What does it mean to “mother” from another country? Aleena brings to our attention the ways in which migrant women’s self-narratives throw light on their relationships with their children, family, and home.

Aleena Felix

ആത്മാവിൽ തിങ്ങുന്ന വേദനയുമായ്

ഇനിയും എത്രനാൾ തുടരണമീ ജീവിതയാത്ര

നാടില്ല, വീടില്ല, മക്കളുമില്ല കൂടെ

ജീവിതത്തോണി തുഴയുന്നു ഞാനേകയായി

With a suffocating pain in my soul,

For how long will I continue this life’s journey,

No land, no home, away from my children

Alone, I row this lonely boat that is my life.

Ancy Mathew “ജീവിതയാത്ര” (My Life’s Journey), 2009 (My translation)

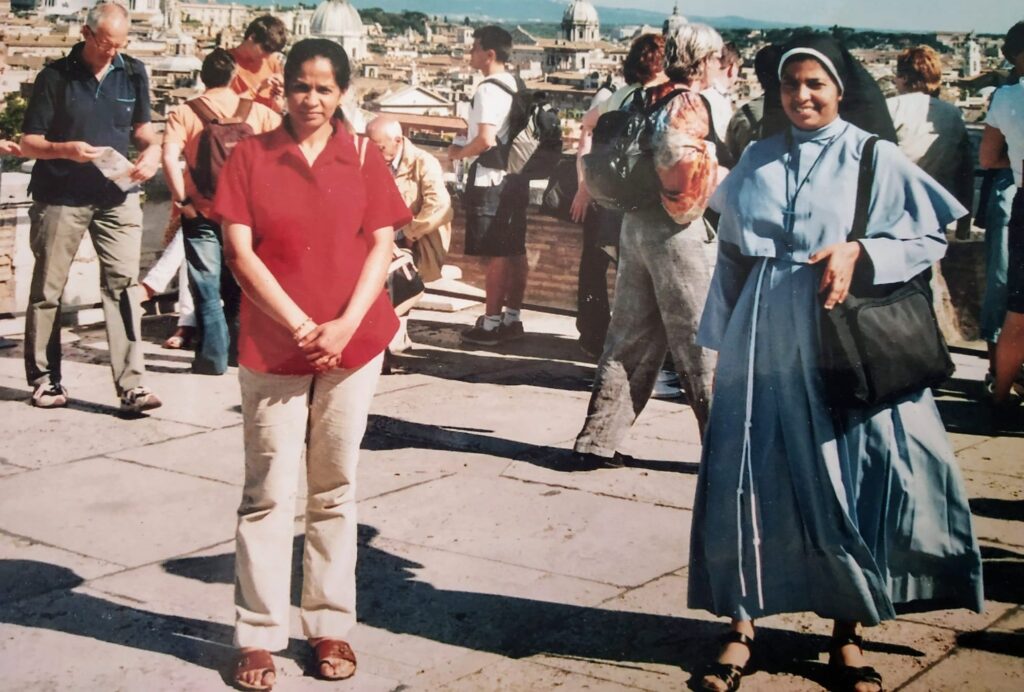

My friend often used to tell us a story about her mother’s migration to Italy for work. With her flair for storytelling, she told us that her mother, Ancy, left home one day to buy groceries only to come back five years later from Italy with lots of chocolates and Nutella!! Such stories are common among children whose parents, especially mothers, are away from them. Ancy couldn’t tell her daughter that she was moving away for work, nor could she know what her future would look like as an undocumented migrant to a foreign country. Unprecedented times were ahead of her, away from her homeland, children, and loved ones. The decision to go and the courage to stick to it were all that was certain.

The migration of women from Kerala to European countries began as early as the 1960s (Osella and Osella 2000, Gallo 2008, George 2005, Goel 2024).1 Even then, popular narratives revolve around migrations to the Gulf, mostly by men from different parts2 of the state. These studies particularly focus on the socioeconomic patterns that emerge out of such transcontinental movements. Despite their participation as healthcare workers, domestic labourers, and homemakers, women are not sufficiently recognised for their lived experiences as migrants who have been economically and culturally contributing to the family, society and state.3 Their narratives seldom cross the boundaries of the household.

