisticated fascination with aesthetic and exotic representations. Portraits of an Egyptian woman and scenic depictions of London highlighted an emerging cosmopolitan imagination. These images appealed to readers’ curiosity, bridging geographical and cultural distances through visual media.

The mail-order system for these images also represented a significant innovation. By making international imagery available at affordable prices in a region like Malabar, Salah-al-Ikhwan accomplished several critical interventions. These advertisements reveal the complex identity negotiations of Malabar’s Muslim community during a transformative historical period. The advertisements represent a critical site of cultural translation, where local and global, traditional and modern, intersected and negotiated meaning. These visual archives speak to an era of increasing interconnectedness. Print media from colonial Malabar tells us not only about the anti-colonial movement taking shape in the region, but also reveals the multilayered nature of cultural identity in early 20th century Malabar. Through carefully curated images, the newspaper thus created a visual bridge connecting its readers to a broader, more complex world.

The Debate on Images in Salah-al-Ikhwan

A particular discussion on image advertisements in the newspaper, prompted by a reader’s letter and the editor’s response, highlights the interplay between traditional Islamic jurisprudence, modern technology, and evolving cultural practices. The exchange provides unique insight into the community’s engagement with Sharia in a rapidly modernizing world. The reader, identifying as ‘a well-wisher of the newspaper’, wrote:

Salam to the editor of Salah-al-Ikhwan.

Dear editor, I see notices in your newspaper that images of Turkish Sultans and other kings are for sale and are being sold. If there are any Sharia rulings on whether such images are permissible to sell according to Islam and to buy and study in homes, etc., I request you to publish them in your newspaper and clarify this matter8.

This letter encapsulates the tensions between technological advancements, such as photography, and the ethical considerations dictated by Islamic law. The reader’s concern reflects the broader anxieties of the time, as Muslims grappled with integrating modern practices within the framework of their religious traditions.

In the same issue, C. Saithalikutty, the editor, provided a detailed response grounded in Islamic jurisprudence. He began by referencing Tuhfatul Muhtaj, a prominent Shafi’i legal text, to differentiate between creating physical forms and capturing reflections, the latter being akin to images seen in mirrors. He argued that images, like mirror reflections, lack physical substance and thus do not fall under the category of corporeal forms traditionally prohibited by Sharia. He cited the legal principle that a reflection does not constitute the actual physical presence of a person or object.

The editor elaborated further, stating:

“It is haram for men who have reached puberty to look at a woman they should not, but it is not haram to see her image in a mirror, as scholars have decided. Likewise, if a man declares that looking at his wife will break their talaq (divorce), seeing her reflection in a mirror does not constitute looking at her actual body.”

Using this analogy, he contended that images, like reflections, are permissible. He also acknowledged the debate among scholars regarding creating images, noting that while physical sculptures or drawings are haram or impermissible, the act of capturing images using modern technology is distinct. To further validate his position, the editor pointed to practices in other Muslim-majority regions, such as Istanbul, Egypt, and Syria, where Images were included in newspapers overseen by Sunni scholars. He asserted that such practices reinforce the permissibility of buying and selling Images when used appropriately, such as for cultural or educational purposes.

This debate demonstrates the adaptive capacity of Islamic jurisprudence when addressing new phenomena. By engaging with traditional texts and contemporary practices, the editor provided a reasoned justification for images within the bounds of Sharia law. His references to Tuhfatul Muhtaji and contemporary Arabic newspapers underscore the interplay between classical legal traditions and modern developments. The exchange in Salah-al-Ikhwan thus reflects a significant moment in the Islamic world’s encounter with modernity. It exemplifies how media platforms facilitated intellectual discourse, enabling communities to navigate the complexities of cultural and technological change while remaining rooted in their religious principles.

