Tracing how sound cultures and sonic media technologies—from gramophones to audio cassettes—shaped Kerala’s film culture in the twentieth century, Alex Abraham explores how informal infrastructures enabled new listening practices, expanded cinema beyond the theatre, and influenced the rise of genres like mimicry and comedy in Malayalam cinema.

Alex Abraham

Kerala has a rich history of sound cultures history of sound cultures,1 with the consumption and circulation of regional media forms through different sonic media technologies. This article pays attention to the developments in the twentieth century to understand the role of sonic media technologies and sound cultures associated with them in the film culture of Kerala. To analyse this, I use the concept of media infrastructures. Media infrastructures are “the material sites and objects involved in the local, national, and/or global distribution of audiovisual signals and data” (Parks, 2015). As Brian Larkin (2008) suggests, the media infrastructures determine the circulation of media forms and shape the ways of cultural flows and consumption. Using this framework in the context of Kerala, I argue that a sonic media infrastructure, which consists of the media technologies and broader material sites, networks, and contexts formed in Kerala during the twentieth century. Further, I explore how the sonic media infrastructure shaped the experience and engagement with cinema beyond the space of cinema halls through sound culture and listening practices. For this, the article draws from archival materials, oral histories, and autobiographical memoirs of radio professionals.

The formation of a sonic media infrastructure in Kerala

A music boom happened in the Tamil-speaking parts of the Madras Presidency during the 1920s and 1930s with the arrival of gramophone and vernacular records. Gramophone companies created a vernacular market in South India by the 1910s (Hughes, 2002). This music boom also created ripples in the Malayalam-speaking parts of the Madras Presidency. During the archival research, the oldest gramophone record identified as Malayalam that I could find is from 1911. In 1911, His Masters Voice (HMV) released Chidhambara Darashanam, Giri Thaniye, Sakhiye Anasooye, and Dulare as Malayalam records sung by T.C Narayani Ammal (Figure 1). Even though the records were catalogued as Malayalam, they had more affinity for Carnatic music. This was a strategy of the gramophone companies since Carnatic music appealed to most of the upper-class consumers of gramophones across the linguistic regions in South India (Hughes, 2002). From the 1920s onwards, the number of Malayalam records started to increase. The Gramophone, however, remained restricted in its access. Only the elite classes could afford the gramophone in private spaces, especially in the early period. Nevertheless, the gramophone contributed to the sound culture of Kerala through its presence in public spaces such as cinema halls, schools, toddy shops and so on.2

Even though the gramophone sustained listening practices and contributed to the circulation of a variety of sonic media forms, it was the radio that extended the scope of the listening practices. All India Radio started a radio station in Kozhikode in 1950. However, the first radio station in Kerala was in the princely state of Travancore, known as “Travancore State Broadcasting”, which started in 1943 and was taken over by All India Radio in 1950 (Nair, 1983). The Travancore State Broadcasting covered only a minimal geographical area. From the 1940s onwards, Malayalam programs were broadcast from Madras AIR station, but it did not necessarily create a wider radio audience in the region of Kerala. Even in Madras city, during the early period radio reached the masses through public listening practices (Hughes, 2002; Nair, 1983). Similar modes of public listening were present in the Malabar region as well. K. Padmanabhan Nair, who started working in AIR Madras in 1945 and was appointed as program officer when AIR Kozhikode started in 1950, in his memoir, mentions radios installed in public parks such as Ansari Park in Kozhikode during the late 1940s (Nair, 1983).

The radio broadcasting expanded in Kerala during the 1950s with AIR stations in Trivandrum and Kozhikode, but still with less coverage and access. K. Padmanabhan Nair’s memoir shows that radio remained a rare domestic media. According to him, during this period, most people accessed radio in spaces such as restaurants, barbershops, and tea stalls. Radio broadcasting in Kerala further expanded with stations beginning in Thrissur and Alappuzha, which started in 1956 and 1976, respectively. With radio being more accessible by the 1970s the technologically mediated listening cultures in Kerala grew.