When it comes to thinking together about the gendered experience of migration by women, we have often turned to cinema. It has been a cultural repertoire for the varied Malayali migration experience with films that portray its economic, political, and gendered experiences. Malayalam mainstream films have dealt with the figure of the migrant woman in films such as Khaddama (2011) and Take Off (2017). But they largely present realities of undocumented migration or the oppression faced by migrant women in the host country. Films like Life of Josutty (2015), Kadal Kadanny Oru Mathukutty (2013) are films that represent the life of migrants in Europe. But they have resorted to the narrative of migrant women as cheating wives or arrogant daughters. The meanings these movies produce and the impact they have often end up isolating women’s experiences.

Without diminishing the relevance of these representations to make the public collectively think about what migration entails, I want to draw attention to self-narratives that weave together the imprints of the family and home that women carry with them as they move far away. The negotiations that migrant women, especially mothers, make with the home and the foreign country constitute their lived experience of migration and play a formative role in how they think about themselves. The home and what they have left behind continue to play a crucial role in determining their experiences in the new country. However, these rarely figure in academic and popular representations of migration from Kerala. Let’s turn our gaze to the story that my article started with–Ancy’s experience of having to leave her children in complete darkness about the reasons for their mother’s prolonged absence does not fare in these works. But these stories ooze out through oral narratives, letters, and phone conversations. Engaging with them–both the stories and the storytellers–is important, lest we, as Mohamed Shafeeq writes, forget what migration really means.

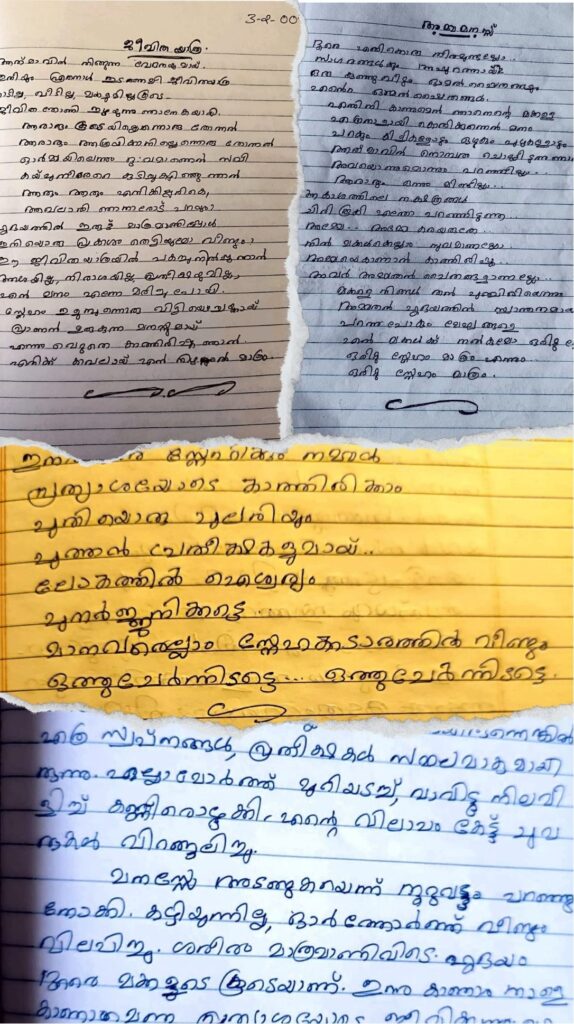

Ancy bore a “suffocating pain” as a mother forced to be away from her children. Writing poems gave her a way to express and translate that pain into words. As she handed over a bundle of her writings (whatever had survived her years abroad) to me, she wanted them to be read and her past to be heard.4 Migrant women bear stories shaped by their gendered experience of migration. As this mother’s narrative shows, they juggle emotions, forms of resilience, and survival strategies. Looking into their writings and narratives offers a glimpse into how they situate their belongingness in times of unfamiliarity and loneliness. The ways in which they narrate themselves and determine how they want to be heard are political acts waged against conditions that govern their lives. Ancy’s diary entries5 map her arrival as an undocumented migrant in Italy from Kerala in 2006–a journey she undertook with her friend, holding a language guidebook in her hand.

