In this richly layered piece, Sneha Mary Mathew explores how missionary memoirs evolved into an unintentional climate record, capturing the rhythms of monsoon, daily weather, and life in colonial Travancore.

Sneha Mary Mathew

“Nothing can surpass the perfection of climate that we have at this time of the year. The monsoon is over, and has left the earth rich ‘in all manner of store’; and, as the sun is now near the tropic of Capricorn, we have no excessive heat indoors”

Reverend Richard Collins—then Principal of CMS College—penned these words while sitting alone in his room in Kottayam, in the opening paragraph (p.1) of his book Missionary Enterprise in the East (1873). A missionary with the Church Missionary Society (CMS) in the mid-19th century, Collins originally intended the book to be a personal reflection on church work, with a particular focus on the Syrian Christians of Malabar. However, as he gathered the threads of his thoughts and wove them anew, the narrative expanded.

Missionaries often documented their perspectives rather than objective facts when writing about people, sometimes dramatizing events through their own cultural lens. However, between the lines, one can still trace valuable information such as disease outbreaks, health conditions, geographic features, and local boundaries, offering a kaleidoscopic view of the time.

In an era when weather stations existed but remained uncommon, climate knowledge lived in fishermen’s lore, farmers’ songs, and administrative ledgers. Missionaries sometimes emerged as accidental chroniclers of these patterns. Between lines of church histories and private letters lay fleeting but vital weather observations, often recorded as passing remarks rather than systematic data.

Reverend Richard Collins was different. Unlike many of his contemporaries, his observations about the climate were neither incidental nor vague. They were deliberate, sustained, and remarkably precise, transforming his religious memoir into an unintentional yet invaluable climate record.

India—in the imagination of many Europeans—was a land steeped in wonder: the home of the Vedas and the Great Mughals. Rev. Collins, reflecting the romantic perceptions of his time, described it as a place “that covers Solomon’s palace with gold and ivory, fills Athens with books, and rears the Venetian palaces” (p. 4). When he arrived in Madras on December 28, 1854, it was with the curiosity of a newcomer and an eagerness to explore—in his own words, “you try to go everywhere—or ought to do—with your eyes and your ears open.” With everything unfamiliar, he threw himself into the task of observing, reading, and learning, determined to make sense of the new world around him.

His journey took him from Madras, through the Palakkad Pass, and into the villages and towns of Travancore, where his missionary work expanded beyond religious matters. Alongside documenting church life, he recorded local customs, music, architecture, and oral legends. More significantly, he took note of the changing weather patterns around him.

While to the east from May to September the Carnatic is parched up with hot land winds, on the west the black clouds of the south-west monsoon are gathering over the Ghauts, and pouring their floods of water on the jungles of Malabar; and while from September to January the north-west monsoon is deluging the Carnatic, the west is beginning to glow under cloudless skies. (p.5)

In passages like these, Missionary Enterprise in the East becomes more than a religious memoir. It emerges as a historical document—a record of monsoon, climatic events, and the usual and unusual weather events as it existed in mid-19th-century Travancore.

Like a ritual: Collins’ Meteorological Notes

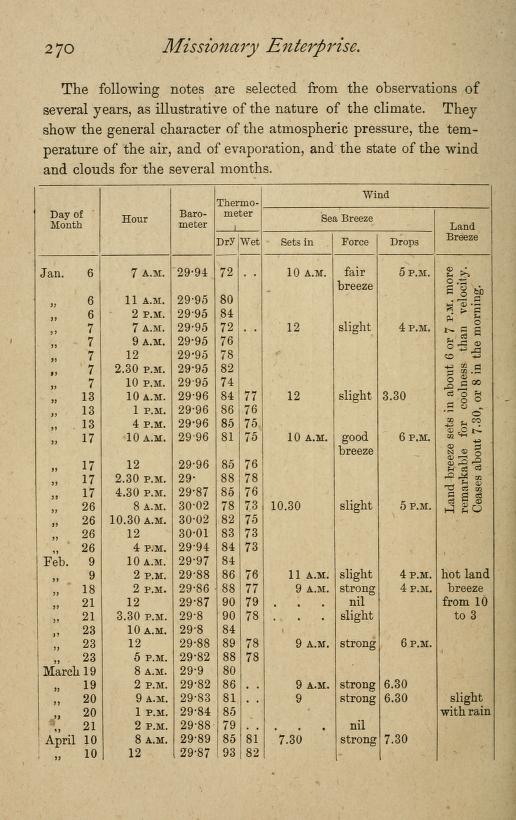

From November to May we have on the Western coast a steady sea breeze during the day, in which the thermometer seldom rises above 84° or 85° in the shade; and at night we have a gentler land breeze, which lasts till a few hours after sunrise. During the sea breeze I have repeatedly noticed an upper current of air from east to west — that is, exactly opposite in direction to the sea breeze. This upper current I believe to be permanent at that time of the year. (p. 21)