A significant transformation in the sound cultures in Kerala happened with the arrival of audio cassettes. While the gramophone was limited in its circulation and accessibility, and the radio functioned under the control of the state, the audio cassettes were both accessible and functioned beyond the strict control of the state. Furthermore, the materiality of audio cassettes made them easy to reproduce, leading to the emergence of pirate media infrastructure through which it circulated at lower prices and reached the masses.3 Tape recorders and audio cassettes entered Kerala through the infrastructures enabled by Gulf migration. Their circulation was supported by infrastructures such as informal trade networks and markets, audio cassette shops and piracy. The Gulf boom in Kerala has contributed to the emergence of different informal trade practices, giving rise to Gulf markets. Practices of buying Gulf goods, which included clothes, toys, processed food items, and electronic goods, from returning Gulf migrants for selling were prevalent throughout the period.4 Hence, the tape recorders and, initially, audio cassettes circulated in Kerala as part of the emerging material culture associated with Gulf migration.

The media technologies from gramophone to audio cassettes and the associated infrastructures that enabled their circulation and consumption, such as the informal trade networks, the policies of the state, piracy, cassette shops, media practices such as collective listening and so on, created material sites and practices that enabled the circulation of sonic media forms in Kerala. Together, these sites, technologies and practices created the sonic media infrastructure. Here, I am drawing from the understanding of media infrastructure as material resources arranged for the circulation of audio-visual data (Parks, 2015). Brian Larkin (2008) observes that social contexts shape media technologies and media infrastructures, and they are often put into unintended uses, thus creating new possibilities. The sonic media infrastructure sustained specific sound and listening cultures in Kerala. They have shaped and created new possibilities to engage with music, religion, politics, nation, and cinema.

Sonic forms of cinema in circulation through sonic media infrastructure

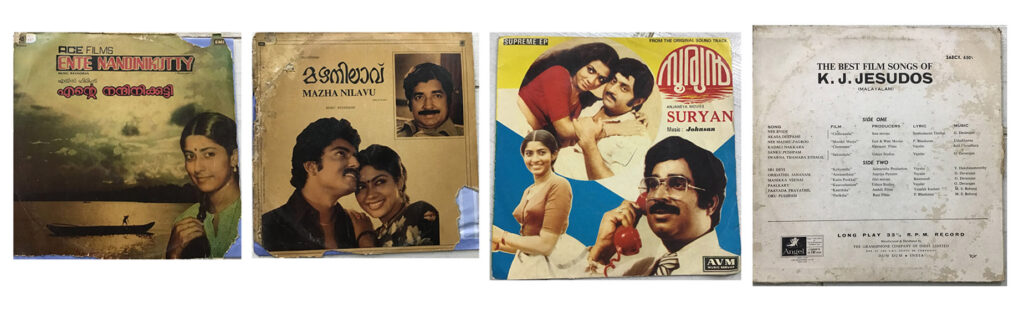

The gramophone, especially in its early period, circulated comic sketches, Christian devotional songs, Mappila songs, Carnatic music, and instrumental music in Kerala. From the catalogues of gramophone labels such as HMV, we can see the Malayalam gramophone genres circulating in the 1930s with dedicated Malayalam gramophone artists such as Miss Rosa Ernakulam, Miss Sara Bai, Master K. Gul Muhomed, Mr. S. R Iyer, and Blind Singer Parikutty Moplah.5 Film music became an important media form circulating through gramophone records in Kerala with the advent of sound cinema and the increasing production of Malayalam cinema after the 1950s. Shortly, vinyl records entered the market and film music started to circulate in more numbers through them. The vinyl records had the advantage of more playback time compared to shellac-based gramophone records and, hence, could accommodate more songs. But both shellac-based gramophone records and vinyl records had a limited consumer base.6

The circulation of film music continued through radio and audio cassettes. Film songs became one of the key elements in the soundscape of Kerala, especially with the popularity and accessibility of audio cassettes, which, starting from the 1970s, were available easily and cheaply due to the practice of media piracy and the networks it enabled. More compact models of tape recorders came by the 1990s, and the listening practices associated with audio cassettes expanded.7 Audio cassette shops also grew in numbers, with cassettes available even from street vendors. Film songs became part of everyday life, playing and making a material presence in multiple spaces, from restaurants to public and private transport. This continued with the further advancement of media technologies and with the arrival of MP3 players.8

The circulation of film songs through the sonic media infrastructure is an obvious observation of its role in Kerala’s film culture. I want to emphasise two different media forms, Chalachithra Shabdharekha and the compilation cassettes, which compiled comic dialogues from various films, often categorised according to actors. Shabdharekaha is the full soundtrack of cinema, often reshaped to suit the materiality of sonic media, which started to be broadcast through AIR in Kerala from the 1970s onwards. During this period, radio broadcasting started gaining prominence in Kerala, and the production of Malayalam cinema was steadily rising. There were only five Malayalam films produced between 1929 to 1947. However, between 1955 and 1968, 225 Malayalam films were produced (Venkiteswaran, 2011). Radio could not stay away from the flourishing Malayalam film culture. In this context, Shabdharekha and regular Malayalam film music programmes started from the 1970s onwards (Nair, 1983).