Where is the mother? Can she mother from across the borders?

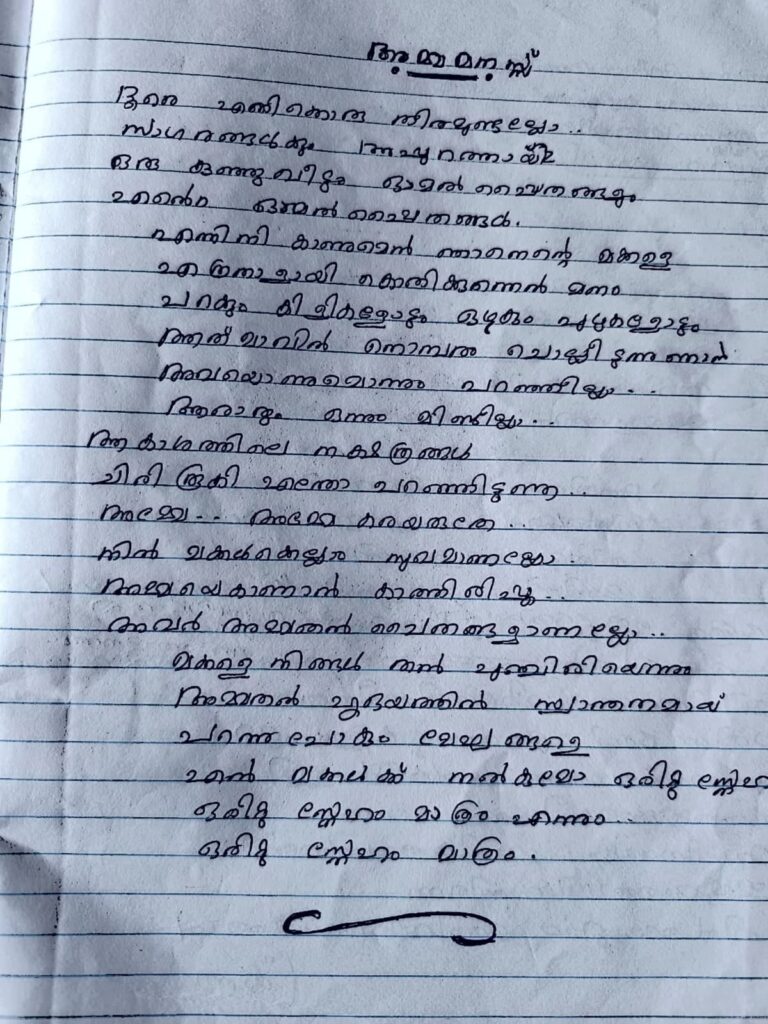

In Ancy’s writing, what I found most striking is her engagement with her role as a mother across borders. She reflects on what she feels to be in a state of separation from her family and children. In the poem “അമ്മമനസ്സ്” (The Mother’s Mind), Ancy writes:

മക്കളെ നിങ്ങൾതൻ പുഞ്ചിരിയെന്നും

അമ്മതൻ ഹൃദയത്തിൽ സാന്ത്വനമായ്

പറന്നുപോകും മേഘങ്ങളെ

എൻ മക്കൾക്ക് നൽകാമോ ഒരിറ്റു സ്നേഹം

ഒരിറ്റു സ്നേഹം മാത്രം

എന്നും ഒരിറ്റു സ്നേഹം മാത്രം. (lines 17-22)

She asks the clouds to send messages to her children as she is unable to go back home despite her wishes. She asks the passing cloud, which can easily move across borders, to convey her messages and show affection to her children. The elements of nature do not need to acknowledge national borders and are symbols of freedom while she is caught in the legalities of the visa application that immobilise her even when her dear ones are suffering.