Images and Islam: An Ongoing Engagement

The discusison in Salah-al-Ikhwan was hardly unusual, and drew upon an existing culture of debate and interpretation. Islamic scholars have extensively discussed the permissibility and prohibition of creating and displaying images9. These discussions are deeply rooted in Islamic scripture, prophetic traditions, and legal interpretations, aiming to uphold the principles of monotheism while navigating the practical realities of art and culture. All these discussions centre the nature of Rooh (spirit) as discussed in Quranic verses and hadith, as well as prophetic traditions like those of Ibn Abbas, that address the divine nature of Rooh and the boundaries of human creative expression. These sources emphasize the serious implications of attempting to replicate divine creation. Rooh is a gift from Allah that grants life and moral accountability. While humans possess a Rooh with spiritual, moral, and intellectual dimensions, other forms of life, such as plants, are endowed with a basic life force enabling biological functions. These differences inform the permissibility of depicting various entities.

These discussions present a spectrum of scholarly positions ranging from complete prohibition to conditional permissibility, with particular attention given to the presence of Rooh (soul or life force) in depicted subjects. The core opinions include unconditional permissibility, unconditional prohibition, conditional prohibition based on the removal of vital features, and contextual permissibility as evidenced by traditions such as Aisha’s (RA) use of toys in the Prophet’s (PBUH) presence.

In addition, Islamic jurisprudence makes a clear distinction between images used decoratively or functionally and those elevated for reverence—whereas the former are permissible, as their use as carpets, pillows, or utensils inherently dishonors them, but given that the latter may lead to idolatrous practices, such image use is prohibited. This approach adds more nuance to Islamic approaches to images, and reflects the pragmatic approach of Islamic teachings, which prioritize the elimination of potential idolatrous elements while accommodating functional use10. Like the editor of Salah-al-Ikhwan, contemporary scholars have also revisited the issue in light of modern technological advancements. For example, in Kitabu Rawa’i Al-Bayan, Muhammad Ali Sawbuni argues that photographs, unlike hand-drawn images, is a mechanical process akin to looking in a mirror. As such, it does not equate to the creation of life and is generally exempt from theological objections related to Rooh11.

Art historian Finbarr Barry Flood adds another dimension to the discussion by exploring the anthropomorphism of inanimate objects. In Demolishing Myths or Mosques and Temples?, Flood argues that even representations of trees or abstract shapes can evoke questions of Rooh when given human-like features. However, he emphasizes the superiority of human and animal Rooh in terms of moral and spiritual significance, aligning with Islamic teachings that prioritize the avoidance of idolatry12.

Conclusion

This article explores the nuanced relationship between Islamic principles and cultural practices, particularly in the context of Malabar’s Muslim community. By taking up the application of a major Islamic principle—aniconism or the avoidance of figural representations—in contexts ranging from my present-day education experience to local newspapers, I show that far from being unchanging or unquestionable edicts, such principles are a matter of lively and nuanced debate and discussion, subject to revision and reinterpretation in changing times and contexts.

This study contributes to broader discussions on the circulation of imagery in the colonial and postcolonial era. While existing scholarship, such as Kajri Jain’s Gods In The Bazaar, richly examines popular Hindu-nationalist imagery, it often overlooks the vibrant engagements with imagery in Islamic and Christian communities. Similarly, school textbooks primarily highlight Ravi Varma paintings or Bharat Mata figures as emblematic of colonial- era imagery, leaving other traditions underexplored. This study adds to these conversations by foregrounding the Islamic engagements with images, demonstrating how their circulation and the accompanying debates became rich sites for creating new cosmopolitan imaginaries and engaging with modernity through the practice of Islam. The dialectical discussion with aniconism we have seen here represent not just a discussion of Islamic political theology, but open up broader questions about how people in India have engaged with modernity and tradition, and an emerging sense of the global, at a crucial point in world history.

Central to this discussion is the principle of aniconism, rooted in the Islamic emphasis on monotheism and the prohibition of idolatry. Historical practices, such as repurposing images on household items or removing the heads from statues, also demonstrate the pragmatic application of aniconism. In Malabar’s Muslim communities, this flexibility continues to allow for a nuanced engagement with modernity, where images were accepted for educational and cultural purposes without compromising religious values. From modifying representations in educational settings to incorporating global in local media, these interactions reflect a dynamic interplay between tradition and adaptation. The findings underscore the community’s ability to preserve its religious identity while embracing new mediums and cultural shifts.