This was not a casual note or a passing remark. Neither was it merely a recording of a single thermometer reading nor a broad description of well-known climatic patterns. Rather, it was a reflection of Collins’ systematic and dedicated approach to meteorological observation. The appendix titled “Rainfall at Cottayam and Meteorological Notes” reflects his commitment to recording, observing, and understanding the climate as a carefully planned scientific pursuit.

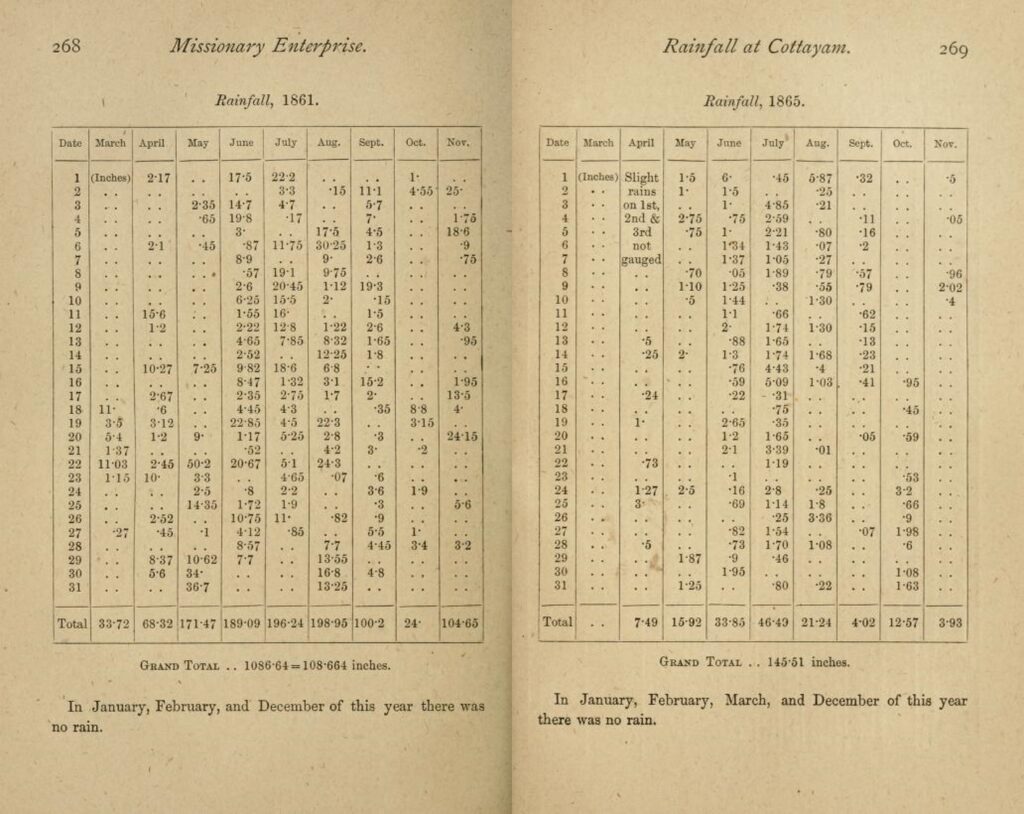

Daily rainfall records for the years 1861 and 1865 were diligently kept by Collins, with detailed entries for each day across the months. “December, January, and February are usually without rain,” he noted — a statement supported by his rainfall data.

Interestingly, this aligns with broader data from the Travancore Almanac of 1878, which published the meteorological observations conducted by John Allan Brown at the Travancore Observatory between 1859 and 1864. These records also confirm that December 1861 was rainless. Also, for five years (1840, 1854, 1856, 1860, and 1864), the month of January recorded no rain. According to Collins, January 1861 was also rainless. These variations might reflect the regional differences in rainfall patterns between Trivandrum, where Brown was based, and Kottayam, where Collins conducted his observations.