Her narratives seek to explain her situation and her choices through the emphasis she gives her pain and her love for her family and homeland. Her echoing questions show us the ways in which women are intricately tied to the household and its kinship relations in ways that men are not. The management of the household and the hours of unpaid, and mostly unacknowledged, labour and care work that goes into it determine their value. This, in most cases, is in addition to their “recognised” economic contribution. This complex value system is frequently oversimplified by social and cultural norms, so much so that women who migrate, for whatever reasons, suffer the blame for leaving their families behind. This is often the case even in Kerala, when as we noted earlier, the culture of migration is very much prevalent across genders. Women who migrate carry with them this criticism of being failed wives and mothers, even when those very families need/force them to earn a decent living for all of them by moving abroad. The ways in which they thought about themselves and such criticisms raised against them are revealed in their narratives.

The migrant women/mothers that I interviewed frequently asserted their sense of self as women who followed their “culture”. Their emphasis on this aspect particularly speaks to a society that views women who migrate from home with suspicion.6 In Ancy’s poem, we can see her addressing these cultural norms. frequently emphasising her sacrifices for her family, her loneliness, and her memories of those she has left behind.

വർണ്ണങ്ങളും സ്വപ്നങ്ങളുമകലെ

ചുറ്റും തിങ്ങും ഇരുട്ട് മാത്രം

പ്രഭാതത്തിൽ വിരിയുന്ന

വെള്ളാമ്പൽപൂവ് പോലെ

നാളെയെന്ന സ്വപ്നം

നെഞ്ചിൽ കൂട് കൂട്ടി

കൂട്ടിനുള്ളിൽ വിരുന്നിനെത്തി

എൻ കിളിക്കുഞ്ഞുങ്ങൾ

Colours and shades fade away.

A darkness engulfs me.

Like a water lily that blooms in the morning,

A dream of another day

Built its nest in my heart

And inside that my little birds came calling

(Mathew, lines 7-14, Diary, 09 March 2009, My translation)

Thoughts about the home constitute her life abroad. They layer her sadness and loneliness, which she represses with her dreamy imagination of meeting her children after each passing day. Scattered across her diary entries, as this excerpt shows, are instances of hope, moments of losing it, and the desperate need to survive. Memories of her children keep coming up, holding together the need to survive and fight through the loneliness. Despite her efforts, we see instances in her writing where this willpower collapses:

എനിക്ക് ചിറകുകൾ ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നെങ്കിൽ എന്നേ എൻ്റെ മക്കളുടെ അടുത്ത് ഞാൻ എത്തുമായിരുന്നു. അവർക്ക് ചിറകുകൾ ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നെങ്കിൽ എൻ്റെയടുക്കൽ അവരും എത്തുമായിരുന്നു. നമ്മുടെ ആഗ്രഹങ്ങൾപോലെ എല്ലാം നടക്കുമായിരുന്നെങ്കിൽ എത്ര സ്വപ്നങ്ങൾ, പ്രതീക്ഷകൾ സഫലമാകുമായിരുന്നു. എല്ലാമോർത്ത് മുറിയടച്ച്, വാവിട്ടു നിലവിളിച്ച് കണ്ണീരൊഴുക്കി. എൻ്റെ വിലാപം കേട്ട് ചുവരുകൾ വിറങ്ങലിച്ചു.

She longs for wings for herself and her children so they could reunite, but as she dwells on this dream, she confronts the harsh clash between her desires and reality. She sighs, wondering how many hopes and dreams would have flourished if wishes alone could make them come true. Remembering everything, within closed doors, I wailed; hearing me mourn, the walls shivered.)

