Accompanied by lively illustrations of her own, anthropologist Eléonore Rimbault takes us through the ways in which Kerala’s circuses are entangled with India’s history.

Eléonore Rimbault

When I mention I came to Kerala to study the circus profession, people often have the same reaction. Why the circus? They ask. Of course, the circus is not the first thing that comes to mind when someone thinks of culture and performance in Kerala (especially considering the efforts the state has made to foreground its intangible heritage), and rarely what people in Kerala or India think worthy of being studied in their own culture. But this is arguably what makes the circus an important cultural form. Too heterogeneous and cosmopolitan to be perceived as a national staple, and yet much too local in its appeal and in the suspicions it generates to be foreign, the Indian circus, albeit its dazzling aesthetic, is also a quiet and mobile memory of India’s history over the time this traveling entertainment has existed.

The circus provides a dreamy piece of spectacle, in which the ‘items’ that the audience sees in the ring seem self-contained, suspended in the present in their intense physicality. But like anything, these feats and the form they take are historically situated, and deeply tied to the personal trajectories of the professionals who put up the show, the circus compound and its possibilities as an itinerant site, and the economy of entertainment in India. Everything in the circus is sustained through intergenerational transmission. The training of performers in circus companies forms the crux of this process of transmission, as trainees are primed to perform one or several circus items: trapeze, boneless, brick dance, shooting, juggling, ring dance…

Take the ‘tower basketball’ item (fig. 1), in which a performer slowly and painstakingly bounces a ball to the top of a pole attached to her feet—with the constant risk of having the ball quiver and fall down. A performer from Malappuram explained to me that this unusual skill, enabled and expressed by the very shape of the prop, was popularized by visits and cultural exchanges with Soviet circus performers after the 1950s. It has been developed and improved by some performers as new materials got introduced into the Indian market. For example, using pedestals of Plexiglas on the pole made it possible for the performer to dribble the ball increasingly high as they could see through the pedestals and thus aim better. The ability to use a specific ‘basketball tower’ pole has to be taught by a performer or a trainer aware of the pole’s specificities. It travels along with those who can perform the distinctive movements of this item as they get hired and work in different circus companies—the only places where this uncommon skill’s worth is known. The human and physical dimensions of the performance come together in shaping the circus; even the tents now associated with a certain circus name have changed hands many times and transformed through these handovers.

The history of the circus is an itinerant one, scattered over the subcontinent and across colonial routes linking Europe, Asia, the Persian Gulf, and Africa. But this itinerancy is decidedly not unmoored, and along Indian circus routes, the region of Malabar has had a distinctive importance. The district of Kannur, and especially Thalassery, continues to be the home place of many current owners and managers, and of past generations of artists. In the early 20th century, trainer Keeleri Kunhikannan (1858-1939), followed by some colleagues and by his own trainees, raised the first generation of Indian acrobats, trapeze artists, and gymnastic performers. 1 This training was accessible to trainees of different castes and religious upbringing, challenging local hierarchies and fostering cosmopolitan careers for pupils from poor families. Some of the trainees, specifically men from more privileged families, formed circus companies of their own, which evolved and went on to be major circuses in the 1950s.

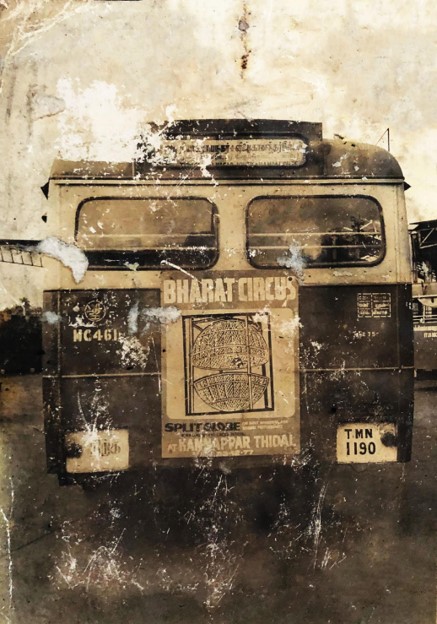

Kamala Circus (India’s sole ‘three-ring circus’), Bharat Circus, Gemini (immortalized in Raj Kapoor’s 1970 movie ‘Mera Naam Joker’), Amar, Bombay, Apollo—these and many more companies started in Malabar and constituted hiring opportunities for many young recruits in the region, so much so that to this day, retired circus artists are well-known personalities of small towns and villages across Kannur district.2

Many artists remember a time when actors, directors, and the cameras of Bollywood, Tamil, and Malayalam film industries came to the circus. These visits were not uncommon; ever since the 1940s, the circus was used as a backdrop for cinematic intrigues. Films did a lot to fixate and circulate a specific image of circus entertainment in India: Chandralekha (Gemini Studio, 1948, shot in Kamala and Great Eastern Circuses); Malayalam films as different as G. Aravindan’s Thambu (1978) and the Mammootty feature Mela (1980); Kamal Haasan’s 1989 feature Apoorva Sagodharargal. What better place to encapsulate the modernist aspirations of a society—and, very often, that society’s shortcomings—than a ring in which people are always beautiful or spectacular, animals awesome, and children virtuosic?

The glamour of the show conceals the difficulties met by circus workers in their everyday life, even to their own memory. It takes an unusual lifestyle to keep this profession alive. The circus is a place where some may not have the schooling to read and nonetheless fluently speak three languages or more. The circus tents have hosted the exchange of acrobatic and taming skills between people from all parts of the subcontinent, and celebrated marriages between Tamil and Assamese artists, and Christians and Hindus. It is a place where people with diverse backgrounds and economic means have coexisted, through thick and thin, for over 140 years.

Amidst all the difficulties that COVID-19 has brought to India, one might not immediately think of how it has affected live entertainment, let alone the circus. But due to the nature of anthropological research, it was one of the immediately obvious effects of this pandemic from my research’s vantage point. The lockdown, and all that ensued, meant that the circus workers I talked to in my work would be left with no livelihood for a prolonged period of time. Over the last year, dozens of artists have had to travel back to their native places and find alternative career paths as a ban on large gatherings curtailed the possibility of performing.

The pandemic has been the first total interruption of performances in the circus’ long history. Circus professionals have had to deal with this hardship with very little support, partly due to the stigma associated with this profession and its former use of wild animals and underage trainees, frequently portrayed as abuse in recent years. While there have been some fundraisers attempting to alleviate their difficulties, circus workers have faced unprecedented economic hardship. It is hard to know whether this form of entertainment, continuously touring India since the 1830s, will survive this new situation.

About the Author: Eléonore Rimbault is a PhD candidate in anthropology at the University of Chicago and a visual artist. Her dissertation is an ethnographic study of the practices that make the circus an enduring cultural form in India. She conducted most of her research with the Malayalam-speaking community of circus owners and performers coming from northern Kerala. Through her visual works, she explores practices of remembering and experiments with narrative forms. She can be contacted at erimbault[at]uchicago[dot]edu.

One comment