Priya Menon writes about the different dimensions of an emerging genre of ‘petrofiction’ in Keralan literature, in the context of emigration from Kerala to the Gulf countries.

Priya Menon

![]() The discovery and subsequent drilling for oil1 in the Arabian Gulf States, since the late 20th century, continue to have explicit repercussions for Kerala’s economy, polity, and society. Despite the recent decrease in migration, the Gulf States still profit from Kerala in numerous ways—around 2.2 million emigrants from Kerala form the crux of its labour force,2 not only in the hydrocarbon industry, but also by extension, in its medical, banking, transportation, hospitality, and educational facilities. The developments of these service and rentier industries have further resulted in large-scale recruitment of “guest-workers,” which reflect the magnitudes, trajectories, and potential future concerns of a primarily oil-dependent Gulf economy.3 Symbiotically, Kerala has also gained significantly from its Gulf migratory resources. Twenty-five percent of Kerala’s GDP is still based on Gulf migration.4 Therefore, it is not surprising that Gulf migration has left a significant mark on Kerala’s everyday political, physical, and vernacular landscapes. For instance, its built environment—gold markets, malls, export industrial complexes, restaurants, airports, and enormous gulf-houses,5 have all been made possible, to a large extent, by the petro-currency from the Gulf.

The discovery and subsequent drilling for oil1 in the Arabian Gulf States, since the late 20th century, continue to have explicit repercussions for Kerala’s economy, polity, and society. Despite the recent decrease in migration, the Gulf States still profit from Kerala in numerous ways—around 2.2 million emigrants from Kerala form the crux of its labour force,2 not only in the hydrocarbon industry, but also by extension, in its medical, banking, transportation, hospitality, and educational facilities. The developments of these service and rentier industries have further resulted in large-scale recruitment of “guest-workers,” which reflect the magnitudes, trajectories, and potential future concerns of a primarily oil-dependent Gulf economy.3 Symbiotically, Kerala has also gained significantly from its Gulf migratory resources. Twenty-five percent of Kerala’s GDP is still based on Gulf migration.4 Therefore, it is not surprising that Gulf migration has left a significant mark on Kerala’s everyday political, physical, and vernacular landscapes. For instance, its built environment—gold markets, malls, export industrial complexes, restaurants, airports, and enormous gulf-houses,5 have all been made possible, to a large extent, by the petro-currency from the Gulf.

Consequences of the present-day return of Gulf emigrants due to the current COVID-19 crisis along with a recent apathetic disposition for migration6 are bound to reverberate on the oil-dependent fabric of Kerala’s quotidian lived experiences. How are these experiences recorded in Kerala’s cultural archives? While the material realities of Gulf emigration get registered in diverse fields ranging from economics to sociology and policymaking, oil’s human affects remain scantily recorded and examined in Kerala. Can cultural production of narratives—especially the composition of literary fiction, that creates sites of interpretation, augment the currently dominant policy-oriented, legal, and economic discourse of this distinctive petro-cultural interaction between Gulf and Kerala? Are the (un)equal distribution of oil’s benefits and consequences imaginatively recorded in Kerala’s literary productions? What aspirational values might these texts offer through their interpretational bearings and creative possibilities for a truly sustainable Kerala Model,7 should the efficiency, attained by petroleum, become scarce or limited? What might such oil-texts mirror for Kerala’s post-oil cultural futures?

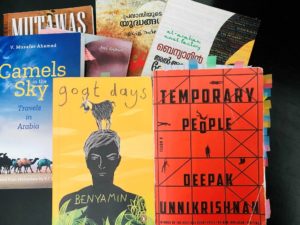

In the early 1990s, when Amitav Ghosh coined the term petrofiction in his analysis of Abdelraman Munif’s quintet of novels, Cities of Salt, to designate a literary genre that engages with the oil industry in the Arabian Gulf, he may not have anticipated its evolutionary forms in the cultural production of narratives from contemporary Kerala. While Petrofiction formerly signified fiction that directly involves any “oil-encounter” on a global scale, more recent discussions are commodious enough to include texts in which oil works “behind the scenes in very significant ways, but is never physically present.”8 If petrofiction entails a genre that is self-conscious of the fact that oil is everywhere, especially in those places where it often appears abstract, scarce, or unseen–then literary texts by Keralan writers like Benyamin, Deepak Unnikrishnan, Muzafer Ahamed, T.V. Kochubava, Methil Radhakrishnan, Shahul Valapattanam, Joy C. Raphael, Soniya Rafeek and Shihabuddin Payyuthumkadavu, to name a few, contribute to Kerala’s own evolving genre of petrofiction.