(Mathew, Diary, 07 July 2010; my translation)

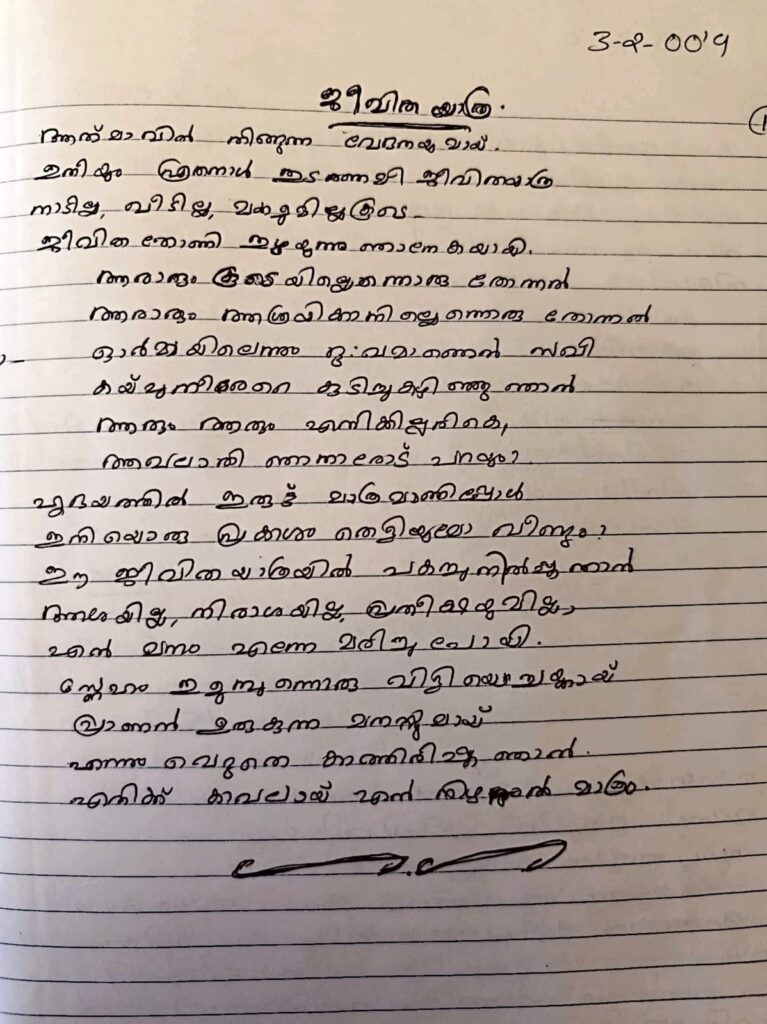

In the poem titled, ജീവിതയാത്ര (Life’s Journey), she writes;

ആരാരും കൂടെയില്ലന്നൊരു തോന്നൽ

ആരാരും ആശ്രയമില്ലന്നൊരു തോന്നൽ

ഓർമ്മയിലെന്നും ദുഃഖമാണെൻ സഖി

കയ്പുനീരേറെ കുടിച്ചു കഴിഞ്ഞു ഞാൻ

ആരാരും എനിക്കില്ലരികെ

ആവലാതി ഞാനരോട് പറയും?

A feeling that there is no one with me

A feeling that there is no one to rely on

In all my memories, sadness is my partner

May a bitter juices have I drank

Nobody, nobody, is there with me

Who will I share my agonies with?

(Mathew, Diary, 02 February, 2009; My translation.)

In her piece, പ്രവാസി അമ്മ (The Expatriate Mother), she writes:

ഏതുനാട്ടിൽ ജീവിച്ചാലും സ്വന്തം സംസ്കാരവും വിശ്വാസവും മുറുകെപ്പിടിച്ച്, മറ്റുള്ളവർക്ക് മാതൃകയാകണം എന്ന് ചിന്തിച്ചു ജീവിക്കുന്നവരാണവർ. എന്നിട്ടും പണത്തിനുവേണ്ടി മാത്രം കൈ നീട്ടുന്നവരുമുണ്ട് . സ്വന്തം കുഞ്ഞുങ്ങൾക്കും താനൊരു പ്രവാസിയാണല്ലോ , അവരുടെ സ്നേഹം തനിക്ക് നഷ്ടമായാലോ എന്നോർത്തു വിലപിക്കുന്ന ചില നിമിഷങ്ങളുമുണ്ട്. ആ അമ്മ ഉരുകിത്തീരുന്നത് എന്തിനവേണ്ടിയാണ്? മറ്റുള്ളവരുടെ ജീവിതത്തിൽ തിരി തെളിയിക്കാനാണ്. (Mathew, Diary, 16-05-2018)