Bibliography

- Al-Dimyāṭī al-Bakrī, Abū Bakr ‘Uthmān bin Muḥammad Shaṭṭā. Ḥāshiyat I‘ānat al-Ṭālibīn ‘alā Ḥall Alfāẓ Fatḥ al-Mu‘īn. Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-‘Ilmiyya, 1995.

- Al-Ghazālī, Abū Ḥāmid. Mi’yar al-‘Ilm fī al-Mantiq. Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-‘Ilmiyya, 1989.

- Al-Malībār, Zayn al-Dīn. Fatḥ al-Muʿīn bi-Sharḥ Qurrat al-ʿAyn. Beirut: Dār Ibn Ḥazm, 2004.

- Al-Qasṭallānī. Irshād al-Sārī li-Sharḥ Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī. Beirut: Dār Ibn Ḥazm, 2023.

- Al-Ṣābūnī, Muḥammad ʿAlī. Rawāʾiʿ al-Bayān Tafsīr Āyāt al-Aḥkām min al-Qurʾān. Damascus: Maktabah al-Ghazālī, 1980.

- Al-Suyūṭī, Jalāl al-Dīn. Al-Jāmiʿ al-Ṣaghīr fī Aḥādīth al-Bashīr al-Nadhīr. Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-‘Ilmiyya, 2018.

- Assaqaf, Alawi bin Muhammad. Ḥāshiyat Tarshīḥ al-Mustafīdīn ʿalā Fatḥ al-Muʿīn. Beirut: Dār al-Miʿrāj, 2023.

- Bloom, Jonathan. Arts of the City Victorious: Islamic Art and Architecture in Fatimid North Africa. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007.

- Flood, Finbarr Barry. “Between Cult and Culture: Bamiyan, Islamic Iconoclasm, and the Museum.” The Art Bulletin 84, no. 4 (2002): 641–659.

- Ibn Ḥajar al-ʿAsqalānī. Fatḥ al-Bārī. Cairo: Al-Maktabah al-Salafīyah.

- Ibn Ḥajar al-Haytamī. Tuḥfat al-Muḥtāj bi-Sharḥ al-Minhāj. Cairo: Muṣṭafā Muḥammad Press.

- Kumar, Sunil, ed. Demolishing Myths or Mosques and Temples? Readings on History and Temple Desecration in Medieval India. Gurgaon: Three Essays Collective, 2008.

- Kuwaiti Ministry of Awqaf and Islamic Affairs. Kitāb al-Mawsūʿa al-Fiqhīya al-Kuwaytīya. Kuwait: Dar al-Salasil.

- Lajnat al-Fatwā bi-l-Shabaka al-Islāmiyya. Fatāwā al-Shabaka al-Islāmiyya. Al-Maktaba al-Shāmila, 2009.

- Rabbat, Nasser. “The Meaning of the Ornament: A Gloss on the Sufi Practice.” In The Courtyard House: Between Cultural Expression and Universal Application, edited by Abeer A. Almadani, 45–47. London: Routledge, 2004.

- Ṣalāḥ al-Ikhwān. “January 22, 1901 (Hijra 1318 Shawwal 1, Kolla 1076 Makaram 10).” Maḥkī al-Gharāʾib litho-press.

- Ṣalāḥ al-Ikhwān. Volume 2, Issue 3, July 14, 1900 (Hijra 1318 Rabee’ul Awal 16, Kollam 1075 Midunam 31). Maḥkī al-Gharāʾib litho-press.

- Ṣalāḥ al-Ikhwān. Volume 3, Issue 12. Maḥkī al-Gharāʾib litho-press.

- Ṣalāḥ al-Ikhwān. Volume 5, Issue 2. Maḥkī al-Gharāʾib litho-press.

About the Author: Mohammed Sadik Kunnummal is a postgraduate student at Darul Huda Islamic University in the Department of Civilizational Studies and a writer with a keen interest in Islamic art and manuscript cultures including South Asian Muslim history. He is currently working as a sub-editor at Thelicham magazine.