Shabdharekha provided new affordances for film consumption. With radio becoming a ubiquitous domestic media technology by the 1970s and 1980s, it can be considered one of the first instances of domestic film consumption in Kerala. The memoirs of K Padmanabhan Nair show that Shabdharekha and film music programs were very popular, with even film festivals being conducted through radio featuring Shabdharekha. With the growing popularity of audio cassettes, the Shabdharekha also circulated through them (Figure 3). Another important sonic form of cinema circulated through audio cassettes was the compilation of comedy scenes. The compilation of comedy dialogues by all the prominent comic actors was circulated widely through audio cassettes. They played a crucial role in maintaining the presence of cinema beyond cinema halls and especially in the domestic space.

What we are observing is cinema adapting the materiality of the sonic media infrastructure and being reshaped for circulation through it. With this development, cinema became an essential part of the listening cultures surrounding Kerala’s sonic media infrastructure. In the words of Brian Larkin (2008), media have material and sensual qualities, and they “stimulate new aesthetic forms that borrow from older ones, adapting and reworking them, creating new forms from old” (5). The sonic media technologies and infrastructures similarly borrowed from the existing form of cinema and reworked it to suit the material qualities of sonic media infrastructure.

The contributions of the sonic media infrastructure to film culture in Kerala were not just the circulation of sonic forms of cinema but also its role in the emergence and popularity of the comedy genre in the 1990s. By the 1980s, mimicry, an art form that predominantly involve imitating different sounds such as sounds found in nature, everyday life, and sounds of film stars and politicians, emerged as an established public art form in Kerala (Sebastian, 2022). Since mimicry was predominantly a sound-based performance, the mimicry artists and troupes suddenly embraced audio cassettes. During the 1980s and 1990s, there was a flood of mimicry cassettes. The audio cassettes helped the art form of mimicry to reach the masses. Mimicry artists became popular and started to enter the cinema. Malayalam cinema was impacted by mimicry and its popularity, not just in the entry of new actors, writers, and directors but also in theme and form. In this way, the sonic media infrastructure played a crucial role in the emergence of the trend of laughter films in Malayalam starting from the late 1980s onwards and in the creation of new film stars in Malayalam cinema. The ripples of mimicry can be observed even today, from television and cinema to new media forms circulating through social media.

Conclusion

The article’s intention was to look into the role of sound culture in the film culture in Kerala. Cinema is often not understood in relation to the sound cultures it is part of, mostly because of the dominance of visuals in the medium. However, cinema is an important part of sound cultures and is, in turn, shaped by them. As discussed, cinema in various sonic forms is circulated and consumed through the sonic media infrastructure in Kerala. This infrastructure is formed as part of a complex social and cultural process. Further historical and ethnographic studies could provide deeper insight into sound cultures and their role in the film culture of Kerala. The sound culture of Kerala remains underexplored, even though sound cultures and listening practices are crucial in our cultural landscape.

References

- Hughes, S. P. (2002). The “Music Boom” in Tamil South India: Gramophone, radio and the making of mass culture. Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, 22(4), 445–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/0143968022000012129

- Larkin, B. (2008). Signal and Noise: Media, Infrastructure, and Urban Culture in Nigeria. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822389316

- Nair, K. P. (1983). Radiotharangam. Sahitya Pravarthaka Co-Operative Society Ltd. .

- Parks, L. (2015). “Stuff You Can Kick”: Toward a Theory of Media Infrastructures. In P. Svensson & D. T. Goldberg (Eds.), Between Humanities and the Digital (pp. 355–374). The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9465.003.0031

- Sebastian, T. (2022). Laughter and abjection: The politics of comedy in Malayalam cinema. In P. Kumar (Ed.), Sexuality, Abjection and Queer Existence in Contemporary India (pp. 112–130). Routledge.

- Venkiteswaran, C. S. (2011). Malayala Cinema Padanangal. DC Books.

About: Alex Abraham is a research scholar in the Department of Film Studies at the English and Foreign Languages University, Hyderabad. His areas of interest include the history of media technologies, film history, and the informal media economy. He is currently researching the intersection of media infrastructures and film consumption practices in Kerala.