She writes about the values a migrant mother upholds in her life and the morality that she derives from her culture and religion. She desires to be a living example, but is often seen only for their ability to earn money. Despite her sacrifices, she grieves that she is a migrant for her children. These thoughts feel heavier when she is unseen and unheard. It gets clearer in the following paragraph, where she wonders if her children will ever understand her pain. This is reflected in her writings.

ശരീരം മാത്രമാണിവിടെ.

ഹൃദയം ദൂരെ മക്കളുടെ കൂടെയാണ്.

ഇന്ന് കാണാം നാളെ കാണാമെന്ന പ്രത്യാശയോടെ ജീവിക്കുന്നു.

മക്കളുടെ ഹൃദയം നൊന്തിടുമ്പോൾ

മാതൃഹൃദയം അറിയുന്നു . അവർക്കുവേണ്ടിയാണ് അമ്മയുടെ

ജീവിതം ഉരുകിത്തീരുന്നതെന്ന്

എന്നെങ്കിലും എൻ്റെ മക്കൾ മനസ്സിലാക്കുമോ? (Mathew, Diary, 07-07-2010)

എന്നിട്ടും അവളെ പഴിക്കുന്നവരുമുണ്ട്. എല്ലാമുപേക്ഷിച്ച് മറുനാട്ടിൽ വിലസിനടക്കാൻ പോയിക്കിടക്കുന്നതാണെന്ന് പറയുന്നവരുമുണ്ട്. (Despite this, there are people who blame her. That she has left everything to enjoy a life abroad) (Mathew, Diary; 16 May 2018; my translation.)

Tropes of self-sacrificing and long-suffering mothers are timeless and even stereotypical. But texts like Ancy’s diary entries and poems show us how mothers understood themselves and expressed themselves through these very tropes, and how they used it to articulate their personal circumstances. By staying on in the foreign country and fighting through loneliness, she sees herself as performing her motherly duties by protecting and providing for her children. It is not about the perfection of motherhood but the desire to show affection and care to those physically far away amidst accusations of indifference.

In a patriarchal society where women are expected to stay at home, women who leave their homes to become primary breadwinners are viewed with suspicion and blamed for being “selfish.” As excerpts from Ancy’s writings and my interviews with migrant women/mothers show, their narratives form around sacrifice, financial stability, and survival and reaffirmations of their loyalty to their culture and motherhood. This framing was more justifiable than a dream of ‘aspirational mobility’ for independence, work, or life. Certain social recognition was given to women who ‘remained in their culture’ despite the ‘tempting’ opportunities at ‘workspaces’. Their survival strategies were primarily a negotiation between making a living there and still remaining “cultural”.

Ancy’s narratives offer us just a glimpse into a vast experiential world shared by millions of migrant women. As part of my research on transnational Malayali women, I conduct in-depth interviews that reveal multiple aspects of their experiences, which are so familiar in that they have come up in conversations we have with them but so strange in that they are absent in academic and popular works on migration. The importance of archiving migrant women’s experiences is to understand the cultural norms and survival strategies they resorted to in making a new life. Each experience will be different–their accounts of the trauma of displacement, postpartum depression, workspace racism, and exposure to war are parts of their lives. With new communication technologies and social media platforms, expressions of the experiences of transnational migration have changed. But what the material I hold here reveals is that realities of migration cannot be limited to the experiences in the host country but are constantly in conversation with what and who they have left behind. This perspective in migration studies is absolutely crucial to understanding the realities of migrant mothers as they navigate through their gendered expectations of mothering and their sense of self. By putting across excerpts from a single pravasi mother’s writing, I am only treading the surface of a vast arena of literature that should be archived to document the life experiences of migrant women whose lived experience fluctuated between home and the foreign land.