On closer scrutiny, oil’s hidden affective presence—those unique human emotive experiences represented in dance, music, and literature—is fathomable in Kerala’s cultural and literary productions as instructive aesthetic experiences for Kerala’s Gulf migratory practices. Novels such as Aadu Jeevitham by Benyamin, or lyrical performative Malayalam poetry uniquely crafted as Kattu Pattu, enacted by artists such as S.A. Jameel, and travelogues like Camels in the Sky by Muzafer Ahamed succeed in subversively documenting a unique Keralan petroculture.9 By registering oil’s complex dependencies to reveal a whole set of emotional and imaginative non-visible forms and forces of life associated with Gulf migration10—for example, a desire to persist, to make retributions and restitutions, to apologize, to resolve, to even find pleasure in migration—such literary texts offer a more generous reading of extenuating circumstances, social conditions, psychological states, and human frailties. As a result, these cultural productions from Kerala complement various existing institutional practices (such as legal, economic, or policy reforms) to restore the humanity of its emigrants.

One such text, Aadu Jeevitham—the much-acclaimed work by Benyamin, explicitly focuses on the atrocities of the inhuman but very prevalent Kafala system that exploits “guest-workers” in the Gulf by making visible human dispossession while in extremis. However, the novel also inevitably reveals how oil’s vitality tempts its protagonist, Najeeb with migration in the first place, as much as it discloses the ethical toxicity that petroleum propagates in ordinary lives of Keralans:

Meanwhile, I dreamt a host of dreams. Perhaps the same stock dreams that the 1.4 million Malayalis in the Gulf had when they were in Kerala—gold watch, fridge, TV, car, AC, tape recorder, VCP, a heavy gold chain. I shared them with Sainu as we slept together at night. ‘I don’t need anything, ikka. Do return when you have enough to secure the life of our child (son or daughter?). We don’t need to accumulate wealth like my brothers. No mansion either. A life together. That’s all. Maybe the wife of every man who is about to leave for the Gulf tells him the same thing. Even so, they end up spending twenty or thirty years of their lives there. And for what reason?11

In this light, Benyamin’s literary interpretation examines Najeeb’s distress as generating key emotional and imaginative non-visible forms of psychic aspirations during migration—the will to overcome, to survive, to reconcile, and even to find joy at times. Equally significant is the novel’s ability to depict Najeeb’s material desires (gold watch, fridge, TV, car, AC, tape recorder, VCP, a heavy gold chain) to register oil’s worldmaking12 capacities that shape his daily life and govern his choices and mobilities.13 Similarly, “In Mussafah Grew People,” Deepak Unnikrishnan conjures up a Sultan who “stinks of petrol” and orders a “Canned Malayalee Project” to “grow Malayalees on secret farms cocooned inside industrial-size greenhouse […] in twenty-three days […] to multiply its workforce by a factor of four.”14 However, fed on a formula “designed to prioritize reason,” a new batch of Malayalee workers take to “the streets near what was going to be the tallest structure in the world, and went on a strike in a country where dissent is not tolerated.”15 Here, just as the strike creates room for dissent and resistance to function as aspirational goals for Keralan emigrants, it also spectacularizes oil’s slow-violence,16 commodifying the production and consumption of workers in an apocalyptic industrial oil-farm.

Yet another text, Herbarium by Soniya Rafeek, directly addresses in a larger context, oil’s imperialism leading to environmental degradation that cuts across states, species, and scale. These texts challenge us to interpret and examine varied human—specifically the emotional and imaginative—consequences of a Keralan petroculture, while also inspiring migrant-senders and receiving state-apparatuses to initiate restitution for the costs oil-regimes extract on both human and nonhuman resources. Kerala’s petrofiction provides opportunities to craft new visions of ethical migratory practices while registering the humanity of its “guest workers” whose acknowledgement by both the oil-dependent host and home states have been distant, if not fully inimical.

Such Keralan literary texts, then, represent—perhaps not deliberately but significantly, how oil not only penetrates the geological and geopolitical but also invades the local, individual, family, and place. They allow us to interpret and live the lives and times of “others” hidden from mainstream petro-histories or are its victims. They offer the potential to alter human relationships and historical practices to make visible petroleum’s far-reaching tentacles and provide aspirational values through the empathetic act of interpretation.

About the Author: Dr Priya Menon is Associate Professor of English at Troy University, USA. She is at work on a monograph on migrant fiction from the Gulf States. Her research has been supported by a Fulbright-Nehru Excellence Fellowship, during which she was affiliated with The Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala. She can be reached at pmenon@troy.edu