Travancore State Manual Vol 1., noted “The Kottayam Division receives three times as much rain as the Padmanabhapuram Division.” (p.66) Rev. Collins’ own notes echo this, stating: “The average rainfall of Cottayam is very much greater than at Trivandrum.”(p. 267)

More than the numbers, there lies a richness of observation in Collins’s records. Take, for instance, the land breeze—that gentle wind drifting from land to sea during the night or early morning. He wrote it down whenever he felt it, sometimes noting the exact hour, at other times simply describing how it made him feel. This wasn’t the work of a single year, but a quiet ritual, practised with care and consistency. Over time, he came to understand its changing nature — cooler in the early hours of January, gentle and rain-laced in March and April, or entirely absent during the heavy monsoon months of June to September. And the monsoons? Again, they were not merely remembered, but recorded:

- May 22, 1861 – Monsoon fully sets in

- June 15, 1864 – Monsoon set in June 1st precisely

- June 1, 1865 – Monsoon set in

“Repeatedly noticed,” “frequently seen”—Collins chose his words carefully. These were not one-time phenomena, but patterns, etched into the rhythm of the land. He described them to his readers with quiet confidence, as if to say: this is real, this is true, and you must see it as I do.

Missionaries as Witnesses to Environmental History

While Reverend Collins’ meteorological notes reflected a deliberate, academic approach to climate observation, other missionary records emerged in different ways. Many missionaries recorded their experiences not with instruments or measurements, but as third-party witnesses to events where climate and human life became inextricably intertwined. In moments of disaster, those addressing the spiritual needs of the people also found themselves compelled to address their suffering. In doing so, they became witnesses to the climate’s consequences.

“As for periods of deficient rainfall, it is on record that the year 1860 was a year of famine in South Travancore” (p.66). The Travancore State Manual, Vol. 1, briefly notes the famine of 1860 thus. But what did it truly mean for the people who lived through it? What were the consequences?

A more vivid and devastating picture emerges from other sources:

In 1860 South Travancore was visited by a severe famine. The monsoon failed, the stock of food grains was soon exhausted, and the people died in great numbers from starvation, many bodies being left by the roadside. The famine brought disease in its train, and dysentery and cholera reaped a second harvest of victims.(p. 51)

Rev. I. H. Hacker, a missionary of the London Missionary Society, wrote about this famine in A Hundred Years in Travancore. In his endeavour to document the mission’s efforts, he left behind a striking historical record of the famine and its aftermath, noting that relief efforts were mobilized swiftly, supported by generous donations from abroad. In the same book, he records the words of the then Dewan Madhava Rao, who expressed his gratitude: “Can there be a nobler spectacle than that of a people thousands of miles removed from India contributing so liberally to the relief of suffering here?” (p. 52)

“On Sunday the 23rd ultimo (November) we were visited at about 2 o’clock P.M. by a slight shock of earthquake, succeeded by a rumbling noise resembling that of distant thunder”, wrote Rev. Benjamin Bailey in a letter to General Cullen (p.73). This recollection of the 1845 earthquake was later recorded in the Travancore State Manual Vol 1, lending official recognition to what began as a personal account.

Conclusion

From the coasts of South India to the interiors of Africa and the ports of eastern China, the missionaries recorded more than faith. They wrote of dried-up wells and waterless springs at mission houses, like those documented in the Otjimbingwe station chronicle in Namibia, 1901. They wrote of sickness and death—of a “remarkably sickly and fatal” month in Shanghai, where, as one letter noted, more funerals had taken place than ever before. Others wrote of violent rainfalls, blazing sun, endless drought and harsh realisations- “Nature in this country treats these poor people more than uncharitably”.

The records left behind were more than mere documentation—not just of suffering, but of happenings. Their letters, memoirs, reports, and books—meant to chronicle the spread of the gospel—also offer a textured archive of daily life, cultural encounters, landscapes, wildlife, and weather. Often unintentionally, they serve as witnesses to climate events. Whether through the scientific precision of Rev. Collins or the heartfelt reports of Rev. Hacker, these writings offer invaluable historical evidence. In their quiet way, they preserve the story of how the climate shaped lives—and how lives, in turn, bore witness to the changing skies.

References

- Collins, Rev. Richard. Missionary Enterprise in the East. CMS College, Kottayam, 1873.

- Hacker, Rev. Isaac Henry. A Hundred Years in Travancore, 1806–1906: A History and Description of the Work Done by the London Missionary Society in Travancore, South India, During the Past Century. London Missionary Society, 1908.

- Nagam Aiya, V. The Travancore State Manual, Vol. I. Government Press, 1906.

- Travancore Almanac for 1878.

About the Author: Sneha Mary Mathew is a Research Scholar at BSIP, Lucknow.