Works Cited

- Gallo, Ester. 2005. “Unorthodox Sisters: Gender Relations and Generational Change among Malayali Migrants in Italy.” Indian Journal of Gender Studies 12 (2–3): 217–251. https://doi.org/10.1177/097152150501200204.

- George, Sheba Mariam. 2005. When Women Come First: Gender and Class in Transnational Migration. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Goel, Urmila. 2025. “The Absent.” Yearbook Migration and Society. https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/98003/1/9783839462935.pdf#page=110.

- Osella, Caroline, and Filippo Osella. 2008. Nuancing the Migrant Experience: Perspectives from Kerala, South India. London: SOAS. https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/5175/1/koshych_5_osellas.pdf.

About the Author: Aleena Maria Felix holds a postgraduate degree in Literary and Cultural Studies from the English and Foreign Languages University (EFLU) and completed her BA in English (Hons) at the University of Delhi. Her research explores migration, diaspora identity, and cultural syncretism, with a focus on Kerala’s transnational communities. She is currently compiling narratives and literature by Kerala’s migrant women, aiming to archive their experiences often marginalized in diasporic discourse.

Meaningful piece

Correct. A pravasy mother’s life is very painful.She sacrifice every thing for her children. Ancy is the best example.

മക്കളെ വിട്ട് ജോലിക്ക് പോകുമ്പോൾ അവരുടെ കരച്ചിൽ കാണുമ്പോൾ നെഞ്ചു നീറിയിട്ടുണ്ട്. തിരിച്ചു വരുന്നതുവരെ ആ നീറ്റൽ ഉണ്ടാവും.

പ്രവാസിയാകുന്ന അമ്മയുടെ വേദന എത്ര നാളുകൾ കഴിഞ്ഞാലാണ് ശമിക്കുക.

മനോഹരമായ, എന്നാൽ നീറുന്ന എഴുത്ത്

പുഴയിലേക്ക് എടുത്തു ചാടുന്ന എല്ലാവരും ഒരുപോലെ നീന്തി മറുകര കയറുകയില്ല…ചിലർ തുഴഞ്ഞുകൊണ്ടിരിക്കും……,ചിലർ വേഗത്തിൽ നീന്തും പക്ഷെ തിര അവരെ പുറകോട്ടു പിടിച്ചു തള്ളി കൊണ്ടേയിരിക്കും…ചിലർ ലക്ഷ്യം വിട്ട് പിന്നെയും പുറകോട്ടു തുഴഞ്ഞു അവിടെയും ഇവിടെയും ഇല്ലാത്ത ചുഴിയിൽ കിടന്നു കറങ്ങും.. കടന്നു പോകൽ എല്ലാവർക്കും ഒരു പോലെയല്ല.. വിരളമായി ചിലർ കരകാണുന്നു.

കര കാണത്തവരെ തേടി യാണ് യാത്ര എങ്കിൽ അവരുടെ അനുഭവങ്ങളിലേക്കാണ് യാത്ര എങ്കിൽ ,എഴുതാൻ താളുകൾ തികയാതെ വരും ….

“അറിയുന്നു നിന്നെ ഞാൻ നിഴലായി വെളിച്ചമായി

പിന്നെയോ നിലാവിൻ്റെ ഏറ്റ കുറച്ചിലായി”

Really good, congratulations dear for your efforts,I am also a pravassi mother,a friend of Ancy 😍

നന്നായി എഴുതി.👏🏻👏🏻👌🏻 മക്കളെ പിരിഞ്ഞു നീണ്ട അഞ്ചുവർഷക്കാലം ഒരമ്മ അനുഭവിച്ച വേദനയും ത്യാഗവും ആൻസിയുടെ വരികളിൽകൂടി മനസിലാക്കാൻ പറ്റി.കണ്ണു നിറച്ചു ആൻസിയുടെ വരികൾ. 💐💐💕💕

Absolutely touching story, as a migrant mother myself, I felt the emotions coming from Ancy’s life story. As a result of all the suffering and hard labour, God has showered his mercy upon all of our families.

This is indeed an insightful work.